Could You Kindly Snap It Up with the Meaning of Life?

Long before I met her, I knew Maira Kalman. I knew her from reading her books with my family. Our boys cracked up over the poetry in Sayonara, Mrs. Kackleman (1989): “Hey Hiroko, Are you loco? Would you like a cup of cocoa?” My husband loved the flap copy from Swami on Rye: Max in India (1995): “All is illusion but you must still pay $16.00 for this book,” with its “ageless and timeless, spiritually reinforced binding.” The insults on the final page—“for one million rupees I would not exchange turbans with you, and may onions grow out of your bellybutton”—enriched the family discourse. Kalman’s books passed that simple yet stringent test our boys gave their books: no laughs, no like.

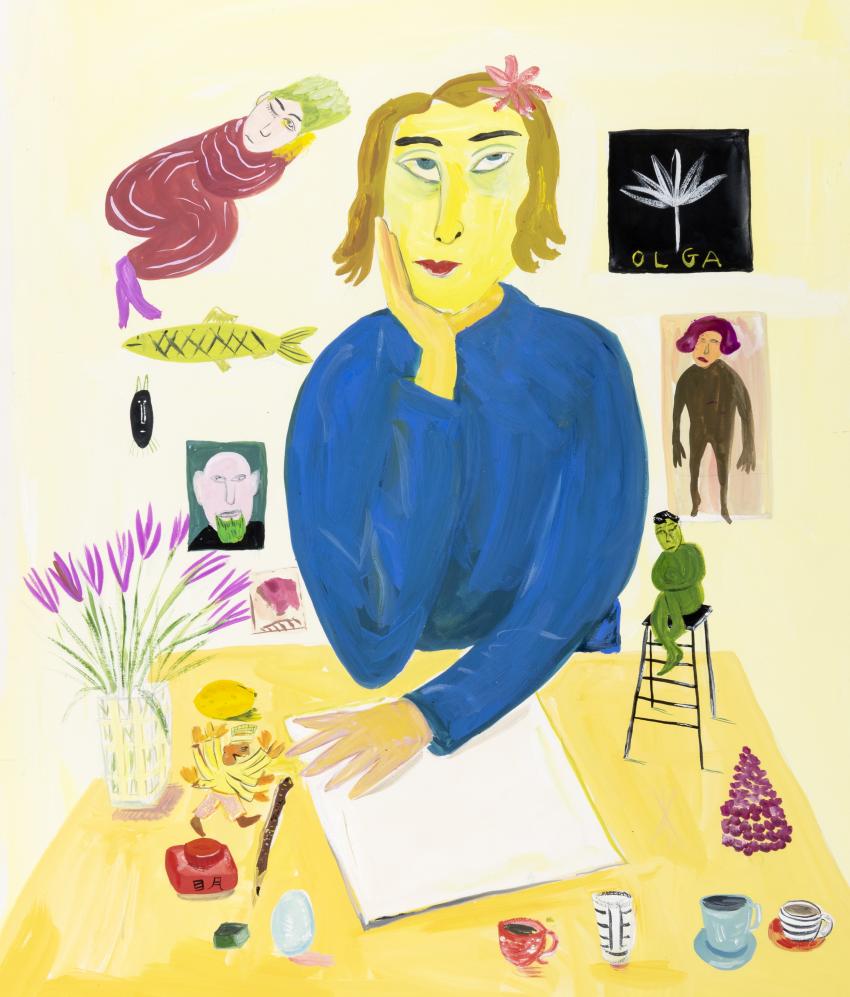

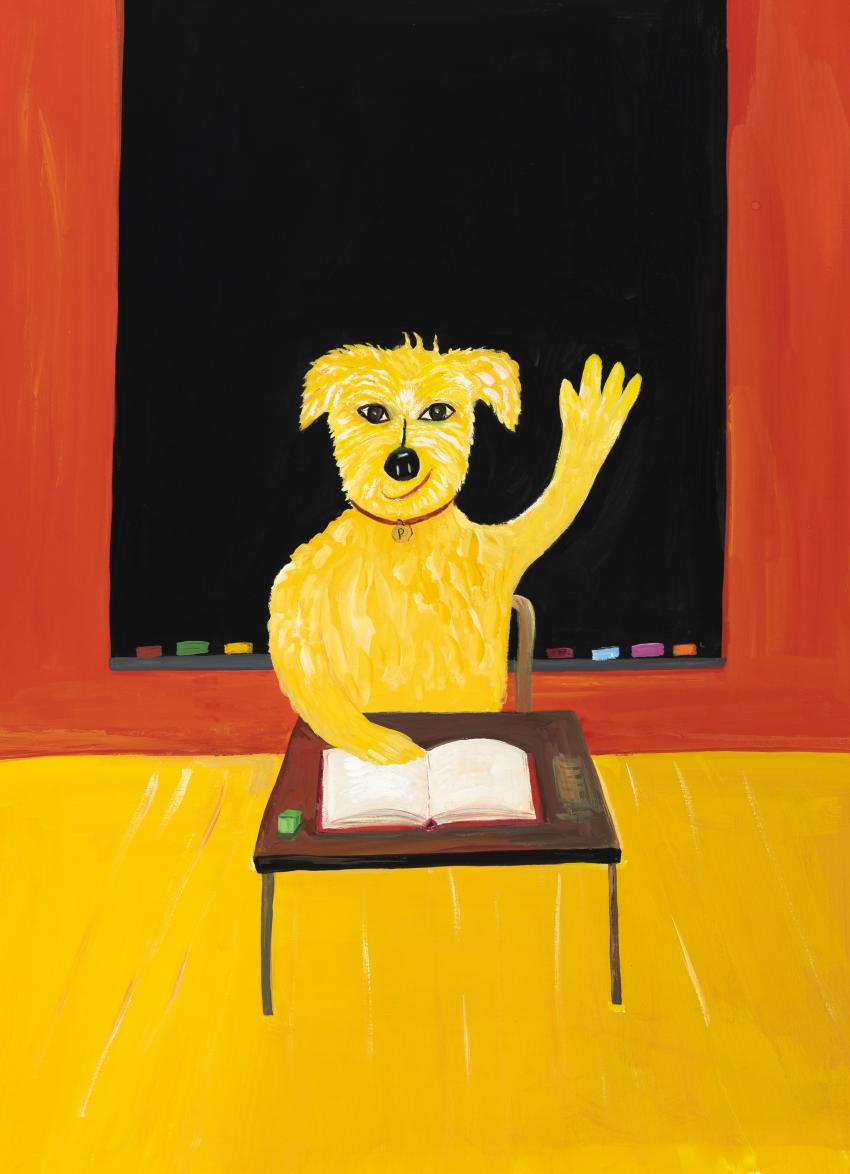

Maira Kalman, Illustration for Chicken Soup, Boots (Viking). Courtesy of Julie Saul Projects, New York. © 1993 Maira Kalman.

It is such a wonderful thing to meet a gifted illustrator or a talented writer. Kalman happens to be both. When I was introduced to her, it was no surprise to find she was just like her work: funny, smart, and an undisputed champion for the universal appeal of the picture book. Are they for children? Yes. Adults? You better believe it. Bring on the books with pictures. Her highly personal and somewhat eccentric worldview appeals to anyone who wants to be verbally and visually amused and challenged. Lewis Carroll’s Alice neatly sums up the essence of Kalman’s work with her famous question: “And what is the use of a book without pictures or conversations?”

Born in Tel Aviv, Israel, Kalman and her family moved to the Bronx in 1953. Much of her writing is grounded in this immigrant experience. Family stories from Russia and Israel, a honey cake recipe, her mother’s cosmopolitan wardrobe, even her Hungarian father-in-law’s carefully kept list of insults are folded into her expatriate narratives. A stack of suitcases in her living room attests to Kalman’s love of travel: coming and going are second nature to her. But there is a darker meaning here. “One of them belonged to a man who fled Danzig in 1939. As if I need reminders of the Holocaust. It’s all I think about,” Kalman writes.

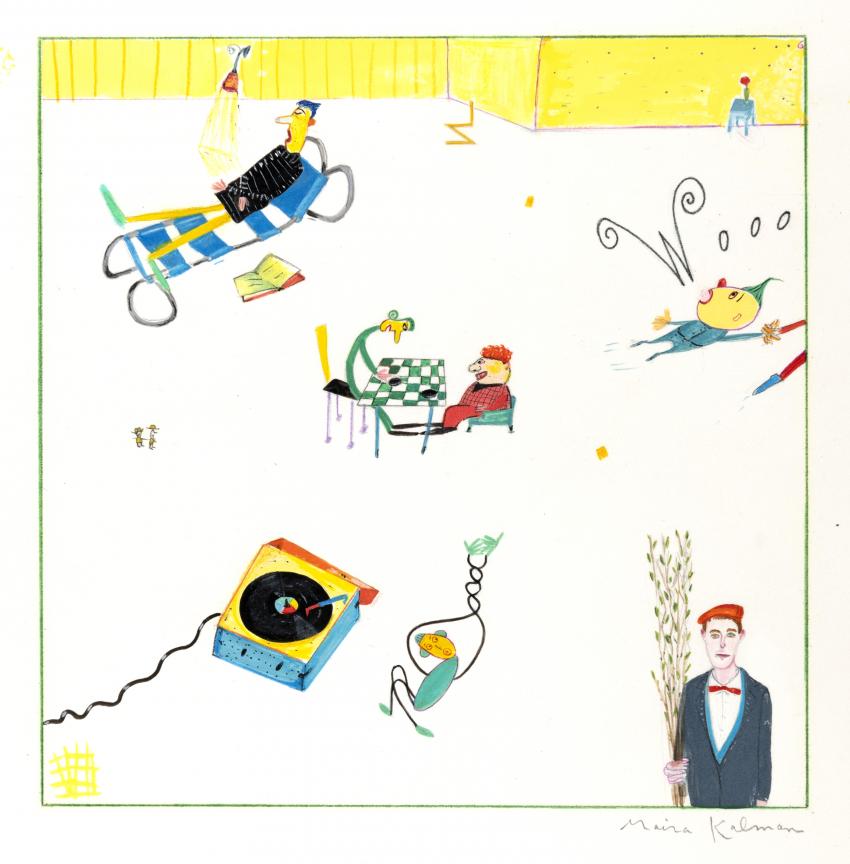

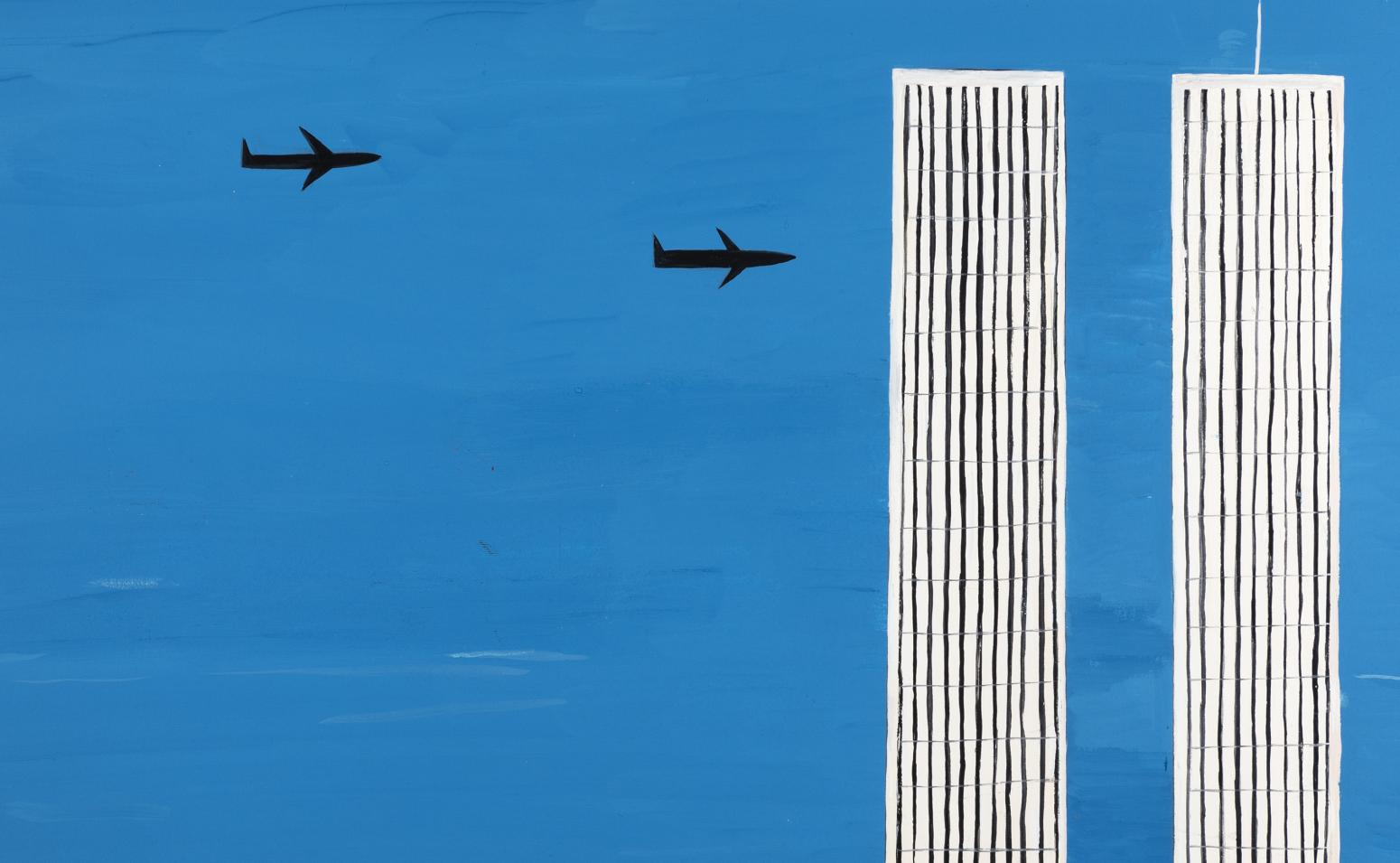

After graduating from the High School for Music and Art, she enrolled at New York University, where she met her future husband, designer Tibor Kalman. Her career in picture books began in 1986 when she illustrated a David Byrne song from the album Little Creatures. Since then, she has created 18 children’s books and a dozen more for adults, including the delightfully oddball illustrated version of The Elements of Style by William F. Strunk and E. B. White (2005). Let’s not forget her fifteen covers for The New Yorker, either, including the iconic post 9/11 “New Yorkistan” (2002) with Rick Meyerowitz. She is an indefatigable travel journalist who spent two years blogging for The New York Times. A magnet for creative talent, she has partnered with composers, dancers, musicians, and designers.

Illustration for Stay Up Late from a song by David Byrne. Courtesy of Julie Saul Projects, New York. © 1985 Maira Kalman.

Kalman has also had numerous museum exhibitions, most recently Sara Berman’s Closet in 2017, a show she organized with her son Alex at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. The year before, she won the American Institute of Graphic Arts medal “for storytelling, illustration and design, and for pushing the limits of all three.” What fuels all this creativity? Her motivation, she confesses, is “fear of death and snacks.” That might explain her extensive collection of candy bars with funny names like Cratch and Plopp. Like many artists, Kalman finds inspiration in what she loves. Her subject matter is the quotidian routines of her family (particularly her two children, Lulu and Alex, and more recently, her granddaughter, to whom she writes delightful illustrated letters). Her landscape is ever changing, and the hand that records what she sees is her own and unique.

Her first book, Stay Up Late, was a game-changer. It stood in ludic contrast to all those go-to-bed books filled with sleepy bunnies that litter children’s bookshelves. It was the anti-Good Night Moon, an anthem for kids who didn’t want to go to bed—and they were legion. Recounting this time in her life, Kalman wrote “I had two toddlers at this point and the divine inspired mayhem was the norm.” She described her second book, Hey Willy, See the Pyramids (1988): “The stories of my family. The random disconnect. Digressive. The beginning of walking down the street and noting. The three cross-eyed dogs. The boy with the boot on his head. All facts to report.” From the outset, Kalman has been a journalist whose chosen beat is to observe and record the absurd.

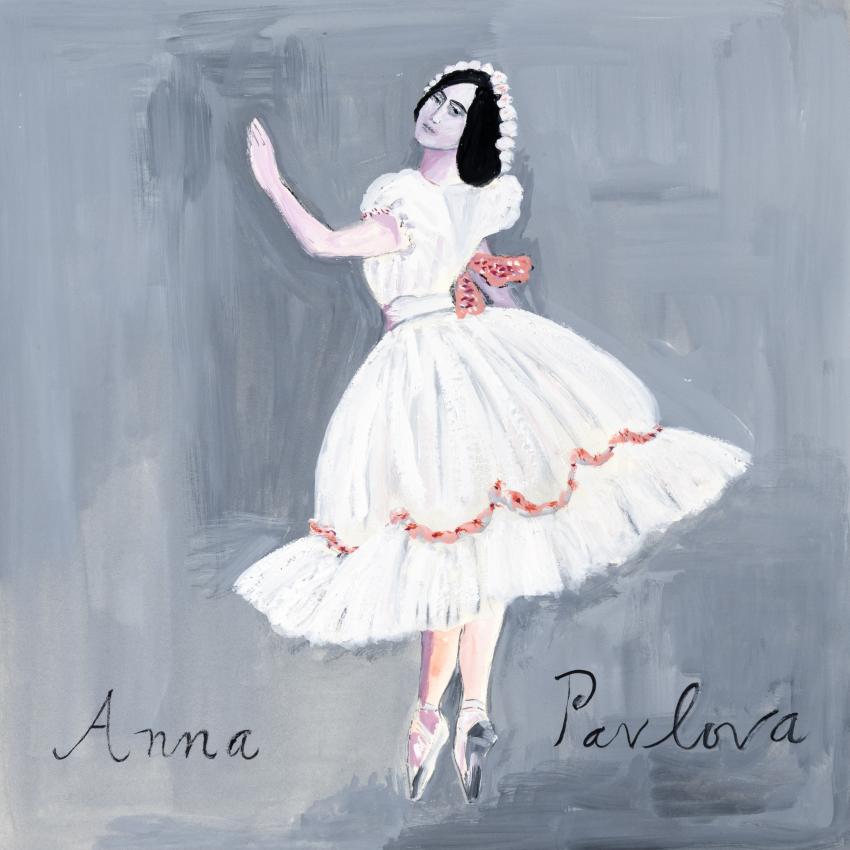

If Maurice Sendak gets credit for slipping Freud into the nursery, then Kalman can be seen as the picture book’s cultural choreographer, introducing a varied cast of her favorite icons, from Anna Pavlova (the dancer and the dessert) to Marcel Proust and Pepe le Pew. Some references may float over a kid’s head, but her older readers will smile. And who knows what might intrigue a child: what’s a smattering of Smetana? Where’s the Museum of Incredibly Modern Art? Can we go?

She has nothing but respect for the intelligence of her audience. “The best children’s books,” she says, “are as appealing to adults as they are to children. There has to be different levels of humor, different levels of reference, which allows a dialogue between adults and children. If you live with children, the kinds of conversations you have during the day range from the surreal to the mundane to the insane to the pedantic. And that language can be duplicated in writing, because the world is all of those things.”

Kalman has paid close attention to the history of the picture book. If her studio shelves are any guide, she is fond of the classics: here are Lewis Carroll, Roald Dahl, Kenneth Grahame, Edward Lear, A. A. Milne, Maurice Sendak, Dr. Seuss, and E. B. White. A stack of Eloise books attests to her appreciation of Kay Thompson’s punctuation-free voice. In a 1989 notebook Kalman wrote: “I can imagine Kay Thompson as she appeared in Funny Face—saying Darling—don’t you know those punctuation marks are too busy, too dreary, too fussy— Darling, they must absolutely go go go. But of course there was a rhythm and glow and pace created by that omission that leaves you breathless and delighted.” Kalman proves as acute a critic as she is a writer.

Then there is Ludwig Bemelmans. Kalman acknowledged him as inspiration in a letter she wrote: “Dear Ludwig. Dear L. B. You are the one I love the best. You were the role model. A bon vivant. A traveler. A lover of hotels and restaurants … Observing. Recording. Bringing an elegant and joyful approach to all the books and magazine articles. Humor. Panache. Joie de vivre. How many more French words do we need to describe you?” In detailing her delight in Bemelmans, Kalman neatly summarizes her own career as well.

Maira Kalman, Sketch of Max, n.d. Courtesy of Julie Saul Projects, New York. © Maira Kalman.

Closer to her own era is William Steig, an exemplar of the absurdist pen and a lover of beautiful words. Kalman’s poet Max Stravinsky bears more than a passing resemblance to Steig’s adventurer heroes Dominic the dog and that soulful artist mouse, Abelard Hassam de Chirico Flint. The witch-alligator’s advice to Dominic, to “take the road to the left, the road to adventure, and then give it everything you’ve got,” could be Max’s motto—or Kalman’s.

Since she was raised by a mother who was terrified of dogs, it seems unlikely that Kalman would have them on the brain, yet they appear in every one of her books. Even her alter ego is canine. The poet Max makes his debut in Hey Willy, See the Pyramids (1988), and is the hero of four further adventures, ranging the globe from New York and Hollywood to Paris and India. He is an artist, poet, traveler—a lover of life. Kalman writes about his genesis: “You know how these things happen. It was a hot day. An editor was waiting for a manuscript. And the character jumped onto the page. A bit of my husband, Tibor, but more than a bit of me. A wanderer, observing the absurd. Sometimes innocent and yearning. Sometimes downcast and confused. Well, isn’t that everybody. Max mirrored my life, the trips and funny distractions and observations. The essentialness of it all.”

In contrast, Kalman’s other canine hero, an Irish Wheaten Terrier named Pete, is all dog. Pete was the beloved family pet, a comforter during the dark period of her husband’s illness and death in 1999. Pete’s appetite was remarkable: he devoured a camera, shoes, glue, even rubber gloves. Kalman started keeping a list. Combined with her love of alphabets, this grew into the ABC book What Pete Ate (2001). In the sequel, Smartypants (Pete in School) (2003), Pete takes on the “gribbliest” teacher, Mr. Grompi Spitzer, and eats his pants. The pop quiz on the last page will delight anyone who ever had a dog eat their homework.

Current events provide Kalman with ideas, too: Next Stop, Grand Central evolved from a 1997 commission for six paintings that were reproduced, blown up in scale, and cut into banners that covered the scaffolding around Grand Central Terminal during its restoration. Just as children step through the pages of a book into another world, commuters could walk into a mirror world, Maira-landia. She has also painted large-scale city scenes in restaurants and, in 2009, she splashed a lively alphabet across the walls of Bronx PS 47’s library.

Fireboat (2002) addressed the heartbreak and heroism of 9/11 through the story of the John J. Harvey, a decommissioned fireboat whose crew (a group of Kalman’s friends who had bought the old boat for a lark) helped ferry survivors across the Hudson River to safety. Looking at Lincoln (2012) and Thomas Jefferson (2014) sprang from her fascination with history. Abraham Lincoln is one of Kalman’s great heroes, but we see her admiration tempered with humor in her invitation to a Sunday Social at the White House (tea and dainties offered by Mrs. Maira Lincoln).

Kalman believes that anything is up for discussion with kids. She paints the portrait of Thomas Jefferson and doesn’t varnish over the ethical and moral complexities his life presents. She writes: “Here is Jefferson’s farm book with a list of his slaves and the supplies they were given. Our hearts are broken.” The following page has a portrait of Sally Hemings with an explanation of what it means to pass as white. “To hide your background is a very sad thing. Perhaps people felt they had no choice in such a prejudiced land.”

Her most recent book, Bold and Brave (2018), with text by New York Senator Kirsten Gillibrand, shines light on the history of women’s rights in the United States. Chronicling heroines from Sojourner Truth to the Silent Sentinels, Kalman’s illustrations recall artist Charlotte Salomon’s words: “I became my mother, my grandmother. I learned to travel all their paths and became all of them … I knew I had a mission, and no power on earth could stop me.”

Kalman’s notebooks are both the incubators for her ideas and scrapbooks of her travels. Tucked between the pages are pressed leaves and flowers, postcards, tickets, coat checks, candy wrappers, and menus. There are lists, portraits, and layout sketches for books. A thought morphs into a double-page spread of titles and descriptive words. A paragraph grows into a seven-page story written while riding the subway. There are jokes: “Asked Siri - what is the meaning of life? Siri answered: ‘I can’t answer that right now, but let me write a very long play where nothing happens.’”

There are weeks, months, and years of notebooks. One picture falls out of a story, but slips back in two books later: the fish-eyed man originated in Hey, Willy (1988) but ended up in Ooh-la-la (Max in Love) (1994). There are several intriguing book titles that never made it: Max in Rome (alternate title, 100 Noodles); 25 Great Things I Have Seen Here and There; A Book about Shacks; Harebrained Schemes; Goofy Enterprises; The History of Shoes; The Book of Buckets and Boxes; and War Couture.

In her studio, photo files occupy an entire wall. Kalman is an inveterate collector of images, some her own, some from newspapers, books, and museums. What does she do with them all? She sees a photo of a performance artist cycling over the Brooklyn Bridge in a suit made of tin cans. Her interpretation appears in Chicken Soup, Boots (1993). A Cecil Beaton interior of an elegant drawing room becomes Max’s New York apartment in Max in Hollywood, Baby (1992).

She transforms a photo of Vladimir Nabokov as a boy into the portrait of Max in Swami on Rye. Over ten years later, she revisits the image, painting a version of it for The Principles of Uncertainty (2007). As Nabokov wrote, “For someone who knows how to look, everyday existence is as full of revelations and delights as it was to the eyes of the great poets of the past.” Revelations and delights: what better summary of the artist’s process?

Kalman has a deep and abiding affection for museums, but reverent she is not. In 2018 she collaborated with the Monica Bill Barnes Company, creating the Museum Workout, a two-mile exercise run set to Bee Gees songs at high decibels (with a voiceover narration by Kalman) through the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Two dancers in sequined dresses and sneakers faced off with Jean-Antoine Houdon’s bust of Benjamin Franklin and John Singer Sargent’s Madame X as they led their audience through deep-knee bends and stretches.

Then there is this playful list from a 1998 notebook: “Ten things to do in a museum besides look at art. Stop. Don’t you need a break? Aren’t you thirsty or hungry? Here are other things to do in a museum. 1. Have a snack. 2. Find a person wearing green shoes. 3. Find someone wearing a small hat. 4. Stare at the ceiling. 5. Find a cranky child (easy). 6. Stare into space. 7. Get an idea. 8. Stare at the floor.” Number nine is blank. There is no ten. But who’s counting? Swinging between existential angst and Borscht-Belt humor, Kalman finds a balance between the profound and the comical that appeals to child and grown up alike. In the words of her friend and co-author, Daniel Handler, she has “a soft spot for where suffering and sadness meet the ridiculous.” It is this quality that sets her work apart.

It is hard not to fall under the enchantment of Kalman’s worldview. Like Wilbur the Pig in E. B. White’s classic Charlotte’s Web, she marvels at the wonder, the tenderness of everything. Her philosophy: this is the place to be. Our job is to notice and appreciate it all. So why resist? As she says in her recent memoir, Cake (2018), “What have I learned? It is not a party without a cake. Bring on the cake. We really want to live.”