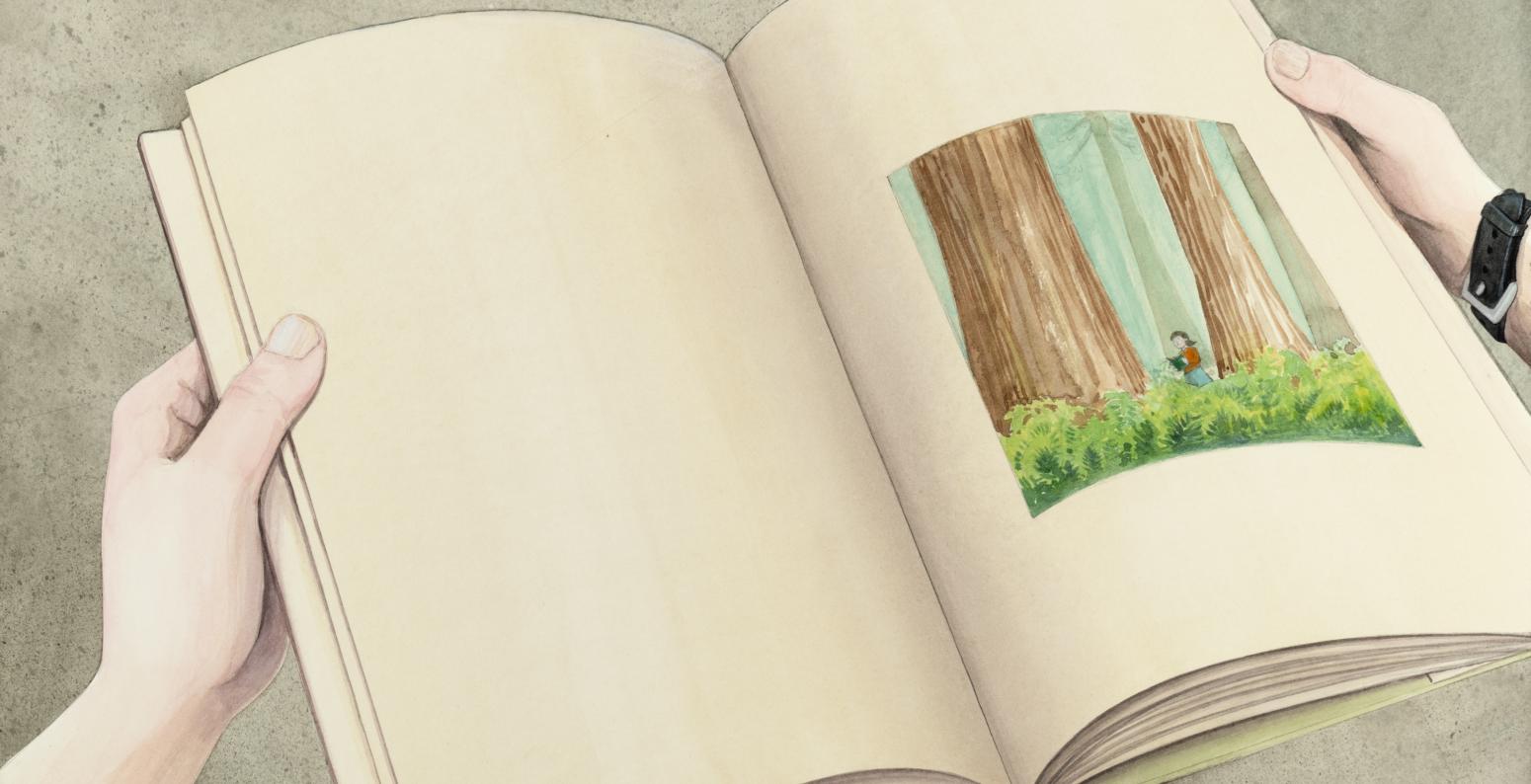

Jason Chin, Artwork for Redwoods (Square Fish). Collection of the artist. © 2009 Jason Chin.

Framing Pictures at Play

Have you ever been so immersed in a book that the whole world outside falls away? You’re so enmeshed that you forget that you’re even reading—until someone calls you for dinner and the spell is broken. Or perhaps there is something about the book itself that interrupts your absorption, something that makes you realize the book doesn’t just occupy your mind, it’s also a physical object you’re holding in your hands. Jason Chin’s title page for Redwoods (2009) is a perfect example. In a fleeting moment, the book makes you aware that you exist outside its paper walls. You recognize that you are the reader, and the book is a physical object, an imaginative artifact of someone else’s making. You’ve stepped out of the all-encompassing frame of the book and into a self-conscious state where reading—and thinking about reading—meet.

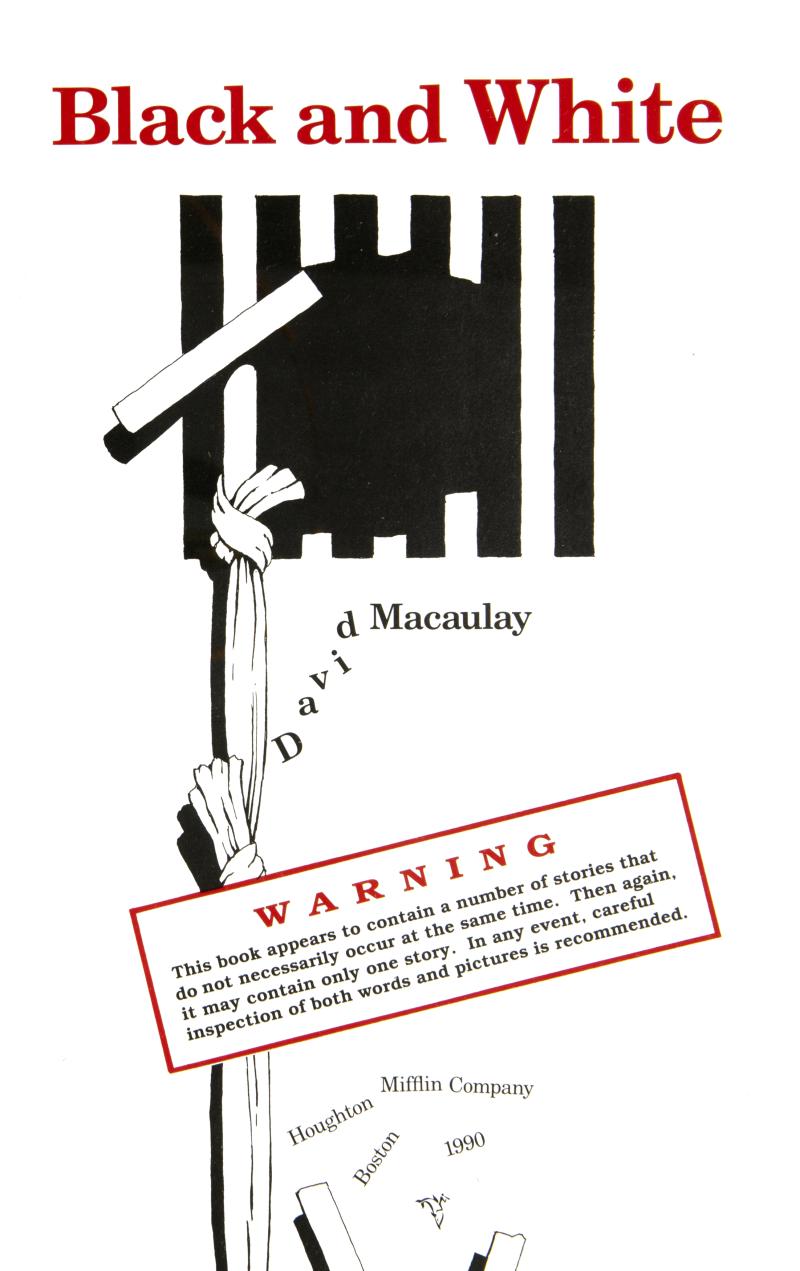

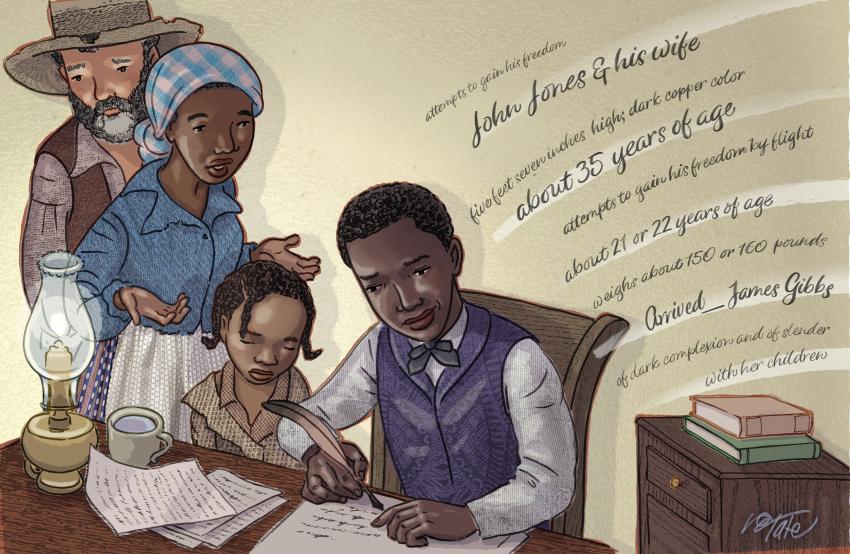

Don Tate, Artwork for William Still and His Freedom Stories: The Father of the Underground Railroad (Peachtree). Collection of the artist. © 2023 Don Tate.

Welcome! You have entered the lacuna of metafiction. Fear not, this is a space of freedom and playfulness. In its simplest terms, metafiction is “fiction about fiction—that is, fiction that includes within itself a commentary on its own narrative.” (Hutcheon 1). Metafictive picture books, then, are books that contain pictures about pictures and stories about stories. Through their art and writing, they summon you to think about story-telling and your role in story-making.

One of the earliest characters to appear in metafiction for young readers was Harold and his purple crayon. In 1955, Crockett Johnson crafted a seemingly straightforward story of a child expressing his imagination. It qualifies as metafiction because it’s a story about how a picture-story is created. Johnson illustrates how Harold uses the crayon to create the story world, to get himself out of a dangerous situation, and to draw his own happy ending.

Harold constructs a story with a beginning, climax, and conclusion that embeds within it another story following the same sequence.

Metafiction calls attention to the creative process. In Dan Santat’s Drawn Together (2018) by Minh Lê, a grandson and grandfather emerge from their awkward relationship when they discover their shared love of art. Here, their contemporary and traditional styles duel each other across the page. Yet, the grandfather’s brush crosses the gutter to protectively encircle his grandson, and their eyes meet as they “see each other for the first time.”

Dan Santat, Artwork for Drawn Together by Minh Lê by Minh Lê. Collection of the artist. © 2018 Dan Santat.

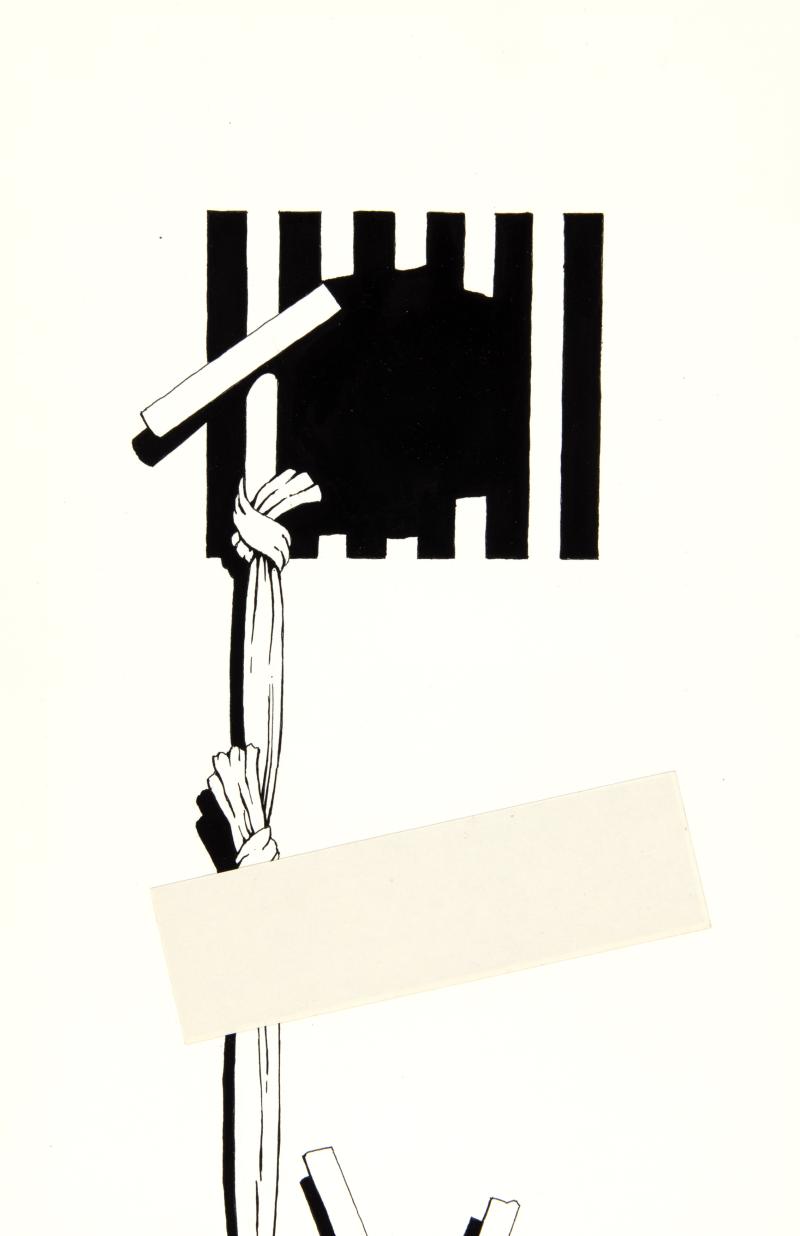

Metafiction also describes “fictional writing which self-consciously and systematically draws attention to itself as an artefact.” (Waugh 2). David Macaulay’s Black and White (1990) draws this kind of attention to itself as fictional and pictorial writing to great success—and for it, Macaulay won the Caldecott Medal.

The title page immediately invites you to consider the artificiality of the book and the book as an object. Not many books open with a warning that directs readers to give “careful inspection to both words and pictures.” The words describe your job as a reader and name how the book will complicate your reading. The author relinquishes control of the book and allows you to decide how to read and how to make story-sense of what you read.

Metafiction does not search for stability, but parties with endless possibility. Macaulay’s image offers no single meaning. Instead, the creator provides verbal and visual clues for you to put together and gives you the tools to put the pieces together anew every time you read.

An artist reveling in the experimental fields of metafiction, Macaulay exploits some of the properties that characterize the picture book form, such as the title page. Richard Byrne, too, teases the book’s materiality in This Book Just Ate My Dog (2014). The image exposes the book’s gutter as a dangerous place where illustrators can lose things—even their characters!

Richard Byrne, Artwork for This Book Just Ate My Dog (Henry Holt and Co.) Collection of Richard Byrne. © 2014 Richard Byrne.

Characters in metafictive picture books often behave differently than characters in other books. Sometimes they get lost in the book. Sometimes they invite you to join them, as in Julie Morstad’s cover illustration for Kyo Maclear’s It Began with a Page: How Gyo Fujikawa Drew the Way (2019). Morstad presents Fujikawa lifting a blank jacket to invite the reader into the colorful interior pages of a book and says “it began with a page.”

Julie Morstad, Artwork for It Began with a Page. Collection of the artist. © 2019 Julie Morstad.

Intertextuality—or texts (books, words, and pictures) that refer to other texts (books, words, and pictures)—enjoys a unique place in the entertainment offered by metafiction. Familiar characters might appear in new ways. Early in Journey (2013), Aaron Becker shows the back of a child holding a purple crayon. Immediately, readers think of Harold. But Becker switches things up when he introduces a different child wielding a red crayon to shape her own adventures.

Aaron Becker, Artwork for Journey (Candlewick). Collection of the artist. © 2013 Aaron Becker.

We know that characters don’t usually cross into each other’s books nor read about themselves in a book in which they appear, but in metafiction both things might happen. An intertextual reference to a familiar story might serve an ironic purpose as it does in David Elliott’s Baabwaa and Wooliam (2017) illustrated by Melissa Sweet. We certainly recognize that wolves and sheep don’t have cozy conversations. But when they do, we delight in the absurdity and laugh out loud, even if we worry a little about those two sheep. After all, even in metafiction, a wolf in sheep’s clothing surely cannot be trusted.

Melissa Sweet, Artwork for Baabwaa and Wooliam: A Tale of Literacy, Dental Hygiene, and Friendship by David Elliott (Candlewick). Collection of the artist. © 2021 Melissa Sweet.

Intertextuality often invokes canonical texts. In Bats in the Library (2008), Brian Lies submits a reverential frolic through classic children’s literature. Characters from well-known stories have grown bat wings. As we recognize Little Red Riding Hood and Winnie-the-Pooh, represented in batty garb, we’re amused at the clever logic. Of course, nocturnal bats in a library would have plenty of time to know all these books! The illustrations also exemplify how reading a story can take hold of one so strongly that, like the bats, readers become the characters and act out their story roles.

Brian Lies, Artwork for Bats at the Library (A Bat Book) (Clarion). Collection of the artist. © 2014 Brian Lies.

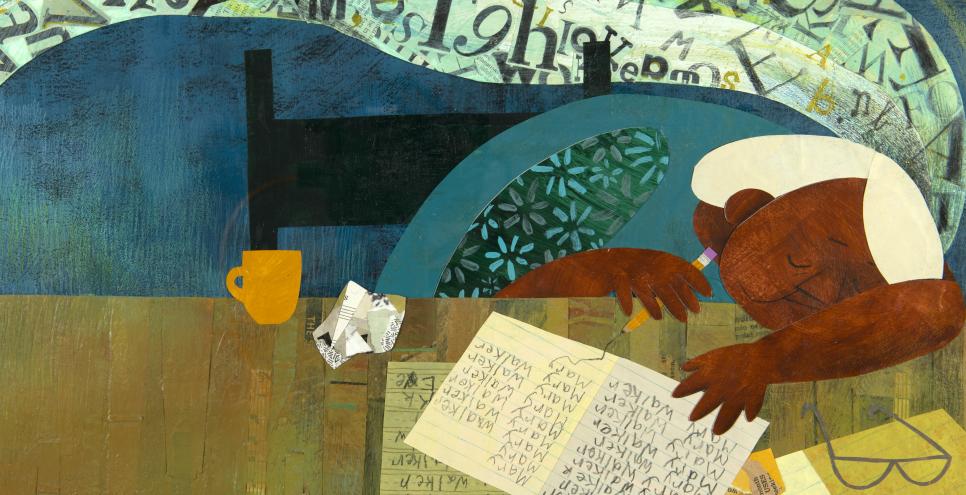

Intertextuality also reshapes the canon by centering stories, writers, and illustrators historically omitted. In Dreamers (2018), Yuyi Morales depicts the mammoth work of making books for a young reader. She visually quotes pages from books by other artists and replicates their titles and covers. The women wields a needle and thread to bind together new stories still being told and even the stories her child will write with a larger-than-life pencil.

Yuyi Morales, Artwork for Dreamers (Neal Porter Books). Collection of the artist. © 2018 Yuyi Morales.

It’s fun to identify the picture books within the picture book Morales illustrates. Nesting pictures is a favorite technique of metafiction creators. Pictures about pictures within pictures can leave us shaking our heads as we look and look ever deeper into the picture space. In Here and Now (2019) by Julie Denos, illustrator E. B. Goodale depicts a woman who holds a book that replicates the picture of a woman holding a picture of herself in a book that contains yet another picture of the same woman holding a book in which a woman holds a picture of a woman holding a book with a picture of herself. We keep looking, wondering, asking how far we can see and if this nesting continues in perpetuity. Metafiction creators love the idea of infinity—infinite ways of reading, infinite meanings of a single book, infinite creativity for author, illustrator, and reader.

E. B. Goodale, Artwork for Here and Now by Julia Denos. Collection of the Artist. © 2019 E. B. Goodale.

Though words like metafiction and intertextuality sound heady, it’s important to remember that metafiction asks only for your willingness to play with what you see and what you think a book or a picture means. Metafiction asks you to play with the book, interact with it as an object: turn the book from horizontal to vertical in Christian Robinson’s Another, touch soft fur in Dorothy Kunhardt’s Pat the Bunny, or move pieces in Paul Zelinsky’s Wheels on the Bus. Enjoy what David Macaulay calls the “literary recreation” (Black and White CIP) of metafiction. Celebrate the picture book and discover yourself as a co-creating reader.

Critical Works Cited

Hutcheon, Linda. Narcisstic Narrative: The Metafictional Paradox. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1980.

Waugh, Patricia. Metafiction: The Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious. Methuen, 1984.

Picturebooks Cited

Becker, Aaron. Journey. Candlewick, 2013.

Byrne, Richard. The Book Just Ate My Dog. Holt, 2014.

Chin, Jason, Redwoods, Square Fish, 2009.

Denos, Julie. Here and Now. Illustrated by E. B. Goodale. Candlewick, 2019.

Elliott, David. Baabwaa and Wooliam: A Tale of Literacy, Dental Hygiene, and Friendship, Illustrated by Melissa Sweet. Candlewick, 2017.

Harrison, Vashti. Big. Little Brown, 2023.

Johnson, Crockett. Harold and the Purple Crayon. Harper, 1955.

Kunhardt, Dorothy. Pat the Bunny. Golden Books, 1940.

Lê, Minh. Drawn Together. Illustrated by Dan Santat. Little Brown, 2018.

Lies, Brian. Bats in the Library. Clarion, 2008.

Macaulay, David. Black and White. Houghton Mifflin, 1990.

Morales, Yuyi. Dreamers. Neal Porter Books, 2018.

Robinson, Christian. Another. Atheneum, 2019.

Tate, Don. William Still and His Freedom Stories: The Father of the Underground Railroad. Peachtree, 2020.

Zelinsky, Paul O. Wheels on the Bus. Penguin Random House, 1990.