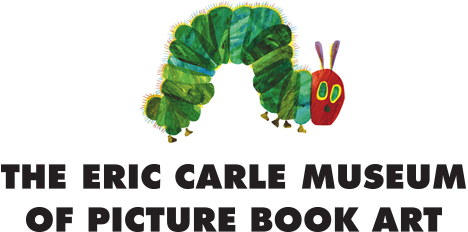

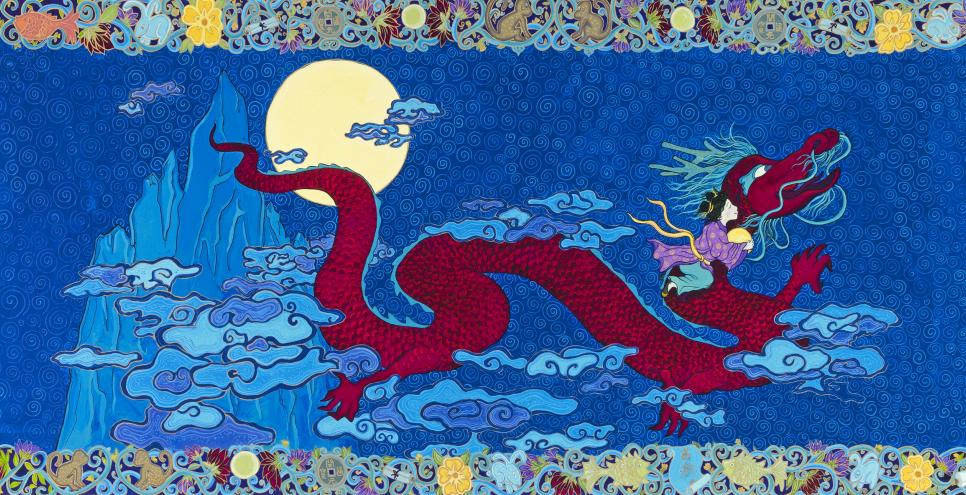

Grace Lin, Illustration for When the Sea Turned to Silver (Little, Brown Books). Collection of the artist. © 2017 Grace Lin.

The Creative Threads of Grace Lin

When I meet the author and artist Grace Lin for lunch in the fall of 2024, our conversation touches on the topic of our upbringings as Asian American in different parts of the country. I’m a Southern Asian from Houston, Texas, the eldest child of immigrants from Hong Kong. Lin is an East Coast Asian, born to Taiwanese immigrants in upstate New York. We quickly agree that we’re envious of West Coast Asians, particularly Californians who grew up surrounded by many other Asian Americans, which was not our experience.

Although I was often the only Asian American in my elementary school classes, at least Houston had a burgeoning (and now sprawling) Asiatown, which my family would visit on the weekends. Lin, however, grew up in a town where there were few families of color, and she rarely saw other Asians. A voracious reader, she also didn’t encounter any characters who looked like her in books. Though she was clearly different, no one ever spoke about it, which made her feel that her race was something to be ashamed about. Lin grew up not wanting to be Asian. This childhood disconnect from her heritage—and her eventual reclamation of it—would have an important impact on her work as she came into her own as an artist.

Lin attended the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), where she diligently studied the great European artists like Michelangelo and René Magritte. During a semester abroad in Rome, she realized that while she could talk at length about Western art, she didn’t know any Asian art. She didn’t even know her parents’ immigration stories. She began to seek out Asian art on her own.

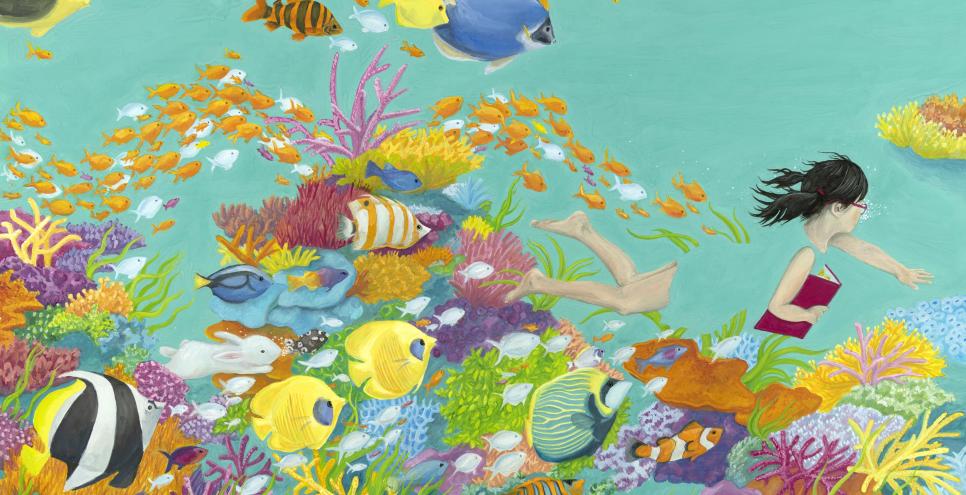

“What I really liked was Chinese folk art, which is very bright colors, a lot of pattern, very flat, not paying too much attention to perspective,” Lin told Poets & Writers in 2010. “At the same time, we were studying Matisse who was doing a similar thing, but in a different way. I tried to mix those two together to make my own style, kind of Asian American. I wanted my style to reflect the mix that I felt that I was.”

Lin’s illustrations often employ a Western-style composition with a central figure or scene unfolding while bright colors, playful patterns, and a flat perspective reflect the influence of Chinese folk art. Not content with panes of solid color, Lin enjoys adding patterns to everything from clothing to backgrounds, and even the sky. She often paints swirls in the sky as a shorthand for clouds—and an homage to Vincent van Gogh’s celebrated painting, Starry Night.

In 1999, Lin got her break with her first picture book, The Ugly Vegetables. She had sent sample illustrations to an editor, who then asked if she had a story to go along with them. Lin did not—the assumption when she was at RISD was that artists would be illustrating someone else’s story—but she told the editor that she did, then got to work writing one. (Today, Lin almost always writes the story first before illustrating.)

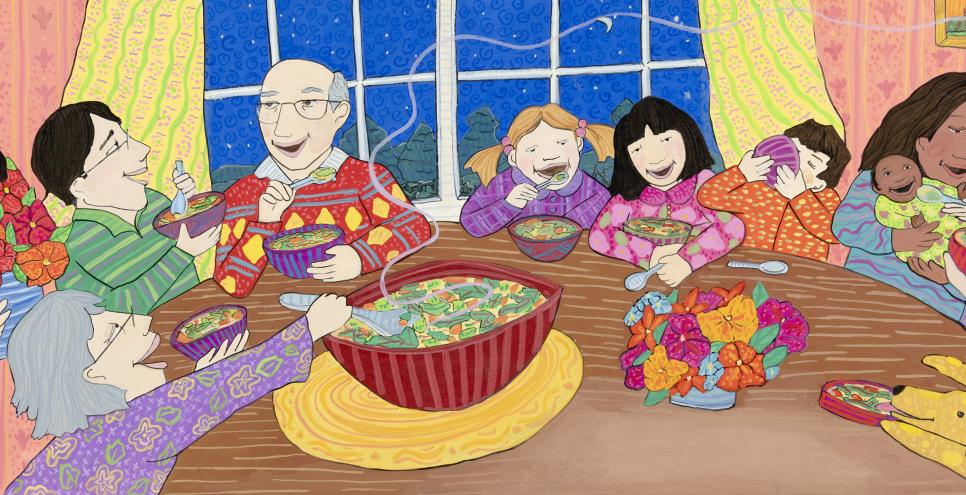

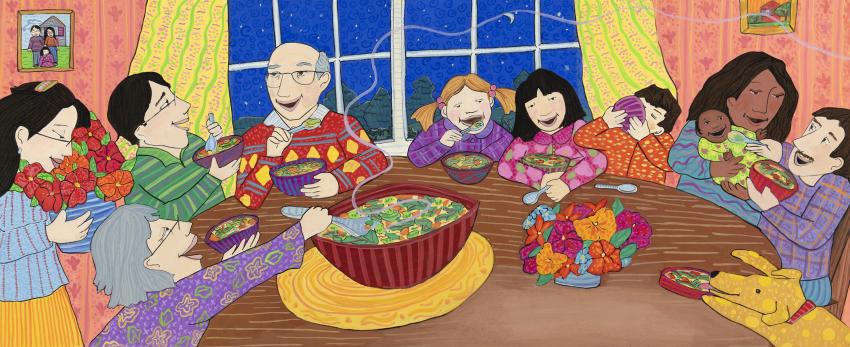

Grace Lin, Illustration for The Ugly Vegetables (Charlesbridge). Collection of the artist. © 1999 Grace Lin.

In The Ugly Vegetables, a girl learns to appreciate her mother’s backyard garden after initially feeling embarrassed that her mother grew Chinese vegetables and not flowers like the neighbors. When her mother cooks a soup from the vegetables, its enticing aroma brings the neighbors together for a joyful dinner. It is a tale of acceptance and of the richness that comes from different foods and cultures.

Lin’s own childhood memories inspired The Ugly Vegetables, and many of her early picture books are autobiographical. Dim Sum for Everyone! (2001), Kite Flying (2002), and Fortune Cookie Fortunes (2004) are all narrated by a girl who is the middle of three sisters, just like Lin. By writing herself and her family into her books, Lin fulfilled her own childhood wish of seeing books with Asian American characters.

Grace Lin, Illustration for Kite Flying (Dragonfly Books). Collection of Brigitte Sierpien. © 2002 Grace Lin.

But with little diversity in children’s book publishing in those early days of her career, Lin was warned that she would be pigeonholed as a “multicultural” author if she only wrote about Asian Americans, and that her books wouldn’t sell well. So, for a while Lin created picture books with animal protagonists, like Olivina the chicken and Marklee the monkey. But at book signings, she noticed that people more often brought her books featuring Asian characters. Asian American parents would tell her that they had been looking for a book like hers. These were the books that resonated and mattered to other people, she realized, and the ones that were closer to her heart.

Yet, Lin’s work has not been without criticism from her own community. When The Ugly Vegetables was published, an Asian American woman wrote to Lin expressing dismay that the main character had a bowl haircut. The woman accused Lin of reinforcing stereotypes of Asians.

“That was a wakeup call. There were so few Asian American books that people were looking at [my work] to represent all of Asian America,” says Lin, who is an advocate for diversity in children’s literature today. “I felt a lot of pressure, and a lot of imposter syndrome, and a lot of ‘I’m not Asian enough to do this.’” For many years, Lin stuck to autobiographical stories as a defense against this criticism, because she could argue that her books were authentic to her own experiences.

Grace Lin, Illustration for Chinese Menu: The History, Myths, and Legends Behind Your Favorite Foods (Little, Brown Books). Collection of the artist. © 2023 Grace Lin.

The author Viet Thanh Nguyen calls this state of underrepresentation “narrative scarcity,” the notion that when there are so few opportunities to tell our own stories and see ourselves represented, every portrayal carries the burden of expectation. “If you come from a so-called minority, let’s say me as an Asian American, you live in a condition of narrative scarcity. Almost none of the stories are about you,” Nguyen said in an interview for the Los Angeles Times Festival of Books. “So when a story about you or someone like you comes along, you put enormous weight on that story.”

Narrative scarcity is the reality for people of color and other minorities. Its opposite is what Nguyen calls “narrative plentitude.” We will know we have reached narrative plentitude, Nguyen says, when we have the luxury of making mediocre art—when so many stories exist the mediocrity of one will not feel like such a disappointment. In a state of narrative plentitude, it won’t feel like the future of Asian American films depends on how well Crazy Rich Asians performs at the box office. And a bowl cut will be just one of many possible hairstyles that a character could sport.

While we are not there yet, Lin has contributed to plentitude by publishing at a prolific pace. Over her 26-year career, she has written and illustrated more than 30 books, from board books to early readers to middle grade novels. (And that number doesn’t include books by other authors that she’s illustrated.)

Her middle grade novels are inspired by Chinese myths and pushed her to grow as an artist beyond the autobiographical. She began writing Where the Mountain Meets the Moon (2009) when her first husband, Robert, had cancer. She would entertain him with what she had written while he was undergoing chemotherapy. Initially, she wasn’t sure she wanted to publish it. She had taken a lot of liberties with myths, mixing and reimagining them. But then Robert died, which gave her a “sense of reckless courage.” What did it matter if someone criticized her? She had nothing to lose. “I started to take ownership of my art,” she says.

Lin’s work also took a leap after she had her daughter. As a new mom, she struggled at first with finding the time to make art. She tried to separate her personal life from her work life, writing at 3 a.m. while her family slept. But only when she embraced the messiness of being both a mom and artist at once did her creativity flourish.

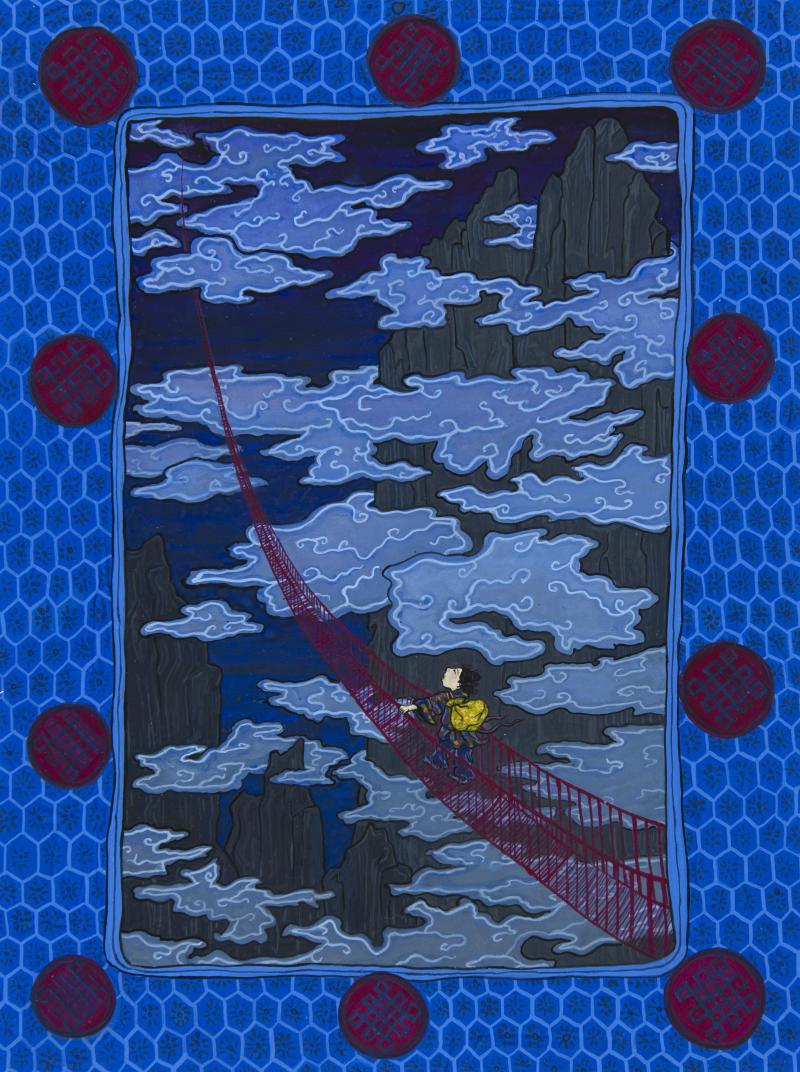

Grace Lin, Illustration for A Big Mooncake for Little Star (Little, Brown Books). Collection of the artist. © 2018 Grace Lin.

A Big Mooncake for Little Star (2018) marks this turn in Lin’s work. It tells the story of a girl sneakily nibbling on an enormous mooncake night after night, representing the phases of the moon. The picture book was inspired by Lin’s own daughter, who once ate all the mooncakes that Lin had purchased for the family’s Mid-Autumn Festival celebration. Visually sparser, it makes use of a retrained color palette and negative space. Lin considers it her best work. “I made this book because I was a mom, not in spite of being a mom,” she says.

The endpapers show Little Star and her mother in the kitchen, mixing ingredients for mooncakes, an homage to Robert McCloskey’s Blueberries for Sal (1948), which has endpapers depicting Sal and her mother canning blueberries. Lin had taken her daughter to an exhibit of McCloskey’s work at The Carle called Americana on Parade, which didn’t feature anyone who looked like them. In modeling her own book after McCloskey’s classic picture book, Lin asserts that Asian Americans are part of Americana.

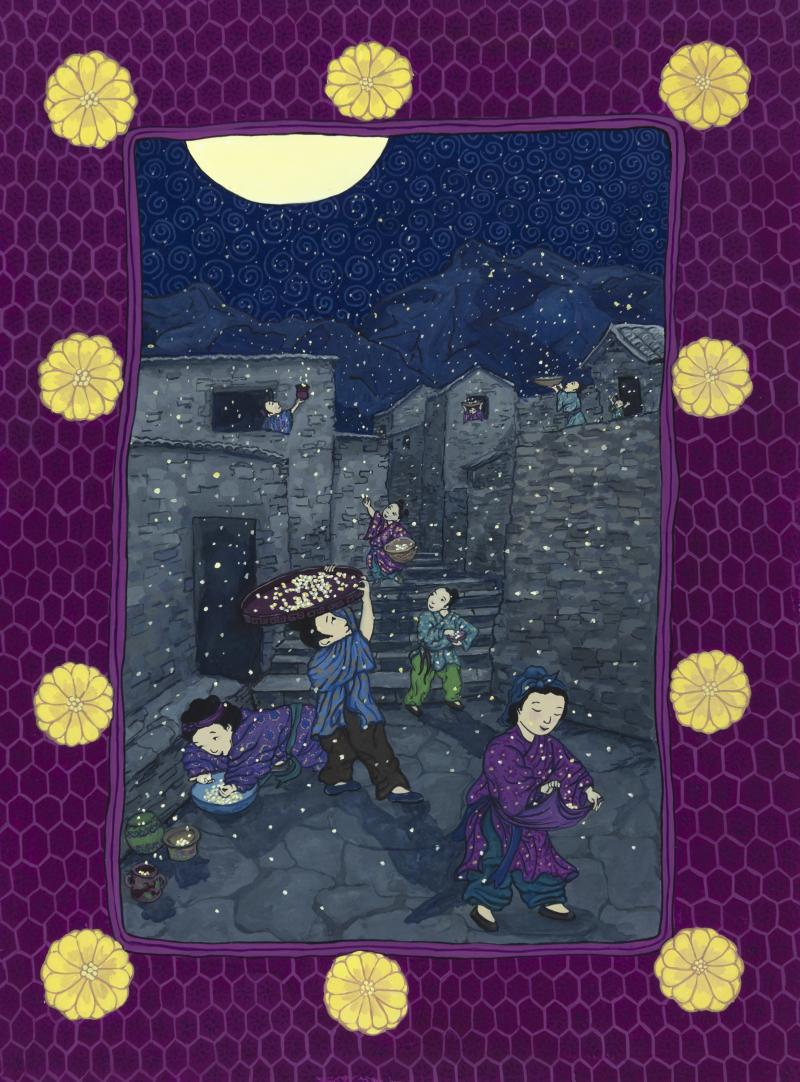

If Lin’s early career was about exploring her Asian identity after not feeling Asian enough, her more recent work, like A Big Mooncake for Little Star, Chinese Menu (2023), and her latest, The Gate, The Girl, and the Dragon (2025), is about exploring her American identity as a diasporic Asian. With many more Asian American authors today than when Lin first started her career, she doesn’t feel the unfair pressure anymore to represent all Asian Americans, a mark of progress towards narrative plentitude.

“I feel like now, I want to claim the American side—but as an Asian,” she says. “Instead of just Asian identity or American identity, it’s about Asian American identity for me.”