Speechless: The Art of Wordless Picture Books

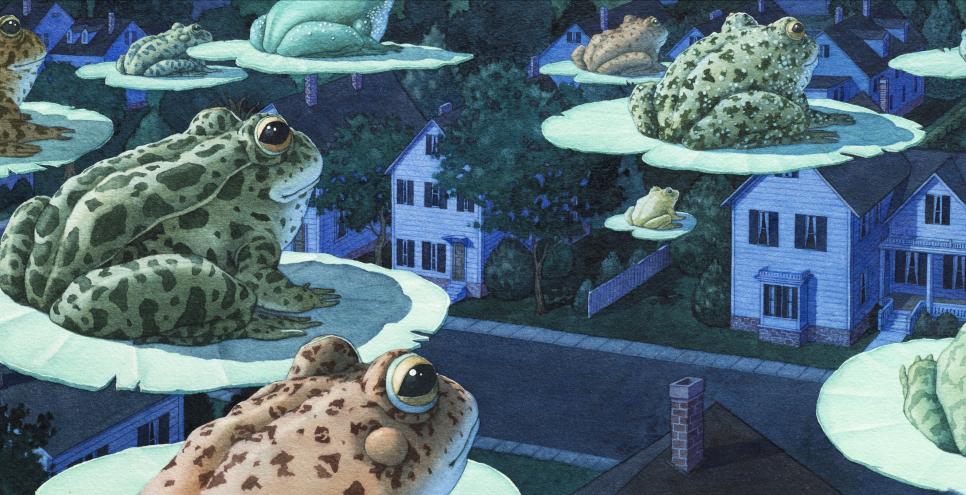

A lost clown is befriended by a farmer. A frightened mouse is spared by a hungry lion. A beloved dog’s ball is destroyed and replaced. These stories come alive in picture books rich in color and strong in narrative—and all without words. Wordless picture books take center stage in The Carle’s new exhibition Speechless: The Art of Wordless Picture Books, on view July 17 through December 5, 2021. Artist and author David Wiesner, who has won six Caldecott citations, five of which were awarded for his tour-de-force wordless picture books, has traded in his paints and brushes to curate the exhibition.

Wiesner celebrates masters of the craft, including some of the artists who influenced his own remarkable career. He presents a 90-year history of graphic storytelling and examines how the wordless genre for children developed over time. The exhibition traces the form’s emergence from the shadows of mainstream publishing to its enthusiastic embrace by the public today.

A Word about Wordless Picture Books

A book without text seems like a very strange thing. How do you even read it? You read the pictures! “A character can’t say, ‘I’m happy’ or ‘I’m sad,’” says Wiesner. “The images must show that and everything else the character may be thinking or feeling. Emotion is also shown through the context of the pictures: lighting creates mood while the size of an image effects how the reader responds to a character, as does the size of the character within the image.”

For artists, the absence of text means unfettered access to every inch of the page without needing to leave space for blocks of text or word balloons. This gives artists the ability to illustrate the pages in any way they want. They can divide spreads into multiple images and use borders and other design elements freely, all without the otherwise ever-present worry of, “Where will I put the text?” This freedom has fostered a long history of beautiful and ground-breaking publications, including the 22 books featured in the exhibition.

The first wordless picture book for children published in the United States was Ruth Carroll’s What Whiskers Did (1932). Drawn in charcoal crayon, it tells the story of a Scottish terrier who befriends a family of rabbits. Carroll contained her images within hand-drawn panels, although the story characters often break free of those borders in their energetic activities.

Remarkably, not another wordless picture book was published in America for thirty years. It came in 1962 with Tomi Ungerer’s Snail, Where Are You?, a conceptually simple and elegant book in which Ungerer asks readers to look closely at the pictures, and at the world around them. Like Ungerer, Tana Hoban’s Circles, Triangles, and Squares (1974) invites readers to look anew at the geometry of ordinary things. Hoban was one of the few photographers working in picture books in the 1970s. Her numerous wordless books were simple in presentation, yet sophisticated in concept.

Lynd Ward was a pioneer of wordless books. In the late 1920’s and early 1930’s he created a series of wordless novels for adults. He also had a long career as a children’s book illustrator, although he made only a single wordless book for children, The Silver Pony (1973). It tells the epic story of a farm boy who encounters a magical winged pony. Ward painted the illustrations in shimmering shades of grey and black.

Innovative Design and Storytelling

Numerous artists have taken the wordless genre and expanded its definition in innovative ways. Molly Bang’s The Grey Lady and the Strawberry Snatcher (1980) is visually unlike any other book, ingeniously playing with positive and negative space. In Wave (2008), Suzy Lee uses the “gutter” of the book as the border between reality and fantasy. Molly Idle’s Flora and the Flamingo (2013) is a “moveable” book that uses flaps as a form of animation.

Artists also use panels to take book design to new heights. In Shaun Tan’s The Arrival, the artist divides his pages into panels ranging from three to as many as 60 images! With so many panels, Tan shows character emotions in great detail. Chris Raschka often shows his protagonist multiple times per page to indicate sequential movement in A Ball for Daisy (2011). Other times he portrays Daisy in single, page-filling close-ups to emphasize her emotions, both happy and sad. Peter Spier’s Rain (1982) is a simple story—two children go outside and play in the rain—yet his page designs create an exciting reading experience. Spier’s pictures continually shift from single-image pages and double-page spreads to pages divided into panels of different sizes.

Travel across Time and Space

Travel can be literal or imaginary. In Truck (1980), Donald Crews’ geometric, hard-edged drawings and flat colors are in perfect sync with the large vehicles they portray. Crews takes his truck—and readers—through a cityscape and across the countryside. The pictures practically jump (or drive) off the page.

Istvan Banyai’s Zoom (1995) brings readers on a mind-bending trip around the world. As they turn the pages, readers quickly discover that each illustration is a small section of a larger image revealed on the following page. Perspectives shift with every turn.

Dinosaurs are the ancestors of birds, and Eric Rohmann uses a small bird to transport readers to a prehistoric era in Time Flies (1994). Rohmann’s borders around the first illustrations disappear as museum skeletons transform into giant dinosaurs. The borders reappear at the end when the bird returns readers to the present day. Raúl Colón changes his style in Draw! (2014) as the story moves from reality to fantasy. He paints in thin, flat watercolor washes when depicting a boy in his room, but when the boy enters his own drawing, Colón switches to vibrant colored pencils.

The Red Book (2004) is the first title in Barbara Lehman’s ongoing exploration of wordless storytelling. It tells the fantastical story of two children who connect across time and space.

In Another (2019), Christian Robinson transports readers into a girl’s dream world and back out again. The girl and her cat enter an alternate world that contains doubles of everything and everyone. Robinson creates an impossible space in which characters walk right side up and upside-down.

It’s All in the Expression

Emily Arnold McCully, in her wordless picture book Picnic (1984), illustrates her mice characters with a wide range of emotions. When the littlest mouse is lost, McCully isolates the figure amid the tall weeds. Readers sense its fear at being alone, as well as its joy at finding food and later being rescued. Another mouse features prominently in Jerry Pinkney’s The Lion and the Mouse (2009), in which the artist uses his remarkable skills as storyteller, designer, draftsman, and painter to update an ancient fable. Creating distinct animal personalities is one of Pinkney’s greatest talents. Here his characters—one huge, one tiny—are full of emotion. The lion in particular shows an amazing range of facial expressions, including on the book’s striking—and wordless—cover illustration.

Peter Sís’s An Ocean World (1992) is a story about a whale searching for its place in a vast ocean. Sís echoes the shape of the whale to show how it relates to both the natural and man-made worlds. Although the whale is an enormous creature, Sís emphasizes its loneliness by keeping its size small within the picture frame. Likewise, Issa Watanabe focuses on animals in her book Migrants (2020). Watanabe’s illustrations read more as a poem than a story. While the animals struggle through great hardship, they never stop caring for each other.

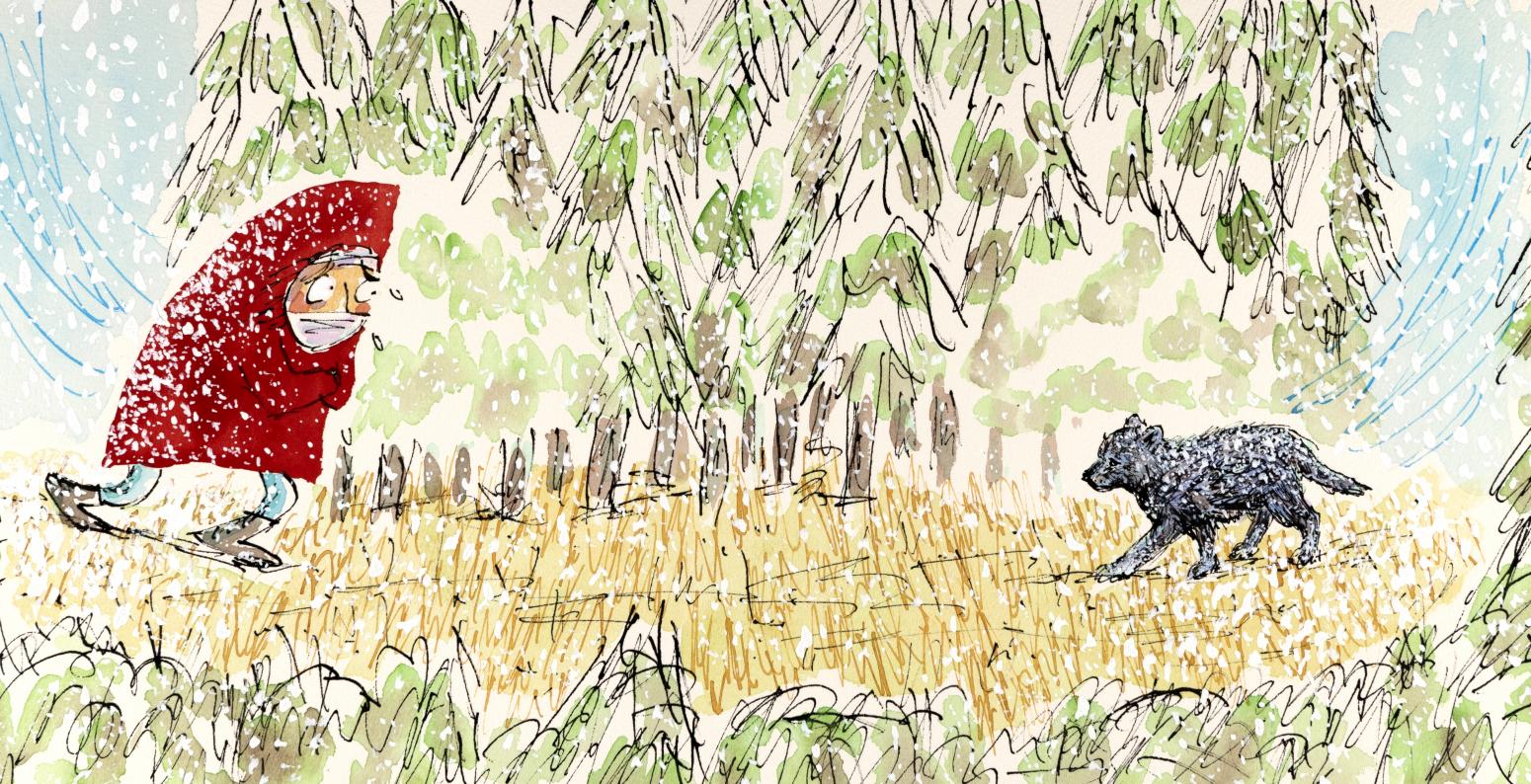

Marla Frazee sets The Farmer and the Clown (2014) in a barren landscape of ochre, brown, and gray earth tones. A circus train passes in the distance and a little clown falls off. The clown’s bright red suit stands out against the muted surroundings. Frazee uses red again for the farmer’s long johns, visually connecting the two characters as their bond begins to grow. Matthew Cordell conveys emotion by varying the sizes of his characters on the page in Wolf in the Snow (2017). Initially a child and wolf pup appear small against large snowy fields to indicate their vulnerable predicaments. When the child and pup finally meet, Cordell centers each one large on the page and removes the background so readers focus only on their expressions.

Awards Galore

The art in wordless picture books has not gone unnoticed. Peter Spier’s Noah’s Ark was the first wordless book to receive the prestigious Caldecott Medal. Since then, five other wordless books have won the Caldecott: Tuesday (1991) and Flotsam (2006) by David Wiesner; The Lion and the Mouse (2009) by Jerry Pinkney; A Ball for Daisy (2011) by Chris Raschka; and Wolf in the Snow (2017) by Matthew Cordell. The first two wordless books awarded Caldecott Honors were published in the same year, 1980: Molly Bang’s The Grey Lady and the Strawberry Snatcher and Truck by Donald Crews. Eight other wordless books have since been designated Caldecott Honors, including three in the exhibition: Time Flies (1994), The Red Book (2004), and Flora and the Flamingo (2013).

Books for Everyone

Wordless books are universal; they can be read by children and adults and people of all languages. Yet their pictures are open to interpretation and every person reads a wordless book in their own way. Creators of wordless books invite readers to become partners in the storytelling process—an empowering request. “What we see in this exhibition is how wordless picture books have inspired artists to create remarkable visual reading experiences,” says Wiesner. “By making the decision to remove their voice—the words—these artists pare their books to the essence of their art—the pictures—leaving those pictures open to interpretation. In doing so, the artists invite children to make those stories their own.”

Exhibition Booklist

What Whiskers Did (1932) by Ruth Carroll

Snail, Where are You? (1962) by Tomi Ungerer

The Silver Pony (1973) by Lynd Ward

Circles, Triangles, Squares (1974) by Tana Hoban

The Grey Lady and the Strawberry Snatcher (1980) by Molly Bang

Truck (1980) by Donald Crews

Rain (1982) by Peter Spier

Picnic (1984) by Emily Arnold McCully

An Ocean World (1992) by Peter Sis

Time Flies (1994) by Eric Rohmann

Zoom (1995) by Istvan Banyai

The Red Book (2004) by Barbara Lehman

The Arrival (2006) by Shaun Tan

Wave (2008) by Suzy Lee

The Lion and the Mouse (2009) by Jerry Pinkney

A Ball for Daisy (2011) by Chris Raschka

Flora and the Flamingo (2013) by Molly Idle

Draw! (2014) by Raúl Colón

The Farmer and the Clown (2014) by Marla Frazee

Wolf in the Snow (2017) by Matthew Cordell

Another (2019) by Christian Robinson

Migrants (2020) by Issa Watanabe

Programming

Special Members’ Gallery Tour with Guest Curator David Wiesner

July 18, 2021

10:00 am and 11:00 am

Free for members

Register here

Join guest curator and award-winning artist David Wiesner for a guided tour of Speechless: The Art of Wordless Picture Books. Space is very limited.

Online Program with Simmons University

2021 Mary Nagel Sweetser Lecture with David Wiesner

“Artist & Reader: Partners in Storytelling”

July 22, 2021

7:00 pm

Register here

Everyday Art Project: Shape Your Story

August 12 – September 19, 2021

Inspired by the exhibition Speechless: The Art of Wordless Picture Books, experiment with shapes and watercolor pencils to start your own stories.

About the Curator

David Wiesner is one of the best-loved and most highly acclaimed picture book creators in the world. His books have been translated into more than a dozen languages and have won numerous awards in the United States and abroad. Three of the picture books he both wrote and illustrated became instant classics when they won the prestigious Caldecott Medal: Tuesday in 1992, The Three Pigs in 2002, and Flotsam in 2007, making him only the second person in the award’s long history to have won three times. He has also received three Caldecott Honors, for Free Fall, Sector 7, and Mr. Wuffles!

Wiesner grew up in suburban New Jersey and was known to his classmates as “the kid who could draw.” He studied at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he committed himself to the full-time study of art and to explore further his passion for visual storytelling. He soon discovered that picture books were the perfect vehicle for his work.

Wiesner generally spends several years creating each new book. Many versions are sketched and revised until the story line flows smoothly and each image works the way he wants it to. He creates three-dimensional models of objects he can’t observe in real life, such as flying pigs and lizards standing upright, to add authenticity to his drawings.

Wiesner lives with his family outside Philadelphia.

About the Museum

The mission of The Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art, a non-profit organization in Amherst, MA, is to inspire a love of art and reading through picture books. A leading advocate in its field, The Carle collects, preserves, presents, and celebrates picture books and picture book illustrations from around the world. In addition to underscoring the cultural, historical, and artistic significance of picture books and their art form, The Carle offers educational programs that provide a foundation for arts integration and literacy.

The late Eric and Barbara Carle co-founded the Museum in November 2002. Carle was the renowned author and illustrator of more than 70 books, including the 1969 classic The Very Hungry Caterpillar. Since opening, the 43,000-square foot facility has served more than 750,000 visitors, including 50,000 schoolchildren. The Carle houses more than 11,000 objects, including 7,300 permanent collection illustrations. The Carle has three art galleries, an art studio, a theater, picture book and scholarly libraries, and educational programs for families, scholars, educators, and schoolchildren. Bobbie’s Meadow is an outdoor space that combines art and nature. Educational offerings include professional training for educators around the country and Master’s degree programs in children’s literature with Simmons University.

The Museum offers digital resources, including art activities, book recommendations, collections videos, and professional development and workshops for online visitors. Learn more at www.carlemuseum.org and on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram @CarleMuseum.

For media inquiries, additional press information, and photo requests, please contact Sandy Soderberg at sandys@carlemuseum.org.