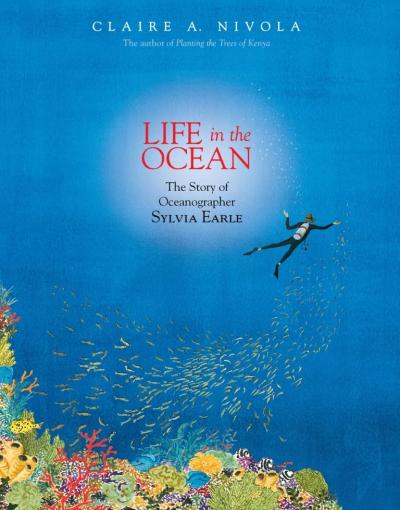

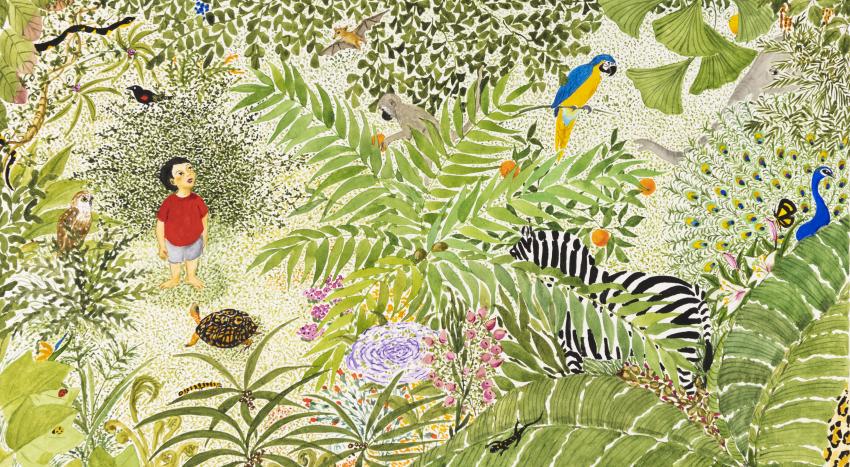

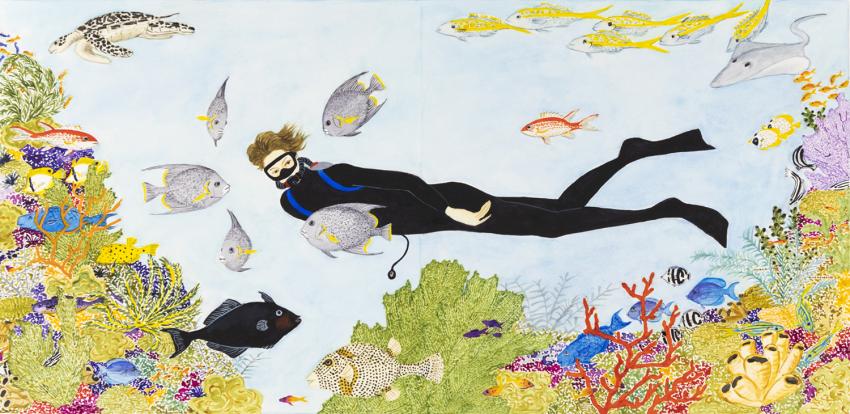

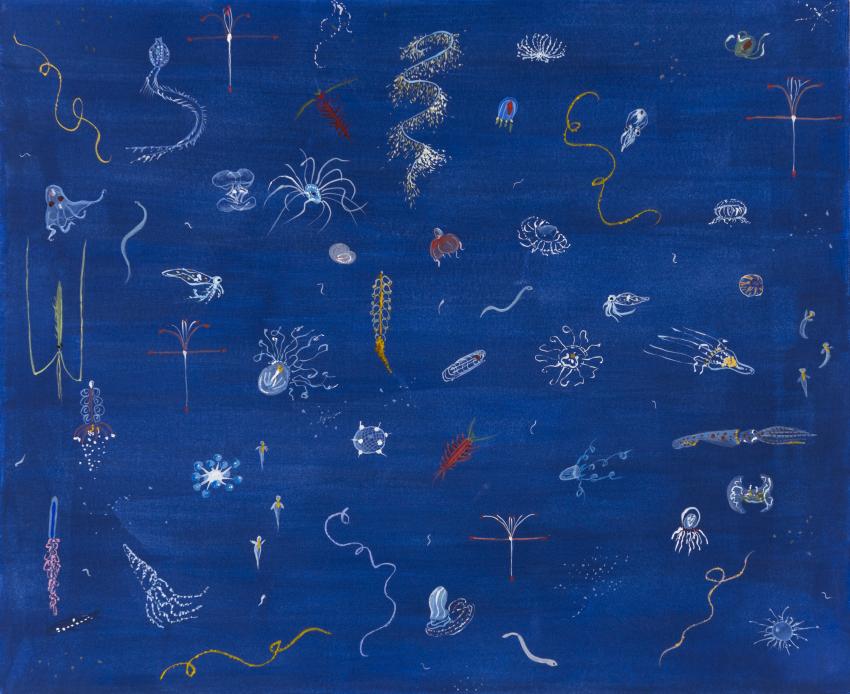

Claire A. Nivola, Illustration for Life in the Ocean: The Story of Oceanographer Sylvia Earle (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). Collection of the artist. © 2012 Claire A. Nivola.

The Art of Claire A. Nivola: From the Personal to the Prominent

The daughter of artists, Claire Nivola drew incessantly as a child and developed exceptional skill without the academic regimen of art school. Fresh out of college, Nivola inherited a book project from her father who deflected a publishing offer from the esteemed editor Fabio Coen at Pantheon. Tasked with creating illustrations for Disobedient Eels and Other Italian Tales (1970), its resulting publication encouraged Nivola to pursue this career path. Her drawings comprised an energetic, nervous draftsmanship overlaid with delicate washes of color suggestive of the French artist Raoul Dufy and—perhaps closer to home—Ludwig Bemelmans, the creator of Madeline. Subsequently, Nivola was stymied by rejection, receiving only two more commissions during the decade—one of which was a collaboration with her mother Ruth titled The Messy Rabbit (1978), a cautionary tale about personal responsibility. For her third book—the ecologically concerned Save the Earth (1978)—Nivola worked with editor Frances Foster. This collaboration would resuscitate Nivola’s career in the profession almost 20 years later, as Foster became legendary in the field of children’s literature.

Nivola pursued painting, graphic design, and mural painting. She married and had her first child in 1983. In 1992, after an extended hiatus to raise her family, she made a rare exception and accepted a commission to create 53 bas-relief panels recounting the shifting human relationship to the Tennessee River for the Chattanooga Aquarium. She worked on the panels after her children went to bed, and they often commented on the works before being shipped out. Two years later, serendipity re-connected Nivola with Foster when an illustrator withdrew from a project: Betty Jean Lifton’s Tell Me a Real Adoption Story (1994). This opportunity led to a collaboration of eight books over the next two decades.

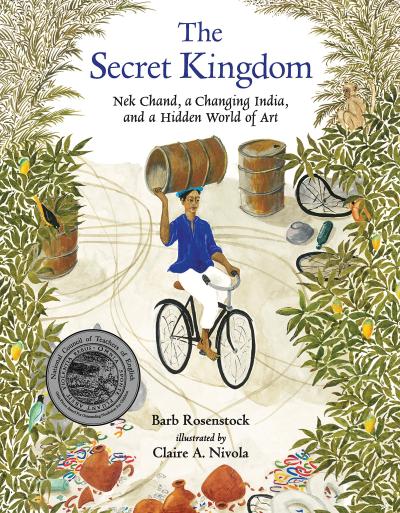

Nivola’s subjects range from the intensely personal—her parents and family—to illustrating the lives of such prominent women as poet Emily Dickinson (albeit in charmingly fictional form), author Emma Lazarus, oceanographer Sylvia Earle, and activist Wangari Maathai. Her books have played an important role in articulating the achievements of women. A rare consideration of men appears in The Secret Kingdom: Nek Chand, a Changing India, and a Hidden World of Art (2018), by Barbara Rosenstock. Nivola’s own longtime admiration of India’s vibrant colors and tradition of miniature painting and her husband’s interest in the culture and religions of India inspired her to accept the project. She appreciated the connection to the planned city of Chandigarh, the joint capital of the northern Indian states of Punjab and Haryana. The prominent French 20th-century architect Le Corbusier, who was a friend of and powerful influence on Nivola’s father, Costantino, had designed this ambitious undertaking. The ensuing essay considers Nivola’s career through the lens of three books with a personal connection, two based in fiction, and five that are biographical.

In the wake of her reunion with Foster, Nivola wrote her about an idea for a book based on the story of her mother’s escape from Nazi Germany,1 which developed into the 1997 picture book Elisabeth. In an undated six-page letter, (written at Nivola’s request, which then became the basis for the book) her mother Ruth recounts her escape from Berlin, forced to leave everything behind, including her beloved doll, Elisabeth.2 In 1953, when she was turning six, Claire asked her mother for a doll. Ruth, like her husband, maintained very high standards and eschewed any mass-market mediocrity; consequently, she scoured the antique shops in East Hampton, Long Island where they lived, and were, coincidentally, neighbors and friends of the de Koonings (Willem and Elaine) and Pollocks (Jackson and Lee Krasner). In one of the shops, a familiar “vintage” doll caught Ruth’s eye, and, upon inspection, she noticed the right forearm had two puncture marks in the very same spot where her dog Fifi had bitten Elisabeth years ago. She purchased the doll and gave it to her daughter, who subsequently handed it down to her daughter, and it remains in the family to this day. While the odds are extraordinary, the evidence is persuasive that this doll is one and the same. This personal narrative anticipated by two years Tomi Ungerer’s equally implausible account of poignant serendipity, Otto: The Autobiography of a Teddy Bear (1999). Through the eyes of a beloved teddy bear, Ungerer provides a heart-wrenching account of the devastation of the Holocaust tempered by the reunion in America of two childhood friends, one Jewish and one Christian, through the equally improbable re-connection with Otto at center stage.

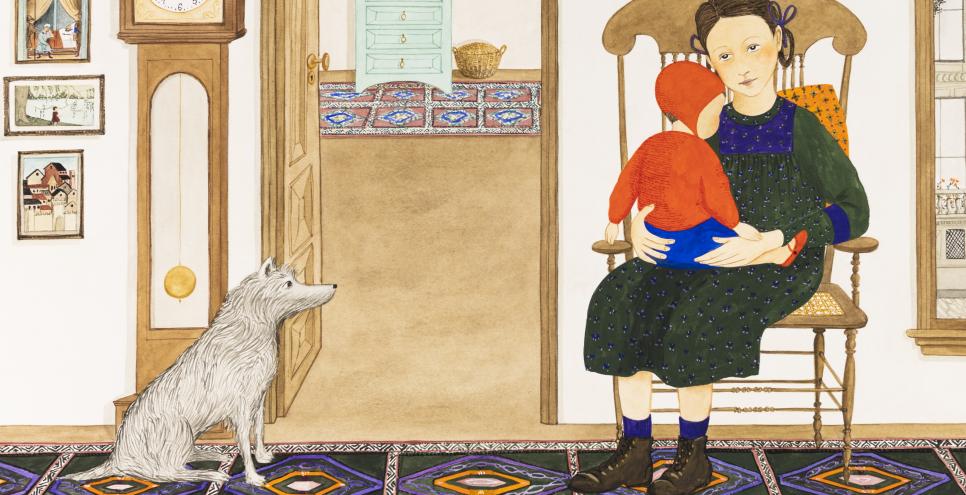

Artistically, Nivola combines a subtle, seemingly untutored clarity with a sophisticated, delicately dappled touch. Intricacy supports an overarching commitment to visual intelligibility where clean, spare lines coexist with luxuriant patterning. She also relishes in insinuating visual references of her varied artistic heroes, ranging from Early Renaissance painter Piero della Francesca, Impressionist Edgar Degas, and modernist Henri “Douanier” Rousseau, in the guise of “paintings-within-paintings.” Nivola observes that she selects postcards from her collection to complement the palette and design of the spread in question. On the back cover of Elisabeth, the triple hang of works adjacent to a tall clock comprise two references to Piero della Francesca and a historical photograph of Ruth taken in Berlin when she was a girl. The uppermost image echoes Piero’s Dream of Constantine, part of the Legend of the True Cross, 1464 (Basilica, San Francesco, Arezzo). The middle image is a painterly depiction of the photograph Ruth provided her daughter, in what must have been a more halcyon time in Berlin.3 The final image in the trio constitutes of a detail from Piero’s Discovery and Proof of the True Cross, ca. 1460, also part of the fresco program for the Basilica of San Francesco, Arezzo.

In the subsequent spread depicting Ruth and Elisabeth riding an exotic turtle around her bedroom, Nivola places on the bed a copy of Heinrich Hoffmann’s Struwwelpeter, an unsettling cautionary tale originally published in 1845 whose popularity endured well into the 20th century. Additionally, she adorns the walls with two works by Rousseau: Liberty Inviting Artists to Take Part in the 22nd Annual Exhibition of the Société des Artistes Independants (1905-06, National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo), unfortunately obliterated by the book’s gutter, and The Pink Lemon (1908, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C). Nivola’s own sophisticated approach to simplicity clearly resonated with this French artist’s work.3

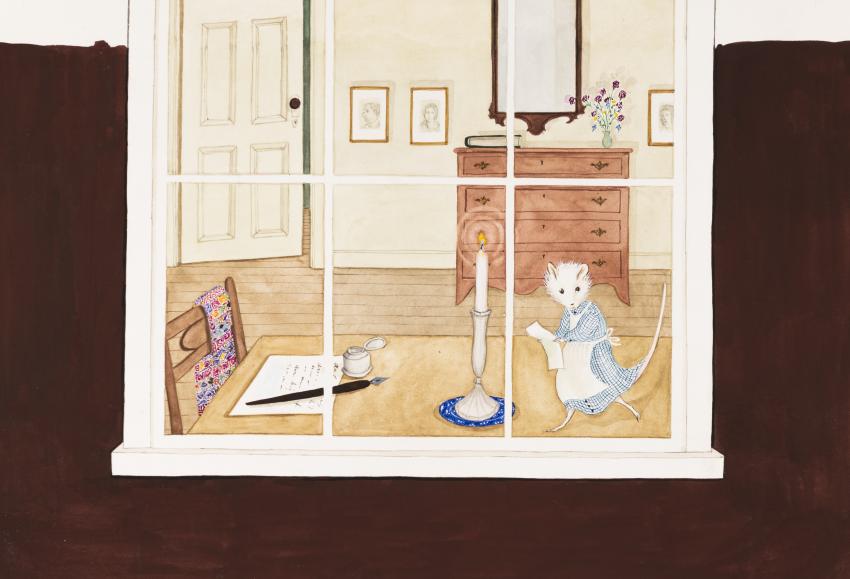

Claire A. Nivola, Illustration for Elisabeth (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). Collection of the artist. © 1997 Claire A. Nivola.

Later in the book, where Nivola depicts herself and her daughter admiring Elisabeth, she opts to include Edgar Degas’s Edmondo and Therese Morbilli (ca. 1865, The National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.) where the green of the daughter’s dress and the orange-red of Elisabeth’s shoes echo elements in the French painting. Like all truly accomplished artists, Nivola possesses an extensive storehouse of art-historical reference and employs it to admirable effect.

Claire A. Nivola, Illustration for Elisabeth (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). Collection of the artist. © 1997 Claire A. Nivola.

Equally compelling is Nivola’s commitment to research to establish authenticity. For instance, in the scene where Ruth returns to her comfortable home, now patrolled by a Nazi soldier, the architecture reflects residential buildings of Berlin in the 1930s, and the soldier wears the accurately depicted uniform of the day. The next spread, showing the railroad station, depicts a train evoking the rolling stock of the era. To this end, Nivola made a highly detailed study of a railroad car. Among the papers in the research folder dedicated to Elisabeth are pertinent photocopies taken from a photographic history documenting the period.4 Still, she took artistic license for some details. In the spread where Ruth pays for the doll, the breast pocket of the proprietor’s jacket is on the wrong side, presumably revealing a desire to add a visual highlight to the otherwise somber coat. Overall, critics praised the book, commenting on the vibrancy of the art as well as the bonds of family.5

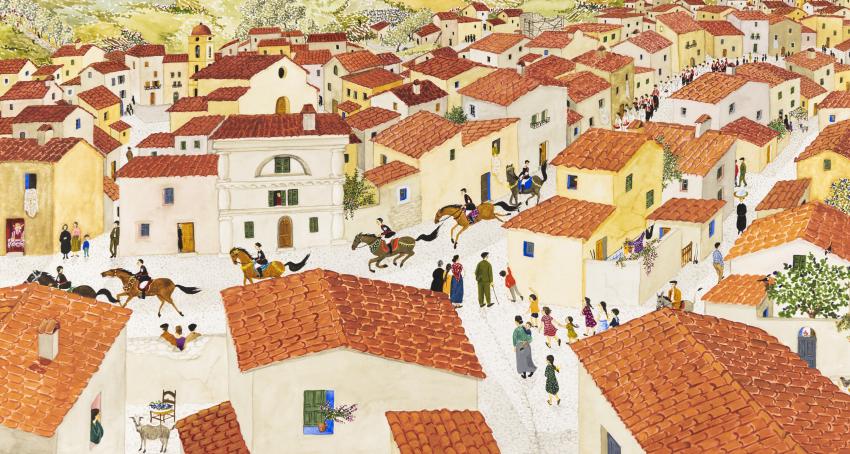

Claire A. Nivola, Illustration for Orani: My Father’s Village (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). Collection of the artist. © 2011 Claire A. Nivola.

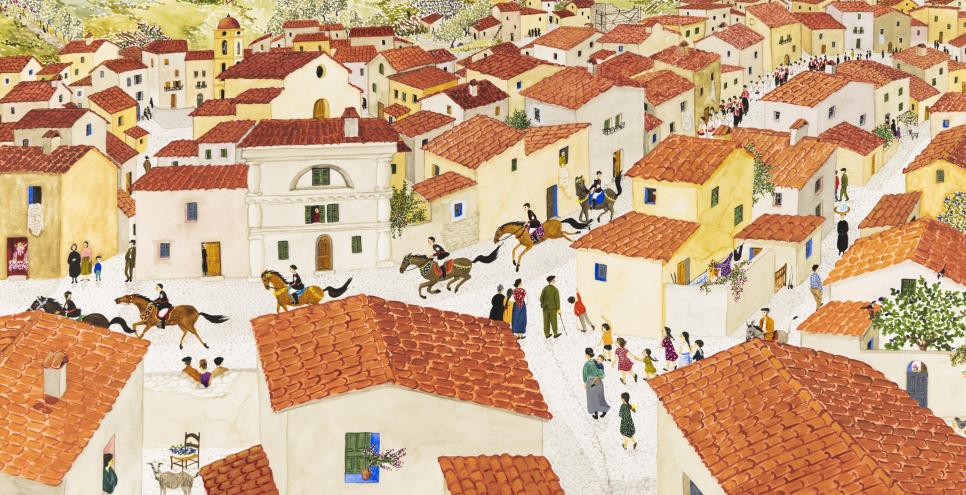

Nivola worked on seven books before she wrote and illustrated Orani: My Father’s Village (2011), also created under the aegis of Frances Foster. This narrative chronicles Nivola’s connection to the birthplace of her father in Orani, a small village situated on the island of Sardinia. As a young girl and beyond, Nivola and her family would return in summers to what she considered an idyllic spot, whose more retardataire way of life effaced the modernity of living in America., From the majestic landscape of the opening spread to the claustrophobic city view at the end, Nivola eloquently addresses issues of rural and urban, old and new.

Claire A. Nivola, Illustration for Orani: My Father’s Village (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). Collection of the artist. © 2011 Claire A. Nivola.

Nivola inserts herself into the narrative, wearing a deep red checkered dress, basking in the simplicity of the life she temporarily shares with her cousins. She revels in the spare cleanliness of the white-washed courtyard, enlivened by chickens, laundry hanging on the line, a carefully tended vegetable garden, and lizards facing off on the stone wall. She assures her inquisitive cousins that life in Orani is superior to that back home in America. The book reflects upon the importance of tradition, such as the spread depicting an annual horse race through the streets on Corpus Christi Day where riders from neighboring villages compete, including bandits. Even in this seemingly utopian world, crime also exists. And so, Nivola offers a world of contrasts. In an interview connected with its publication, Nivola indicated that she had returned to Orani in preparation for the book to understand the landscape and its people and came to the realization that nothing is ideal: tradition has its costs just as modernity does.6

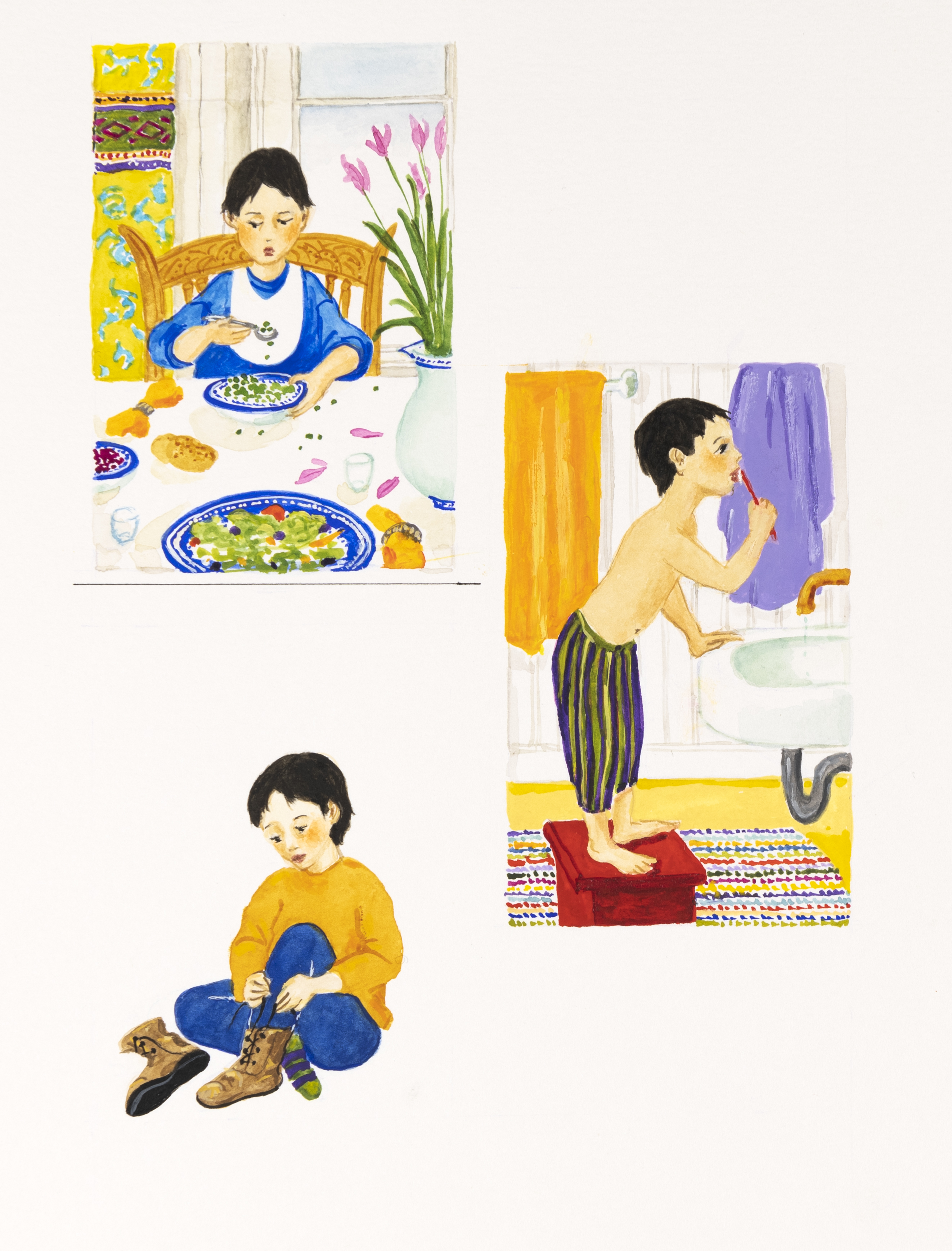

Claire A. Nivola, Illustrations for Orani: My Father’s Village (Farrar, Straus and Giroux). Collection of the artist. © 2011 Claire A. Nivola.

Critics lauded this Proustian exercise, and The Horn Book awarded Orani a starred review.7 The book also garnered international accolades with a prestigious Ragazzi award at the annual Bologna Book Fair that led to its publication by Rizzoli in Italy. At least two reviewers connected Nivola’s art to the folk-art approach of Barbara Cooney, and one of these added Alice and Martin Provensen into the mix.8 These associations are valid, though Nivola’s touch is a bit more painterly or modulated than the other three titans of the field; nevertheless, they share this simpler approach at the service of visual clarity. Librarian and critic Betsy Bird nicely placed the story within the realm of personal family history, connecting it to Robert Lawson’s Caldecott Medal They Were Good and Strong (1940), Donald Hall and Barbara Cooney’s Ox-Cart Man (1979), and William Steig’s When Everybody Wore a Hat (2003). Bird provided a close visual reading of the art, pointing out an anachronism in the final scene. The crush of pedestrians that surround Claire wear far more recent clothing than her 1950s red-checkered dress. Bird considered it a minor point in an otherwise outstanding book.9

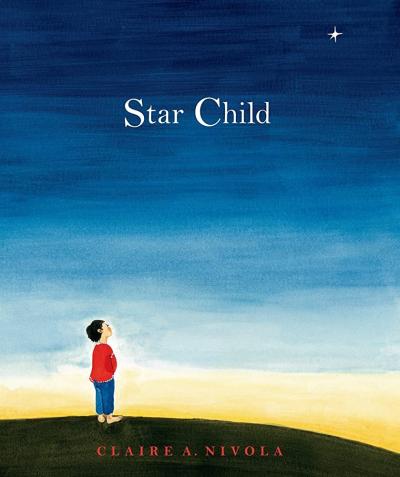

Nivola’s third book grounded in personal history had its genesis in the birth of her son in 1983 and the death of her father five years later. Star Child (2014) also constituted her final collaboration with Frances Foster. In August 1988, Nivola created a little (1 ¾ x 2”) stapled, hand-written book for her son that contained the gist of the story. For the artist, these episodes addressed the wonder of birth and the mystery of death. It wasn’t until 2008, some 20 years later, that Nivola approached Foster to explore the possibility of its publication. Their exchange is telling. First and foremost, Foster invoked a connection to Antoine de Saint-Exupery’s Le Petit Prince (The Little Prince, 1943) by now a revered classic.10 While accepting this allusion with mild reservation, Nivola responded with lines from a poem by Nobel Laureate Czeslaw Milosz (1911-2004), who wrote of the marvels of Earth, while tempering it with a tension between pain and abundance.11 For her, the connective tissue was a shared sense of perspective—a balance of engagement and distance, of positive and negative. Nivola reinforced this contention in an interview when the book was finally published in 2014, indicating that she was not addressing existence or the mystery of life, but rather the experience of life amid its surrounding confusion and wonder.12 Sadly, the publication of the book took on its own moment of poignance, since Foster suffered a devastating stroke during the production and couldn’t bring the book to completion on her own.

The story considers the curiosity of a young star about life on Earth, whose elders say it can make the journey if it is willing to assume the life cycle of a human. Thus, the tale unfolds from infancy to death, culminating in the star’s return to the galaxy. Nivola pointedly provides generic settings, from jungle to New England village, to give a sense of what she describes as “anyone, anything.”13 The scenes, with some exceptions, reflect the normalcy of everyday life, captured in the artist’s signature delicate, painterly touch, alternating between broad wash and almost pointillist stippling. Although the critic for the Kirkus Reviews questioned its appropriateness for a younger audience “in the throes of becoming,” the book garnered many favorable reviews.14

However, sales languished, and the publisher let the book go out of print. Consequently, the rights reverted to Nivola. This rumination on the cycle of life caught the attention of writer/director Mike Mills who used it in his 2021 film C’mon C’mon, released by the independent production and distribution company A24. Mills had read this book repeatedly to his young son and transferred this emotional experience into a touching scene in the movie. Taken with the narrative and the opportunity for a commercial tie-in, A24, with Nivola’s assent and guidance, re-issued the book in an elegant edition, replete with slipcover and gatefolds. The A24 creative team, in collaboration with the artist, created an entirely new format, digitally enlarging the illustrations for slightly larger, more vertical pages. Where once several vignettes populated a single page in the original edition, the new version gives every image its own space, providing an enhanced sense of focus to each episode. Ironically, in the wake of the movie’s release, the original edition of Star Child became highly desired and its price on the used book market soared. Happily, the new edition now makes it eminently affordable.

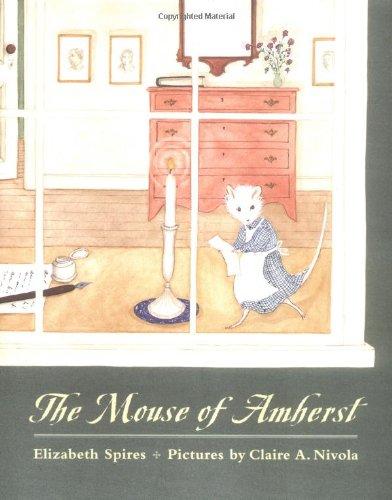

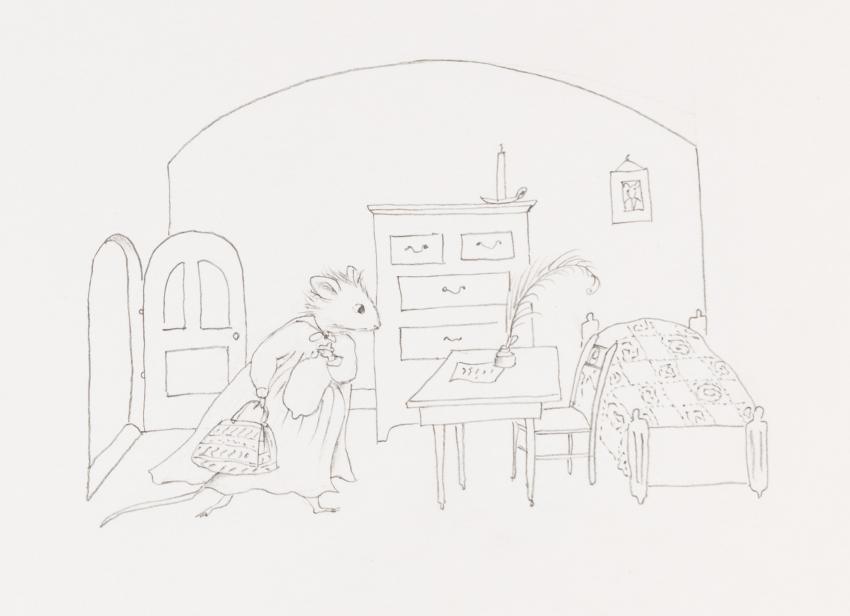

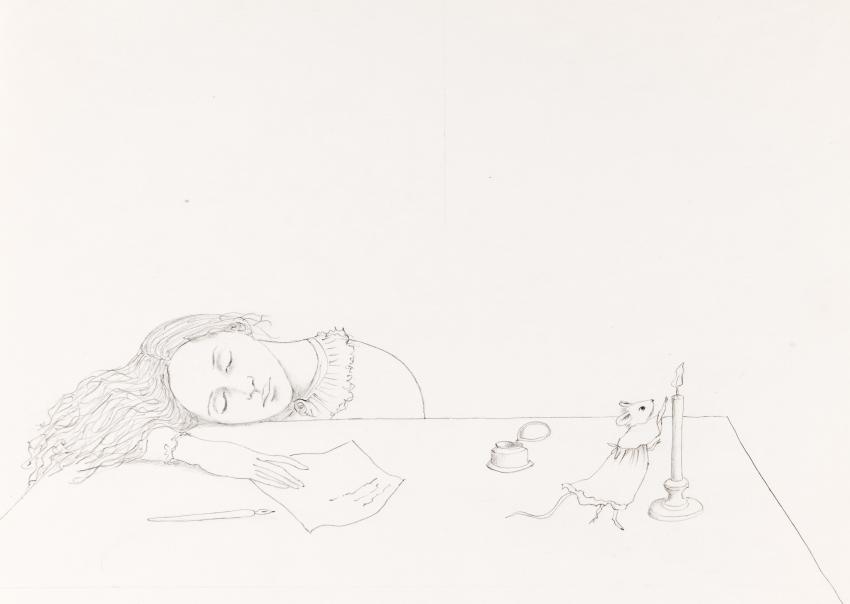

The Mouse of Amherst (1999), a fanciful account of the friendship between a mouse named Emmaline and the poet Emily Dickinson, takes place in Dickinson’s home in Amherst, Massachusetts. Elizabeth Spires, a Professor of English Literature and accomplished poet, wrote the text. In a letter written while the book was in progress, Spires praised Nivola for her visual interpretation, noting, “Emmaline is just right, a young, warm, vulnerable looking mouse… I also thought you did a wonderful job with the Dickinson family members, and really captured Emily’s wild, beautiful spirit in the sketch of Emily asleep next to her candle.”15 Evidently, Nivola achieved this success through the plethora of preliminary studies which contributed to capturing just the right effects.

In this exercise of anthropomorphism, Nivola joins such efforts as Robert Lawson’s Ben and Me (1923) and Garth Williams’s illustrations for E. B. White’s Stuart Little (1945), to bring this humble creature into the human realm. The slightly tremulous draftsmanship echoes the deft approach of William Steig who often favored mice as protagonists. Coincidentally, Steig was a family favorite when Claire and her husband read to their children. Nivola confines herself to the graphic simplicity of pencil illustrations and requested that their contrast be heightened when printed so they would have both the softness of pencil and the blackness of ink. The diminutive heroine and intimate narrative also required a more modestly-sized book. Measuring a mere 7 ¼ x 5 ¾”, The Mouse of Amherst evokes the even smaller volumes by Beatrix Potter, who determined that her books should be easily grasped by young children. While Potter’s tales were intended for a slightly younger audience than Nivola’s, the intent was the same.

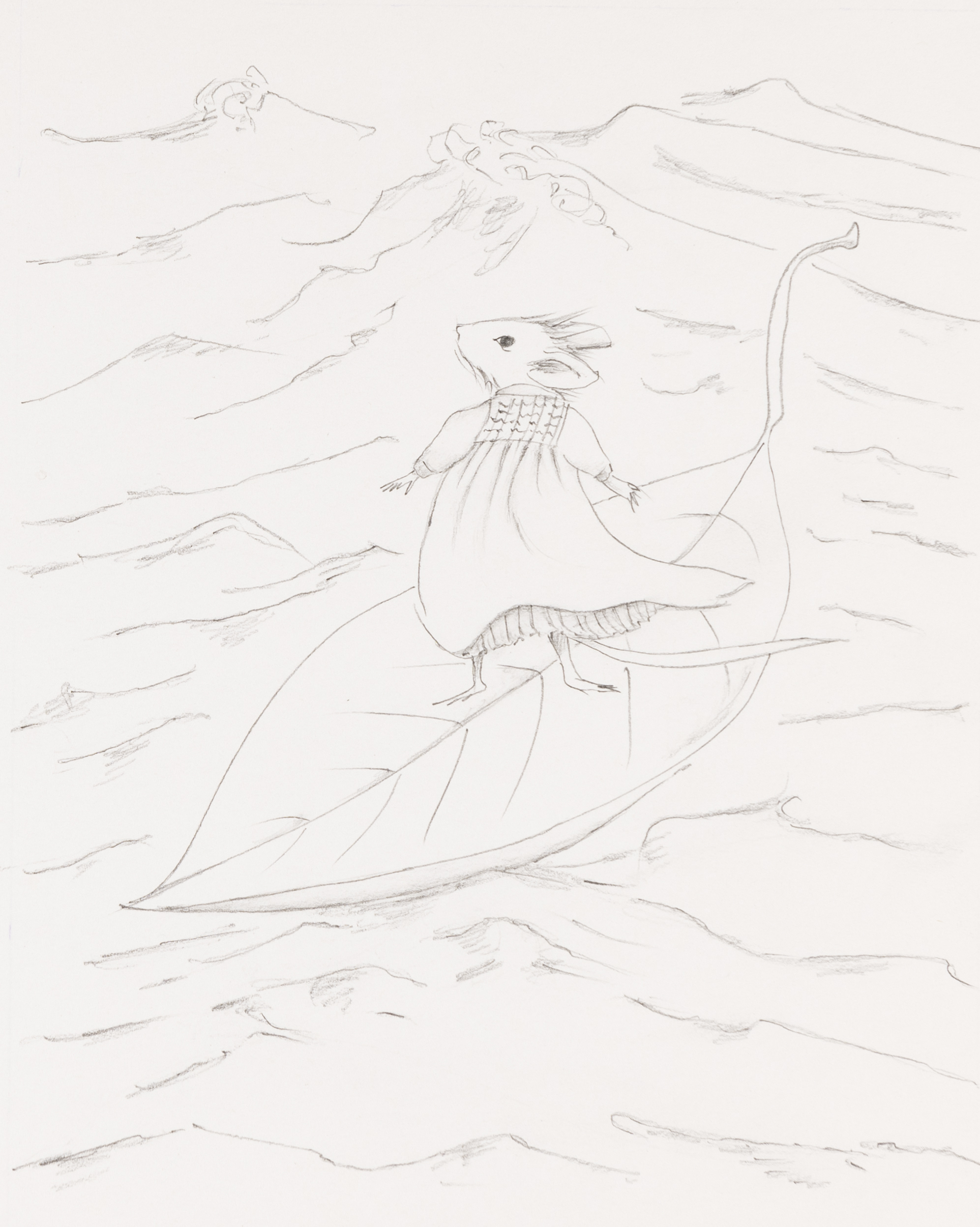

In a dramatic scene at the end of the book, Emmaline, inspired by Dickinson’s maritime poem, imagines how she might escape the threats of Emily’s sister Lavinia, sailing over the wide sea on a leaf. In this instance, the episode recalls the travails of Abelard Hassam deChirico Flint, otherwise known as Abel in Abel’s Island (1973) as well as that of Stuart Little sailing on the Conservatory Water, the sailboat pond in Central Park. It reinforces the notion that animals, like humans, are vulnerable to the forces of nature. Emmaline will go on to raise a family and pass on her love of poetry to her own children.

Nivola’s next project was illustrations for Amy Hest’s The Friday Nights of Nana (2001). This story embodies a fictionalized account of an authentic Jewish observance, the Friday Shabbat. The story is a charming account of the preparations for the evening meal undertaken by grandmother and granddaughter. The final dinner scene, a vertical composition viewed through a sectioned window from outside, recalls Norman Rockwell’s iconic Thanksgiving depiction Freedom from Want (1941, The Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Massachusetts). Rockwell’s oil painting was inspired by President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s State of the Union Address themed “The Four Freedoms.” Nivola’s sequence from the previous, expansive horizontal spread of the dinner to this more compact iteration suggests a heartwarming continuity around the table.

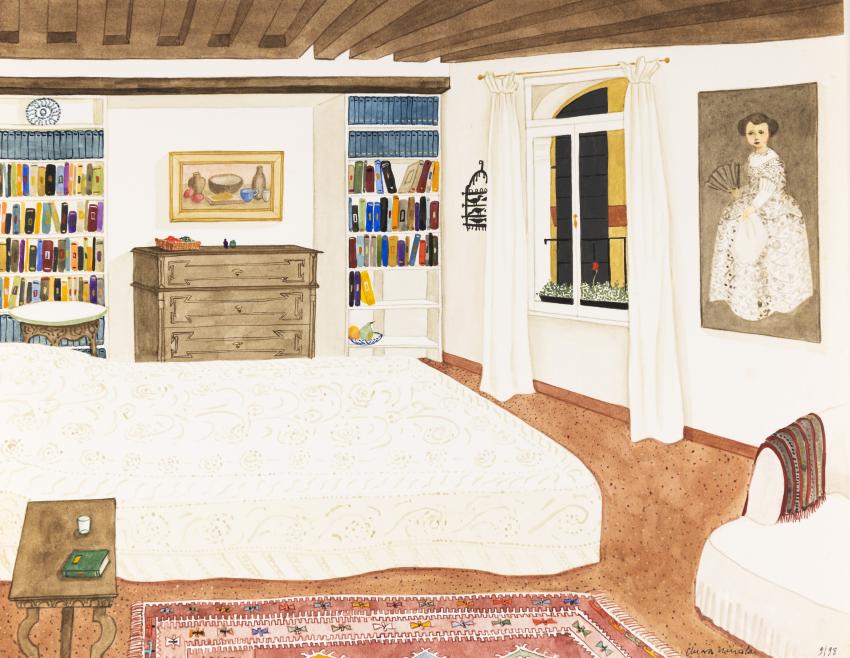

Artistically, Nivola continues her commitment to the interplay of simple shapes and complex pattern. As well as revealing her love of flower arrangements, she continues to include visual references to art she admires. Henri Matisse’s Interior with a Violin Case (1918-19, Museum of Modern Art, New York) makes two appearances—once in the guise of a calendar and subsequently as a framed stand-alone work in the vertical image above. In the scene where the grandmother sets the table, a large canvas of a young girl dominates the space between the windows. Nivola’s inspiration was an 18th-century portrait that adorned the guest room of friends she visited in Venice. She made a painting of this room from memory and eventually adapted the portrait for Nana’s dining room. The Friday Nights of Nana remains one of Nivola’s favorite projects, undoubtedly conditioned by the warm feeling of the narrative and the opportunity to provide such a rich domestic array.

Claire A. Nivola, Study for house interior, n.d. Collection of the artist. © Claire A. Nivola.

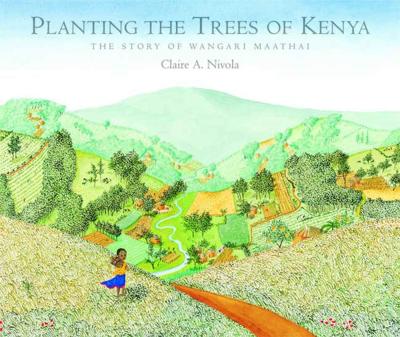

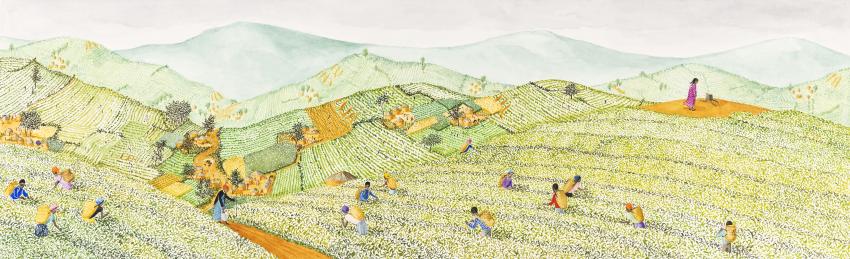

The world of Nivola’s art extends beyond family history, having previously illustrated two books by other authors based on episodes in 19th-century American history.16 Her first solo foray in this genre, Planting the Trees of Kenya: The Story of Wangari Maathai (2008), stems from her own profound commitment to environmental issues, especially climate change. In an interview titled “Meet the Author,” Nivola recounts the genesis of the book emanated from a radio program that aired in 2005 subsequent to Maathai (1940-2011) winning The Nobel Peace Prize in 2004.17 Once the project commenced, both author and editor—once again Frances Foster—were determined to make the story as accurate as possible. In a letter to Nivola dated June 14, 2006, Foster insists she not only capture the “soul of Wangari’s work,” but also stipulates that she (Foster) needs, “ … your constant reassurance that you are following sound reference for the landscape, how the people dress, types of dwellings and farm structures, school uniforms, etc.”18 This concerted effort included submitting sketches and text to Maathai for approval, but word came back that she was too busy to undertake this, indicating she had faith in the creator’s intentions. True to her own environmental agenda, Nivola inquired whether the book could be printed on recycled paper to which Foster responded that while the economics still dictated against this approach, the book would be an excellent candidate.19 To Nivola’s great delight, the book is printed on recycled paper.

The narrative opens with Maathai standing in a lush field, looking at the reader, while set against a magnificent panorama of the verdant landscape of her girlhood home of central Kenya. She travels to America for her college education, earning a degree in Biology. Upon her return to Kenya, Maathai witnesses the degradation of the landscape through deforestation (which also created dire economic consequences). Through a concerted grassroots effort, she achieves extraordinary success in effecting a return to Kenya’s former natural glory. A series of double-page spreads chronicling this decline precede a group of more tightly focused episodes delineating the restoration process. While Nivola is committed to a true picture, she doesn’t allow her art to become bogged down in minute detail. Her pictures retain a lively sense of freshness, an energy anchored by plausibility. Reviews were laudatory, and the esteemed historian of children’s books Barbara Bader concluded her review, “The whole is as much a pleasure as an inspiration.”20 Significantly, the book garnered The Jane Addams Award, which annually recognizes children’s picture books that inspire children to think about peace, social justice, global community, and equity for all people.

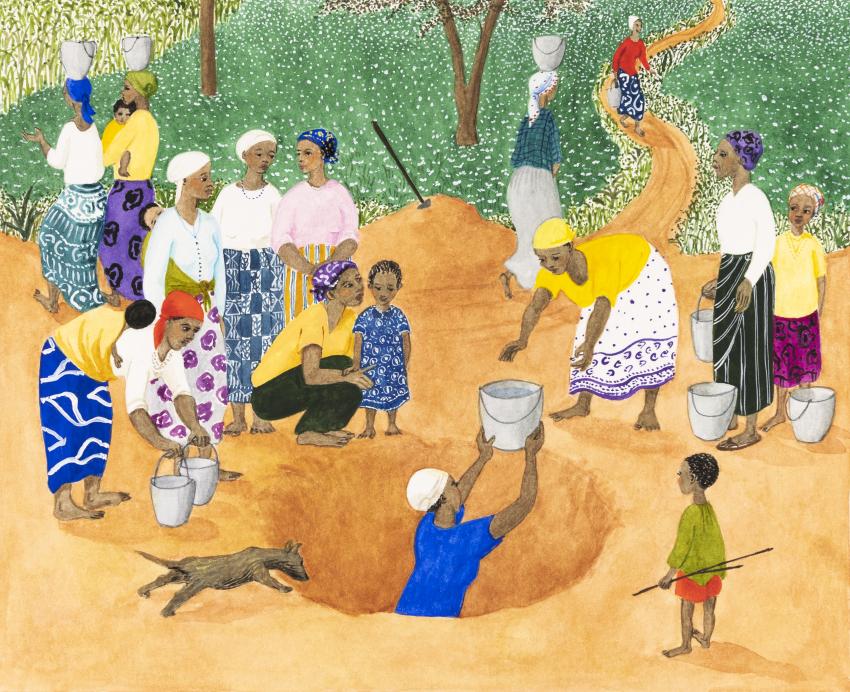

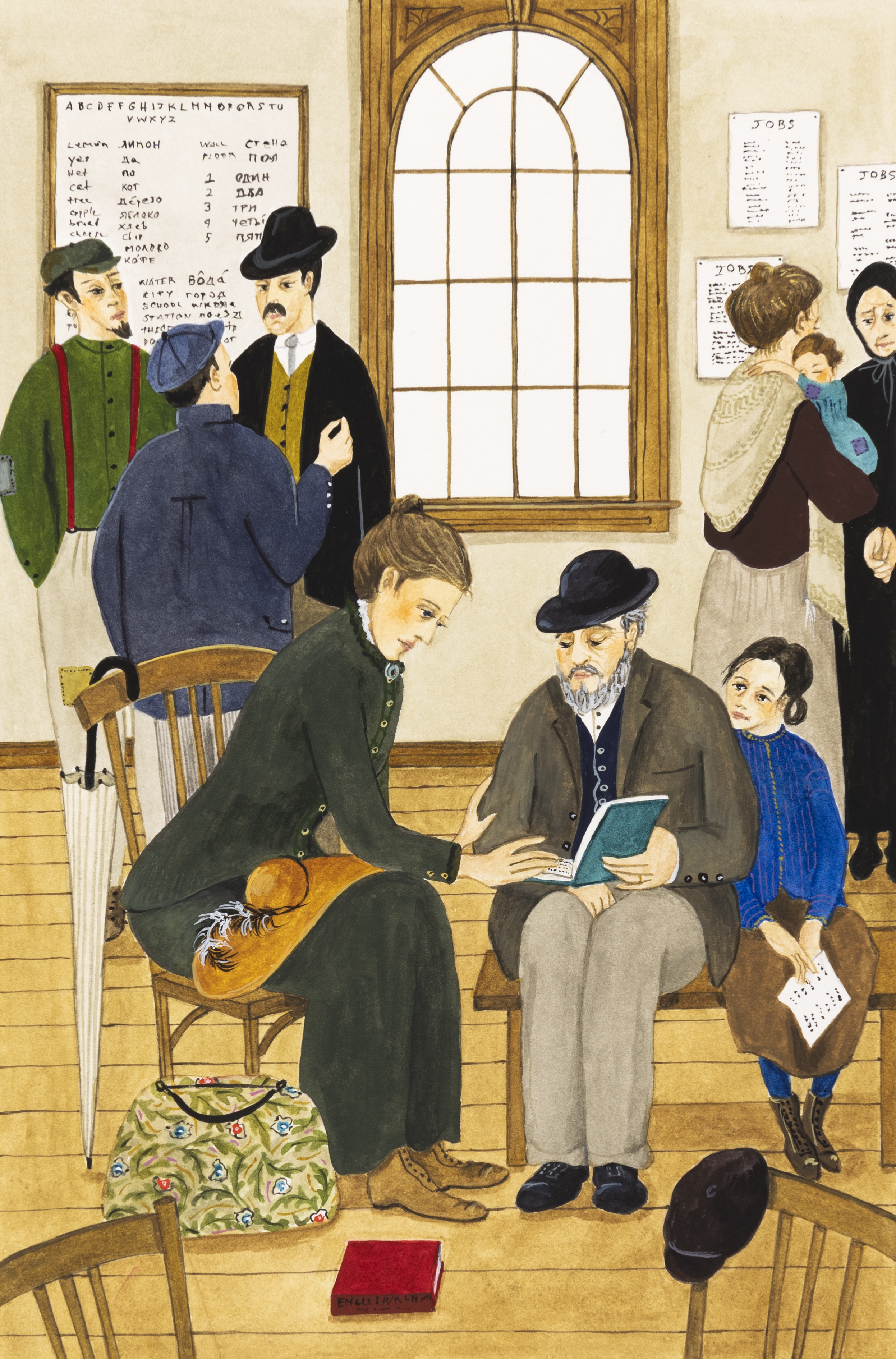

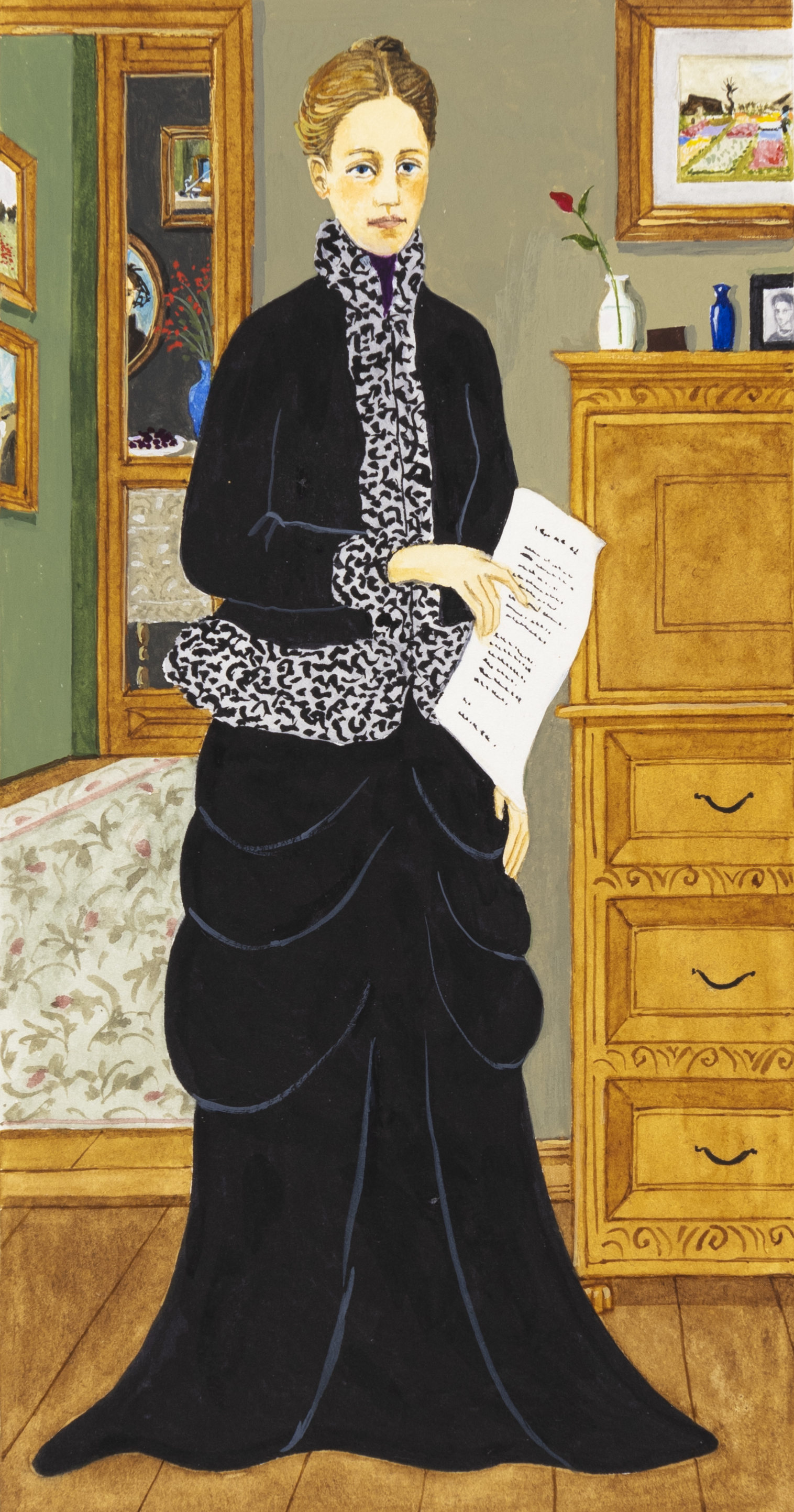

Having illustrated two books of historical nature for the prominent publishing house Houghton Mifflin Company, Nivola received another overture to illustrate the story of Emma Lazarus’s legendary poem, “The New Colossus,” that welcomes immigrants on the Statue of Liberty. Ann Rider, Houghton’s executive editor for children’s books, wrote Nivola of her appropriateness for the project because of her “attention to detail, but also because of your gentle faces, your quiet power.”21 Written in the spring of 2008, early in the nomination process for the Presidential election, Rider underscores the importance of framing this story in the context of a picture book, and its timeliness in the current climate about immigration.

Claire A. Nivola, Illustration for Emma’s Poem: The Voice of the Statue of Liberty by Linda Glaser (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). Collection of the artist. © 2010 Claire A. Nivola.

Once again, Nivola conducted extensive and thorough research as she scoured pictorial histories and illustrated magazines of the period. Several photographs, especially of ships entering New York harbor with the Statue of Liberty in the distance and images of immigrant children at play and at school, served as direct models for her visualizations. As well as referencing photographs of Lazarus for veracity, Nivola turned to Harper’s Weekly for guidance of the upper middle class’s taste in fashion, her protagonist’s social milieu.

Visually, the narrative comprises a poignant alternation between opulence and indigence with Lazarus bridging the divide. The scenes of her social situation reflect the taste for Victorian excess couched in an ambience of entitlement, while her forays into the immigrant world portray poverty, austerity, and anxiety. The illustrations are signature Nivola, a reductive imagery that meshes clarity and delicacy. The book received the Sydney Taylor Honor Award, given to outstanding books for children and teens that authentically portray the Jewish experience.

Anyone perusing recent issues of magazines such as The New Yorker or Vanity Fair would have encountered a Rolex watch ad featuring such female luminaries as Olympic skier Lindsey Vonn, concert pianist Yuja Wang, actress Grace Kelly, and … oceanographer Sylvia Earle.22 As with Wangari Maathai, Nivola happened upon Earle through a radio program, and, similarly, gravitated to Earle’s personality and deep concern for the environment.23 Having grown up near the water on eastern Long Island herself, Nivola shared a familiarity with marine life.

From her youth, Earle marveled at the wonders of the natural world in all its manifestations. She spent her early childhood on a farm in New Jersey, exploring the woods, creek, and pond on the property, making detailed notes and drawings of the flora and fauna she encountered. She captured and housed specimens in collection jars, and Nivola elegantly illustrates such a moment where young Earle, amid a richly detailed natural setting, studies and sketches a dragonfly.

When she was twelve, Earle’s family moved to the west coast of Florida and the Gulf of Mexico became her laboratory. Her youthful passion for nature became her profession, and Earle emerged as the first professional female oceanographer, overcoming the obstacles placed in a woman’s path at the time. She probed deeper and deeper into the ocean’s depths, providing extraordinarily pioneering insights into aquatic life.

Nivola, true to her standards for accuracy, undertook extensive research, evidenced by the extensive bibliography at the back of the book. She created numerous highly-detailed preliminary drawings of her aquatic subjects, consulting with both Earle and Dr. James McCarthy, Alexander Agassiz Professor of Biological Oceanography at Harvard University, about the accuracy of her depictions. From the size of a humpback whale’s eye to the length of sea grasses and configuration of bamboo coral, no detail was too insignificant. Earle was supportive of the artist’s approach, but also encouraged her not to deny herself artistic license.24 Consequently, the imagery comprises an intelligent blend of macro- and micro-organisms. While providing glorious depictions of an unsullied ocean, Nivola, in philosophical concert with her subject, concludes the narrative with a clarion call for greater commitment to conservation issues.

More recently, Nivola takes on the biography of Nek Chang, a visionary artist from India. Coincidence also provides an intriguing symmetry since this project, like Betty Jean Lifton’s Tell Me a Real Adoption Story (1994), fell into her lap unsolicited, triggered by her interest in India.25 The story of Nek Chand resonated, since Nivola, under the tutelage of her father, had carved small figures out of setting concrete as a child. She also empathized with the trauma of Chand’s dislocation and sense of loss.

Chand spent his youth in the Punjab region of colonial India that was partitioned into Pakistan after India gained independence in 1947. Hindus were forced to relocate from this predominantly new Muslim entity and, in 1951, Chand and his family settled in Chandigarh. Designed by the eminent French modernist architect Le Corbusier, Chandigarh constituted India’s first planned city.

As a child, Chand reveled in building imaginary worlds out of silt, clay, sticks and rocks by the village stream. The severe rectilinear grid of Chandigarh and its buildings distressed Chand, and his occupation as a road inspector afforded him the opportunity to explore the countryside. Chand, in defiance of local ordinances, commenced his ambitious project in secret in a remote area on the outskirts of the city. Threatened with destruction upon discovery by the authorities, Chand’s magical kingdom was saved through the intervention of the local citizenry. Despite continued opposition from the government, this remarkable endeavor survives as the largest visionary environment in the world and connects in spirit to Howard Finster’s equally mystical Paradise Garden in Summerville, Georgia.

Predictably, Nivola’s research folder for the book is thick with documentary photographs and drawings based on them. In one case, Nivola uses a photo of a woman riding a bicycle with a 55-gallon drum balanced on her head for the image of Chand bringing raw materials to his work site.26 Additionally, she turned to the Fondation Le Corbusier for guidance on the history and layout of Chandigarh, receiving much helpful information;27 her scrutiny of India’s vernacular architecture and indigenous flora and fauna was no less thorough.

The art is quintessential Nivola, with its by now familiar blend of dappled detail and broad lush brushstrokes. Her painterly treatment of Le Corbusier’s central building effectively softens its severe and imposingly sterile presence. Compositionally, the book presents an engaging alternation of landscape and stage-like settings with more flowing arrangements articulated by curves and counter curves. And to the credit of the book’s designer, the text never distracts from the visual experience. The Secret Kingdom possesses a compelling organic flow, highlighted by the culminating gatefold that opens into a panorama of the actual garden, thus bringing imagination and fact into alignment.

Claire Nivola merits more recognition in the world of children’s books. She sets the highest standards for herself and brings consummate skill and intelligence to whatever project she undertakes. She handles the challenging medium of watercolor with deftness and supreme confidence. With steadfast messages and priorities, she advocates for issues of social justice and preserving the environment. As a champion of accomplished individuals, she introduces the young reader to the power of potential and determination.

1 Claire Nivola to Frances Foster, dated November 12, 1995; photocopy retained by the author.

2 Ruth Nivola to Claire Nivola, undated hand-written letter; in the possession of the artist.

3 Photocopy of undated original photograph in the possession of the artist.

4 See Thomas Friedrich, Berlin Between The Wars [New York: the Vendome Press, 1991], pp. 70 et passim.

5 Anon., Elisabeth, Kirkus Reviews, https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/claire-a-nivola/elisabeth/ retrieved 11/04/2022 and Susan Bloom, Elisabeth, The Horn Book Magazine, May/June, 1997, pp. 310-311.

6 Jennifer M. Brabander, “Five Questions for Claire Nivola,” in “Notes from the Horn Book,” https://www.hbook.com/story/notes, October 6, 2011, retrieved 11/04/2022.

7 Joanna Rudge Long, Orani: My Father’s Village, The Horn Book Magazine, September/October 2011, pp. 112-13.

8 Robin Smith, “Calling Caldecott,” in “Articles and Opinion,” https://www.hbook.com/story/notes, October 4, 2011/ retrieved 11/04/2022 and Betsy Bird, “Claire Nivola – Orani,” Fuse 8, School Library Journal, July 16, 2011, https://afuse8production.slj.com/2011/07/16/review-of-the-day-orani-my-fathers-village-by-claire-a-nivola/ retrieved 11/04/2022.

9 Bird, Ibid.

10 Email from Frances Foster to Claire Nivola, April 18, 2008, copy retained by the artist. Another book that addresses the celestial curiosity about earth is Tomi Ungerer’s Moon Man, originally published in 1966. Attracted by the views of happiness and good times, the protagonist visits Earth, only to find it was not all he thought it would be.

11 Email response from Claire Nivola to Frances Foster, April 18, 2008, copy retained by the artist. The line in question reads, “In the hall of pain, what abundance on the table.” See, Czeslaw Milosz, New and Collected Poems: 1931-2001 [New York: Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins, 2001], p. 377.

12 Email from Claire Nivola to Jules (seventhings@gmail.com) April 16, 2014, copy retained by the artist.

13 Ibid.

14 Anon., Star Child, Kirkus Reviews, May 6, 2014 https://www.kirkusreviews.com/book-reviews/claire-a-nivola/star-child/ retrieved 11/04/2022.

15 Elizabeth Spires to Claire Nivola, February 27, 1997, in the possession of the artist.

16 See Susan Campbell Bartoletti The Flag Maker [Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004] about the “Star Spangled Banner,” and Robin Friedman, The Silent Witness [Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005] about the first battle of Bull run in the Civil War.

17 Toni Buzzeo, “Meet the Author,” https://www.librarysparks.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/lsp_mar2010_mta_claire_a_nivola.pdf/ retrieved 11/04/2022.

18 Frances Foster to Claire Nivola, June 14, 2006, in the possession of the artist.

19 Email exchange between Claire Nivola and Frances Foster, October 28, 2006, copies retained by the artist.

20 Barbara Bader, Planting the Trees of Kenya: The Story of Wangari Maathai, The Horn Book Magazine, May/June 2008, pp.339-340.

21 Ann Rider to Claire Nivola, March 13, 2008, in the possession of the artist.

22 See The New Yorker, March 28, 2022, pp. 4-5.

23 “Sylvia Earle’s Life Aquatic,” interview with Tom Ashbrook, On Point, WBUR and NPR, February 9, 2009.

24 Sylvia Earle to Claire Nivola, email dated 11 October 2010, copy retained by the artist.

25 Claire Nivola, https://www.teachingbooks.net/tb.cgi?aid=8755/ retrieved 11/04/2022.

26 Rachel Smith to Claire Nivola, email dated October 8, 2015, copy retained by the artist.

27 Antoine Picon to Claire Nivola, email dated March 22, 2015, copy retained by the artist. As well as a chronology for the realization of Chandigarh, M. Picon attached a plan of the city. Antoine Picon is a member of the board of Directors of the Fondation and also teaches part-time at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where Nivola tracked him down.