Nura and the Enigma of Childhood

Why is Nura Woodson Ulreich (1888-1950) so little-known today—if at all? She was highly acclaimed in the 1930s and ‘40s, then simply went off the radar screen. A recent article in The New York Times about artist Doris Lee (1905-1983), who suffered a similar fall into oblivion, offers a partial explanation: as representational artists, they were overshadowed by the emerging non-representational emotional frisson and energy of Abstract Expressionism.1 Nura, as she styled herself (a nickname given by her husband), died young in 1950, preventing any opportunity to further her career, especially as an author and illustrator of children’s books where she was just beginning to garner recognition. She enjoyed international critical acclaim and a measure of financial success, albeit tempered by the Great Depression, and attracted an impressive roster of collectors and museums that acquired her work. Kendra and Allan Daniel have championed art by illustrators for children for a long time, bolstered by Kendra’s commitment to underappreciated women artists. She was captivated when she first encountered Nura’s art, and together she and Allan committed themselves to reviving her reputation.

When Allan and I were first together, over thirty years ago, we scoured every antique shop that we came across. Many proliferated before the internet took over and they provided a rollicking good time for treasure hunters.

On one of these adventures, I spotted The Fish Boy, a painting signed “Nura” in an unimpressive jumbled shop. The artist’s name was unfamiliar, but the painting struck me as highly inspired, and I noted the impressive gallery labels on the back. I was attracted to the Modernist style reflected in the exuberant colors and bold composition; the painting became the foundation of our Nura collection. For several years, my collecting focus had been centered on early 20th century art by illustrators for children, so this was an appropriate addition. I was further intrigued when I discovered that Nura had written and illustrated eight children’s books between 1932 and 1950.

At the time we first discovered Nura there were dealers and scholars promoting the study and appreciation of children’s books, but few were concentrating solely on the original illustration art. As I had a background in fine art and with original paintings as my primary focus, I saw these illustrations as valid stand-alone works of art. Nura’s paintings were a stellar example and as we collected them one at a time, our appreciation expanded. Then, at one point, we tracked down her estate and were able to buy it in its entirety from the son of a friend of Nura’s who had inherited the art.

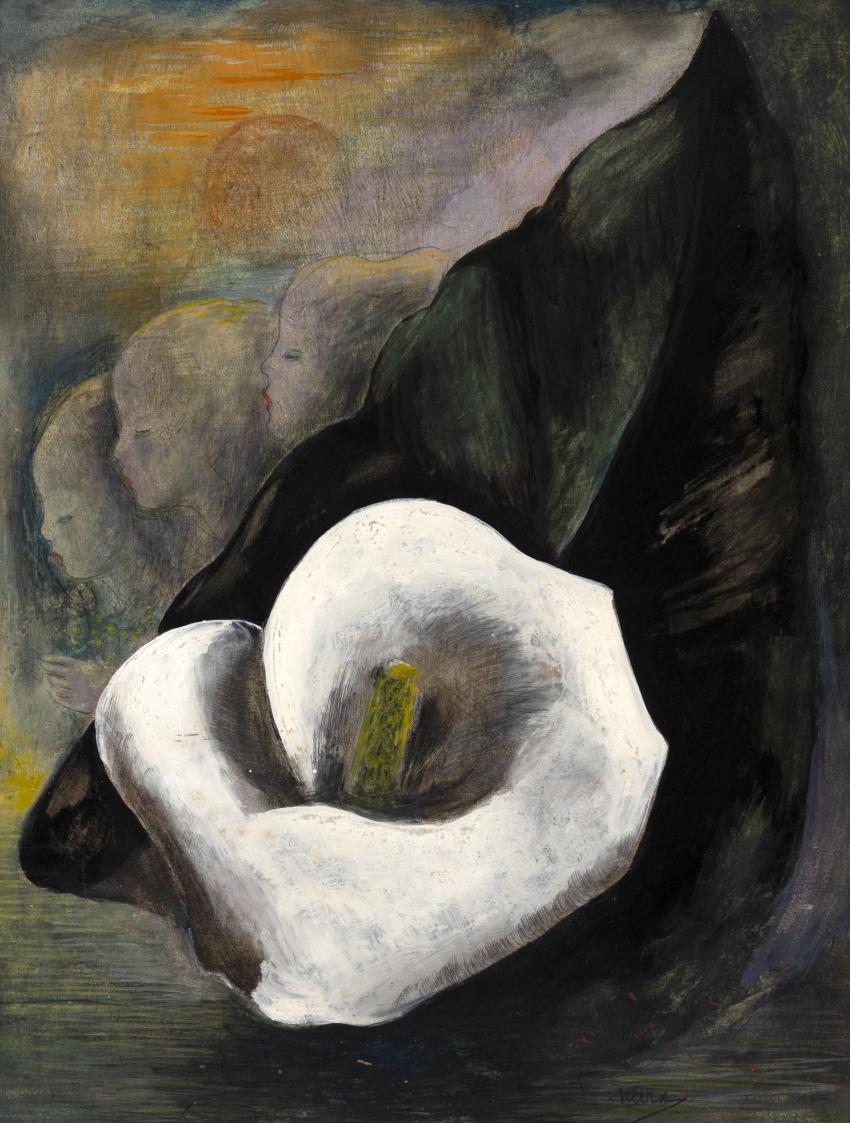

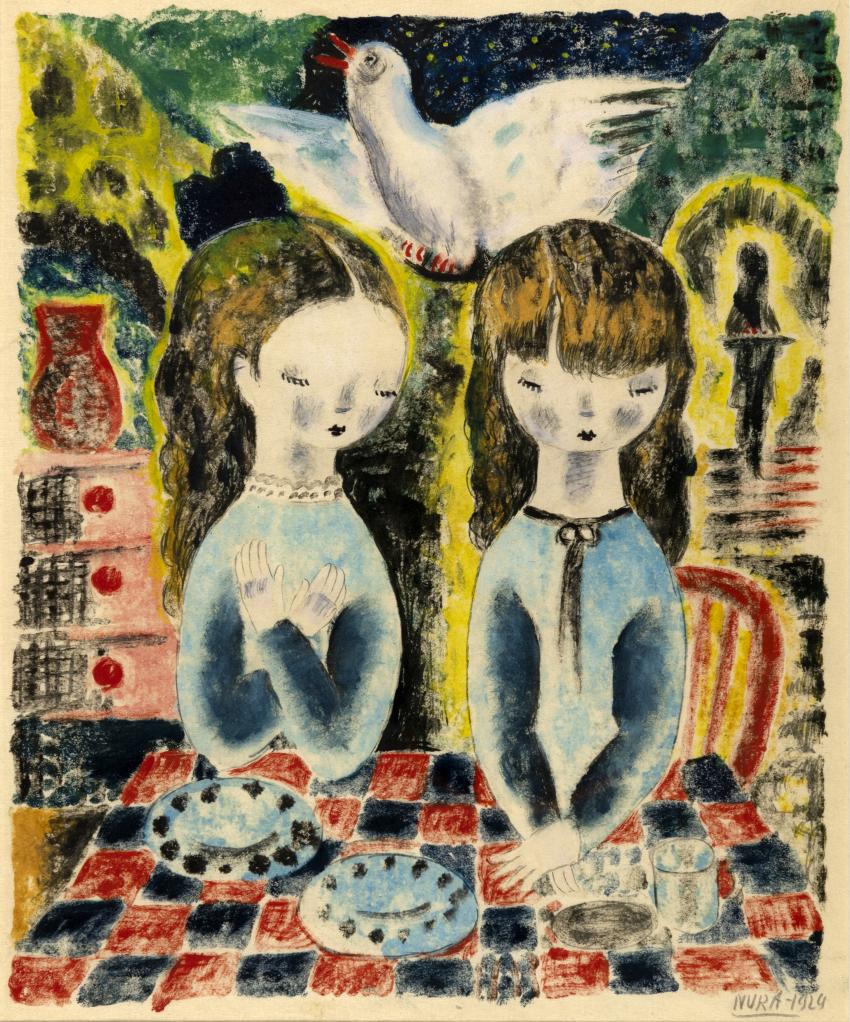

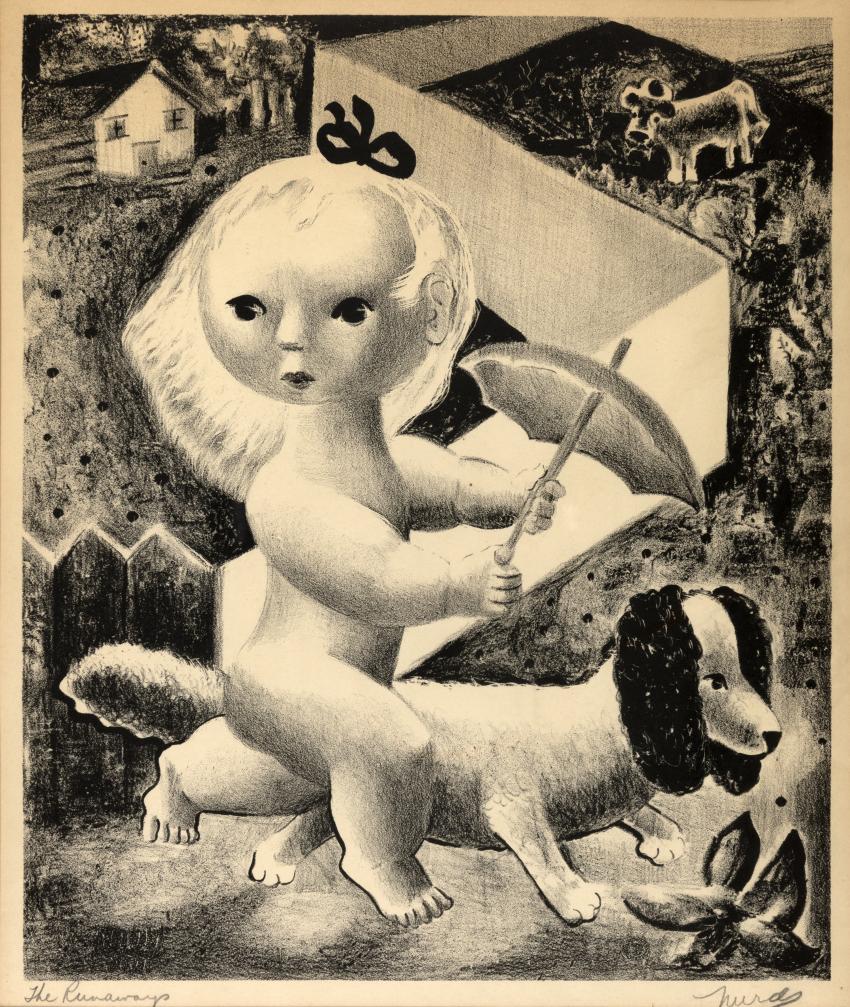

In spirit, the paintings conveyed a celebration of childhood in all its most poignant aspects. Along with her oils and watercolors, Nura produced impressive lithographs, some of which appear in her books. The same charming figures of children that are seen in her independent paintings can also be found in these books, creating a strong link between the two endeavors with their emphasis on whimsical dream-like settings that at times embrace the surreal. In the 1920s, Nura also designed hooked rugs for children’s rooms, incorporating abstract elements mixed with traditional images and later sculpted fanciful terra-cotta figures. We were fortunate to acquire one figure and two rugs, which extended the scope of our Nura collection.

Aside from the Brandywine School of Art, which includes the highly regarded Jessie Willcox Smith and a handful of women illustrators such as Rose O’Neill and Grace Drayton, who saw great commercial success, the popularity of many women artists was not sustained beyond their lifetimes. Nura Woodson Ulreich achieved wide recognition and was often lauded during her career. Unfortunately, this faded with her early demise. We are proud to bring Nura to the attention of the public with these impressive works of art.

—Kendra Daniel

Nura Woodson was born in 1888 in Kansas City, Missouri to Major Blake L. Woodson and Neva Delaney Woodson, early residents of the city and prominent citizens. From childhood, Nura gravitated to art, dazzled friends with her figurative cut-outs, and by 1921 had studied at the Kansas City Art Institute, the Art Students League in New York (taking illustration classes with Frederick R. Gruger and the more prominent John Sloan), and the Art Institute of Chicago. She met artist Edward “Buk” Ulreich (1884-1966) in Chicago, and they were married after a whirlwind romance in December of 1921. Significantly, it was Nura who introduced Buk to the tenets of Christian Science, which played a significant role in their lives and contributed to the underlying spirituality of their art.

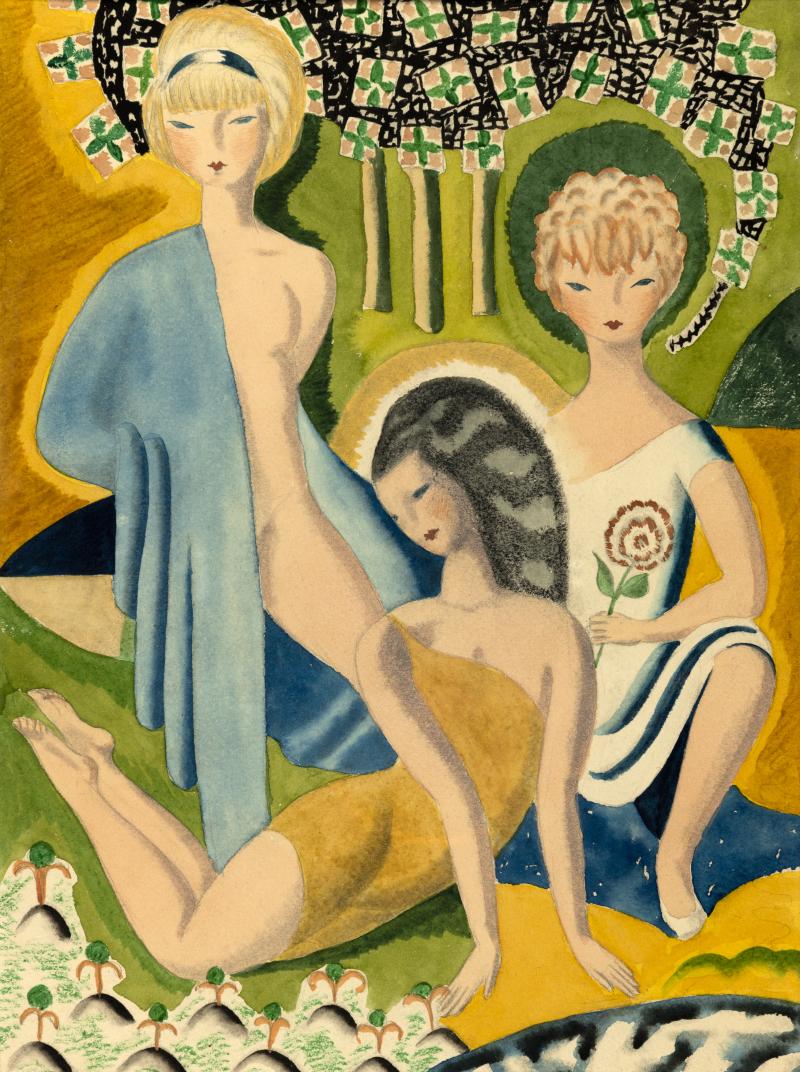

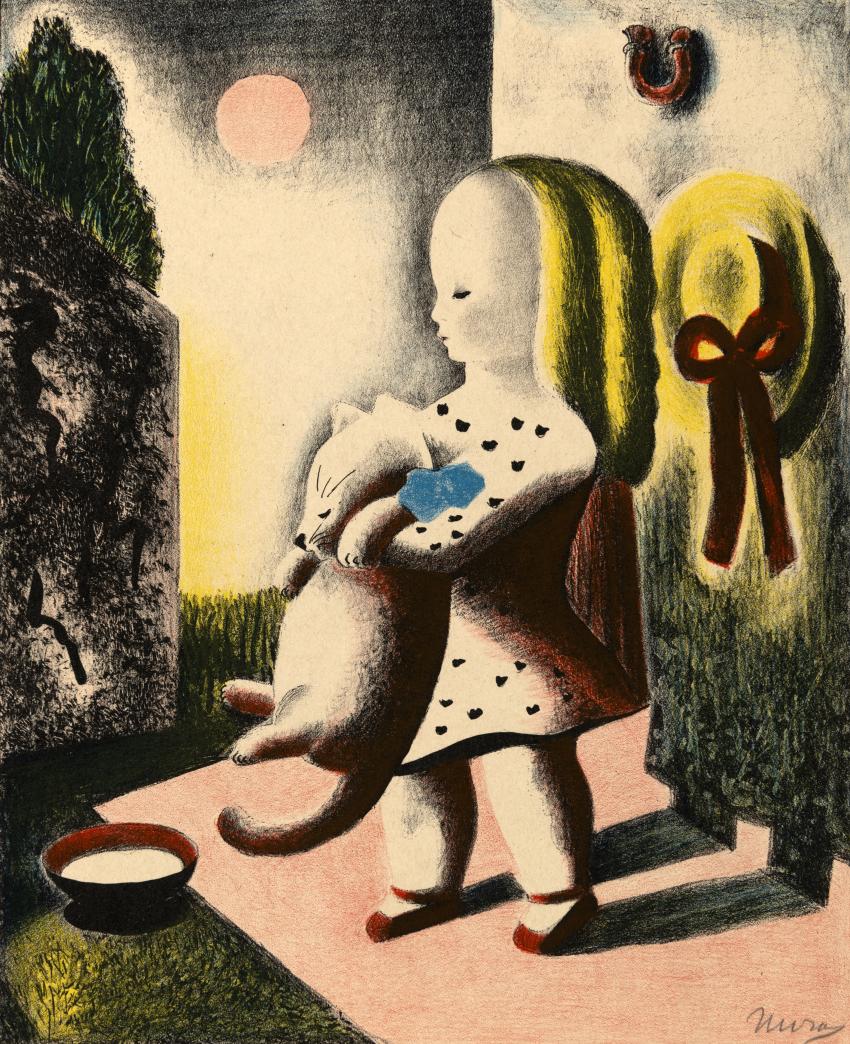

Further validation was their acceptance at the esteemed Salon d’Automne where only thirty-five Americans were included that year in a very competitive submission process—Nura with two paintings and Buk with one. Surviving works by Nura reflect her embrace of modernist trends circulating in Paris, and her watercolors belie the exquisite use of color and sense of mood acknowledged by the Times critic. Additionally, they reveal her admiration for the current Art Deco elements of angular, stylized forms and restrained clarity of design, which had taken Paris by storm with the enormous Exposition des Art Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes exhibition mounted there in 1925. Nura manifests this influence in Tête à Tête, 1927, a watercolor painted after her return to New York. It reflects Nura’s continued embrace of Art Deco. She simplifies the forms to convey a sense of pattern, reinforced by the shallow sense of space. Nura reduces the girls’ and cat’s anatomies to spare geometries. There is no sense of communication, which stands at odds with the painting’s title that indicates an intimate conversation. An equally potent manifestation of her Parisian experience is Fresh Spring Breeze, one of her most complex compositions to date. The intricately patterned geometric window frames two figures and a dog who float in a richly decorative landscape. The figures assume a balletic quality in which their lithe grace emits an otherworldly sense of illusion, itself reminiscent of Marc Chagall, though less ethereal.

Although comfortably situated in Paris, the couple returned to New York in October of 1926, and by the fall of 1927, they were both exhibiting at the influential Dudensing Gallery on 57th Street and received favorable mention in an article in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle about “Talented Unknowns.”3 The author acknowledged they both transcended obscurity, but opined their modern aesthetic rendered them suitable for the adventurous collector. Significantly, the critic, noting the sophisticated and mannered presentation of Nura’s female figures, compared her to the French “moderne” artist Marie Laurencin while drawing important distinctions: “Nura, if lacking Marie Laurencin’s elegance, has spontaneity and vitality and a more flexible quality of design then[sic] the popular French painter.”4

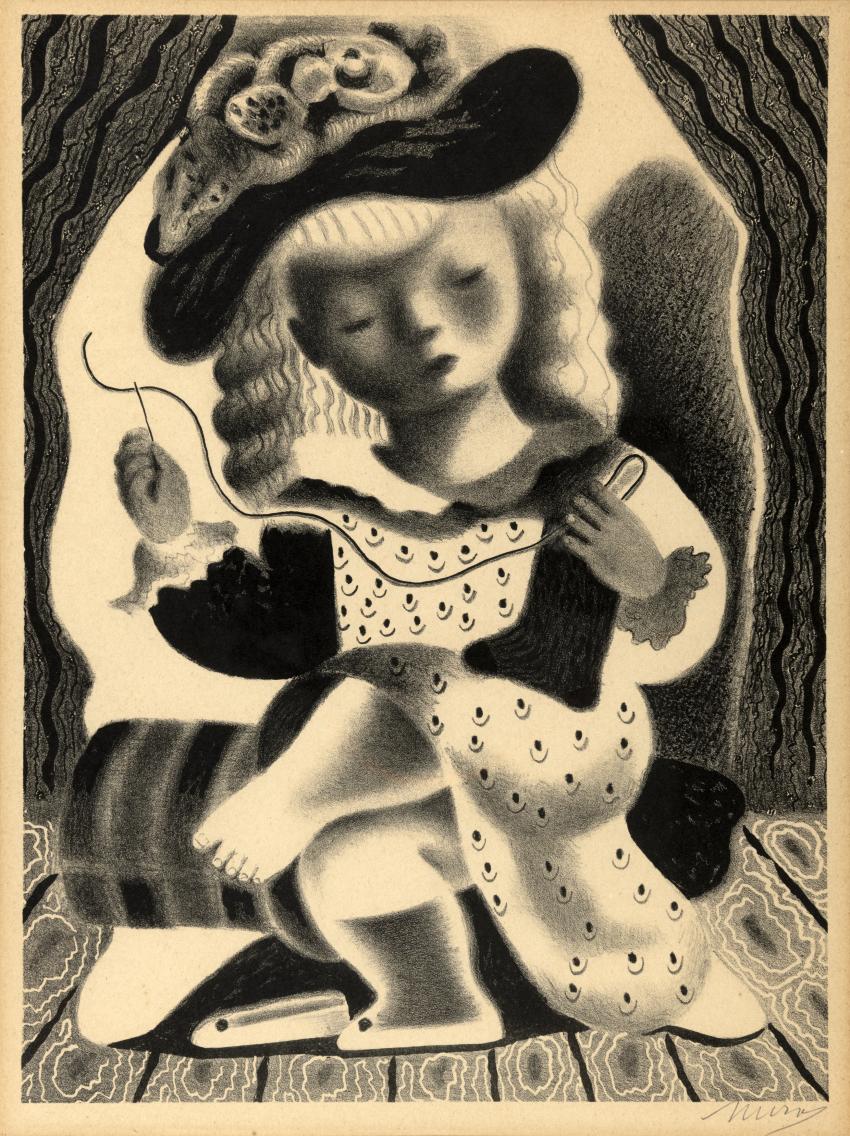

The Great Depression took its toll and in 1932 the Ulreichs, out of necessity, moved to more modest quarters on East 40th Street. Nura often put her address on the back of her paintings, and this has aided immeasurably in dating many of them. For the balance of the decade and the ensuing one, Nura continued to create art in various media, including terracotta sculpture. She also began teaching to supplement their income. Nura’s resourcefulness and pragmatism also emerges through her joining the cadre of highly respected artists creating affordable prints for the Associated American Artists (AAA), established in 1934.9 Why Nura waited until 1946 is unclear; perhaps it was her earlier connection with the contemporaneous American Artists Group or her all-consuming involvement with creating books. She followed her first offering to AAA, Listen (1946), with the lithograph Seraphine Sews in 1947, an exercise in distracted youthful domesticity. Seraphina sits comfortably with her left leg casually crossed over the right. Her sewing is not convincing – it seems more about the sinuous line of the thread than the act of sewing. The smooth, subtle modeling of her features and legs stand in marked contrast to the plethora of pattern encasing her. An explanatory text accompanied each print, providing insight about the artist and the work itself. The text for Seraphine Sews includes the by now well-published rationale of Nura’s preoccupation with the theme of childhood, worth quoting at length:

Childhood is a state of being. Children express it. They do not possess it. It is intact when they enter it and intact when they leave it. It is not confined to flesh and blood children. Whatever invokes within us gentleness, tenderness, or a desire to both laugh and cry is surely imbued with the Childhood Spirit. The little figures in my works are offered merely as symbols of the universally beloved state being called childhood.

—Nura Woodson Ulreich

Nura created two additional prints for the AAA in 1948, and at $2.50 per image, they were eminently affordable—part of the Association’s mission.

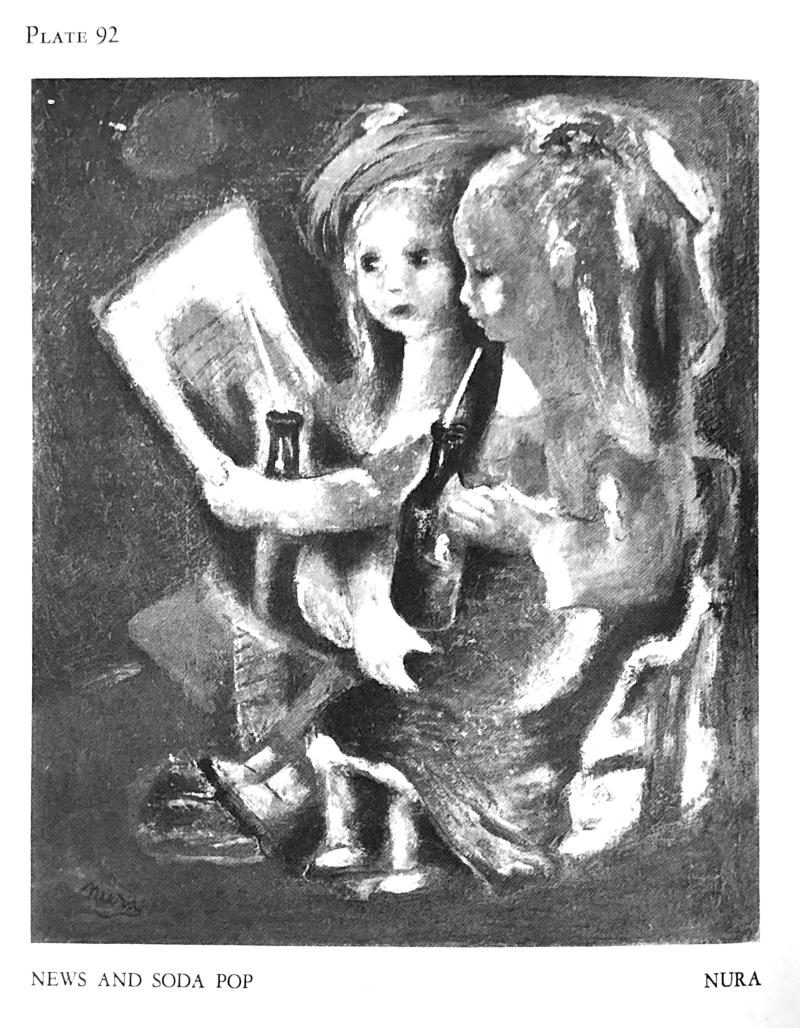

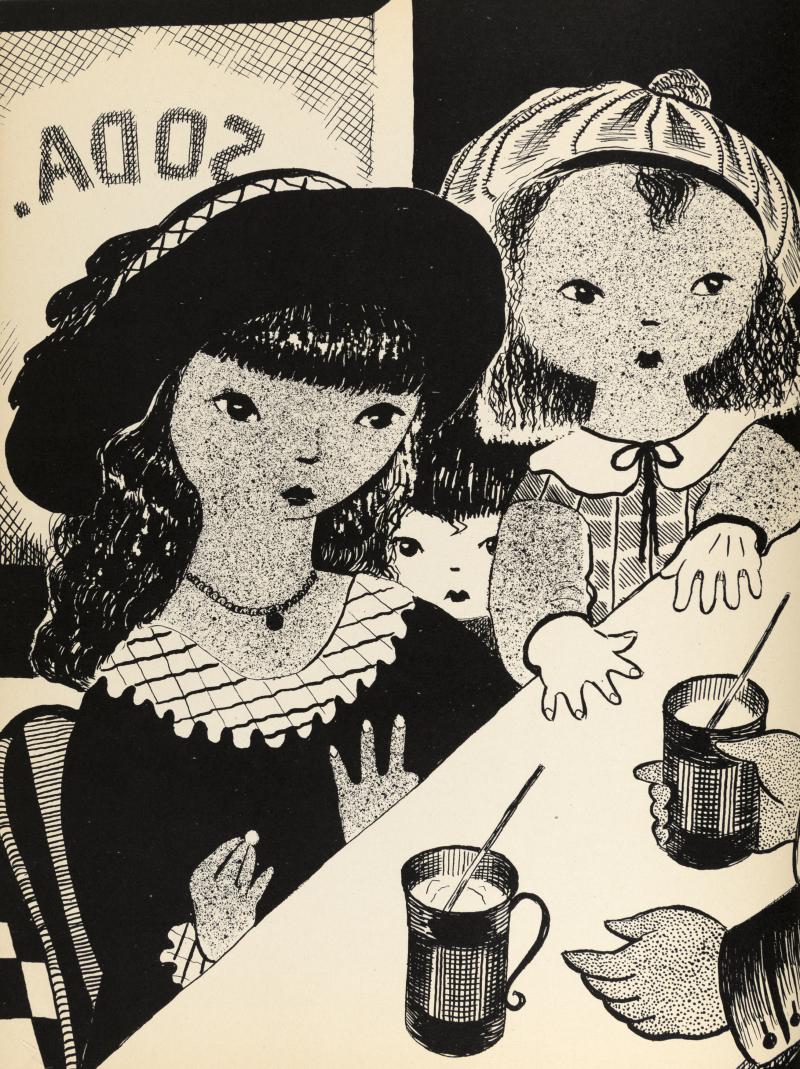

One of Nura’s culminating triumphs was inclusion in The Carnegie International in 1949 with a painting titled News and Soda, itself a throwback to an image in Stories. Initially exhibited at the Ferargil Galleries, one of Nura’s patrons, Loretta Hines Howard, acquired the painting and subsequently agreed to lend it to the Carnegie. The painting also graced the cover of the May issue of Art Digest, where Nura’s art was described as, “paintings of absurd children living in a dream world [that] have charmed a limited but loyal audience for over twenty years.”10

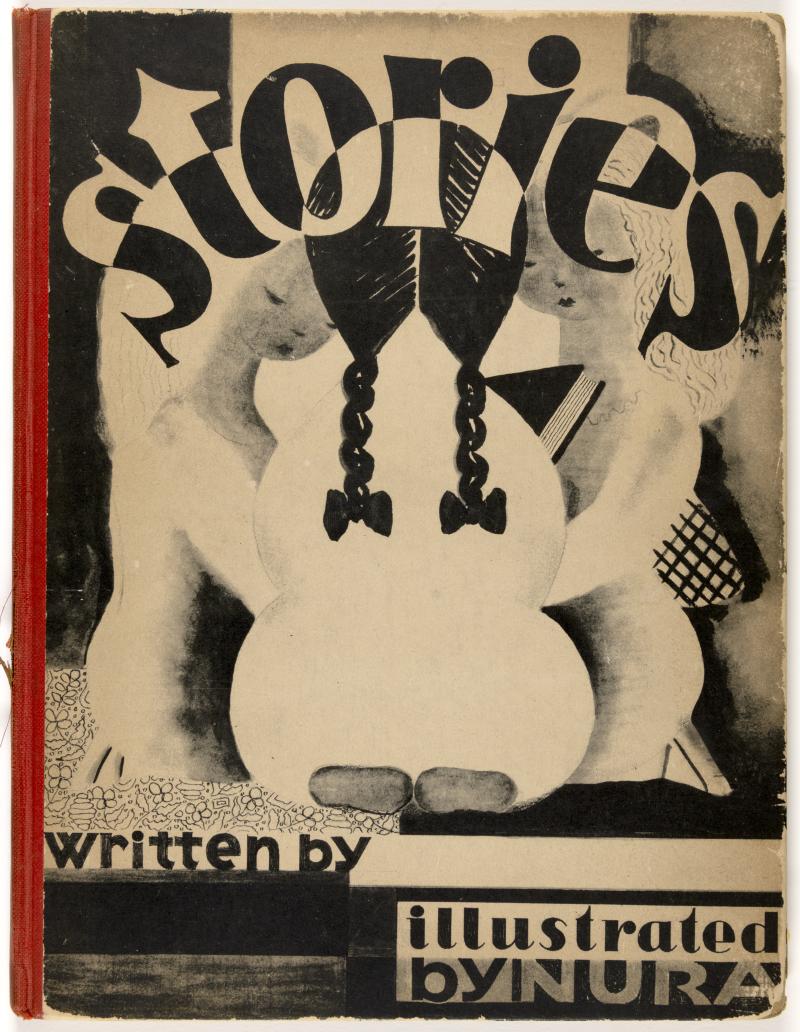

As her artistic star continued to rise, so, too, did Nura’s picture book career, which had begun in earnest fifteen years earlier. The Great Depression adversely affected so much, including a collapse of the art market. Consequently, Nura, realizing a latent desire, turned to creating children’s books, meeting her need for a reliable source of income. For her first book, Stories (1932), she collaborated with the well-known textile designer Marguerite Mergentime, whom she had met during her time designing hooked rugs. They presented their unique story idea to several publishers who rejected them, citing a lack of commercial viability, presumably aware of the lukewarm response to Mary and Edward Steichen’s innovative First Picture Book (1930), which had paired Steichen photographs opposite blank pages. Consequently, they self-published the book, employing the highly respected designer Robert S. Josephy to oversee its production.

Nura’s second book, The Buttermilk Tree (1934), took its inspiration from her sister’s love of buttermilk—so much so that her mother joked she would have to grow a buttermilk tree. Artistically, Nura persisted in her highly demanding, all-encompassing production standards, even during such economically challenging times. Both text and images are printed on high-quality heavy stock paper. The Buttermilk Tree was privately published; Nura acknowledged thirteen co-publishers—an early example of crowdfunding. Apparently, she distributed a colored lithograph as a token of gratitude, one of which survives and is in the exhibition, Hay Foot, Straw Foot. It is inscribed to Godfrey Plachek of Chicago in appreciation of his investment of $50.

The narrative chronicles a child’s journey from birth to motherhood. The text, with its own dedicated pages, is spare, poetic, and often elusive, paralleling the equally enigmatic visual complexity of the imagery. For example, “the time” (at the outset of the book) comprises a densely packed composition containing figurative elements that fluctuate between the benign—an anthropomorphic crescent moon in the foreground and thirsty sheep/rams drinking from an alabaster ewer—to the more ominous fluted horn suggesting an all-seeing eye that hovers in the night sky. Equally disturbing, and an apparent example of shape shifting that Nura often favored, is the drinking sheep/ram in profile at the left whose straight horn becomes a stiletto-like weapon held aloft by a figure suggested in the left outline of the ewer.

The image Age Fifteen provides an acute insight into the angst of adolescence. The by now young woman kneels precariously on the window ledge with her cat, a beloved motif of the artist. The girl’s expression is impassive and remote, lacking emotion and absolving her—as with all Nura’s children—from the saccharine cuteness associated with childhood. The surrounding imagery chronicles vanity—the mirror and brush of the dressing table; secrets and privacy—the diary; question marks—self-doubt; and young love—the tuxedo-clad boy in the upper right. These legible symbols counter the more arcane elements spread along the bottom of the composition: the pair of eyes stacked one over the other and the black-silhouetted figures, echoing Nura’s early facility in making cut-out paper dolls.

Reviews of The Buttermilk Tree were favorable, bearing signifiers such as “fanciful,” “delicate,” and “whimsical.” Nura enjoyed significant exposure in a laudatory review in Time magazine whose reviewer called its text “evanescent,” and the pictures, “which achieve charm by combining simple mysticism with an awareness of actuality.”12 This perceptive assessment captured Nura’s single-minded approach in chronicling childhood which, for her, was a state of being rather than a statement of reality. The Buttermilk Tree garnered another American Institute of Graphic Arts award.

From the cycle of life to a day in the life, we move to Nura’s Garden of Betty & Booth (1935). Although Nura continued her production and publishing responsibilities, she secured Wm. M. Morrow & Co., a highly respected publisher, to distribute the book. In an undated letter soliciting financial assistance for the project, Nura talks about the brilliant color and how she works directly on the plates where, “it will be a book of original lithographs in color.”13 Only one review has come to light, significantly in Parnassus, the bulletin for the College Art Association, where most reviews considered scholarly texts. The reviewer called the book, “delightful,” and “an admirable example of the art of lithography and of book design,” noting its appropriateness for adults on this score. He acknowledged the work of the lithographer George C. Miller and concluded, “The combination of artistic ability and publishing enterprise has proved successful in Nura’s case.”14 Other critics continued to praise her work for its honesty, authentic naiveté, and humorous yet elusive imagery.15

The story chronicles Betty’s typically active day, accompanied by her shadow, an intriguing anticipation of Fred Astaire’s legendary dance with his shadow in Swing Time, which premiered the following year. Nura structures the book with a clock face, sun, and moon that move hour by hour to signify the day’s progression. The four winds provide the narrative thread, and the text possesses a hand-printed quality reinforcing a sense of informality. Each hour describes an activity, moving from morning play, chores, and lunch to quiet time, tea, and bed. A mid-afternoon rain shower and its attendant cloudiness briefly evaporates Betty’s shadow, offering a momentary solo interlude for the character.

While the protagonists retain Nura’s penchant for outsize heads and broad facial features, the imagery and text are far more accessible for the young reader than her less obvious imagery intended for older audiences. Forms are flat and simplified to generate a clarity of pattern and design that results in the spatial ambiguity so important to the artist. The mirroring of Betty and Booth’s images/bodies in color and black further provides opportunity for a visual interplay generated through negative spaces. We also begin to see the repetition of motif such as cats, the cow, and a picnic setting, as the artist probes and interprets the world of the young child.

The Silver Bridge, once again self-published, appeared in 1937 and constituted Nura’s most ambitious literary effort to date, approaching a novella in length. Comprising seven extensive chapters, each adorned with a concluding illustration, the book transcends a conventional children’s story. The narrative chronicles the hardship and survival of frontier life and resonates with Laura Ingalls Wilder’s “Little House” books that began appearing in 1932 to great acclaim; happily, Nura’s text is devoid of the racist attitudes of Wilder’s viewpoint.

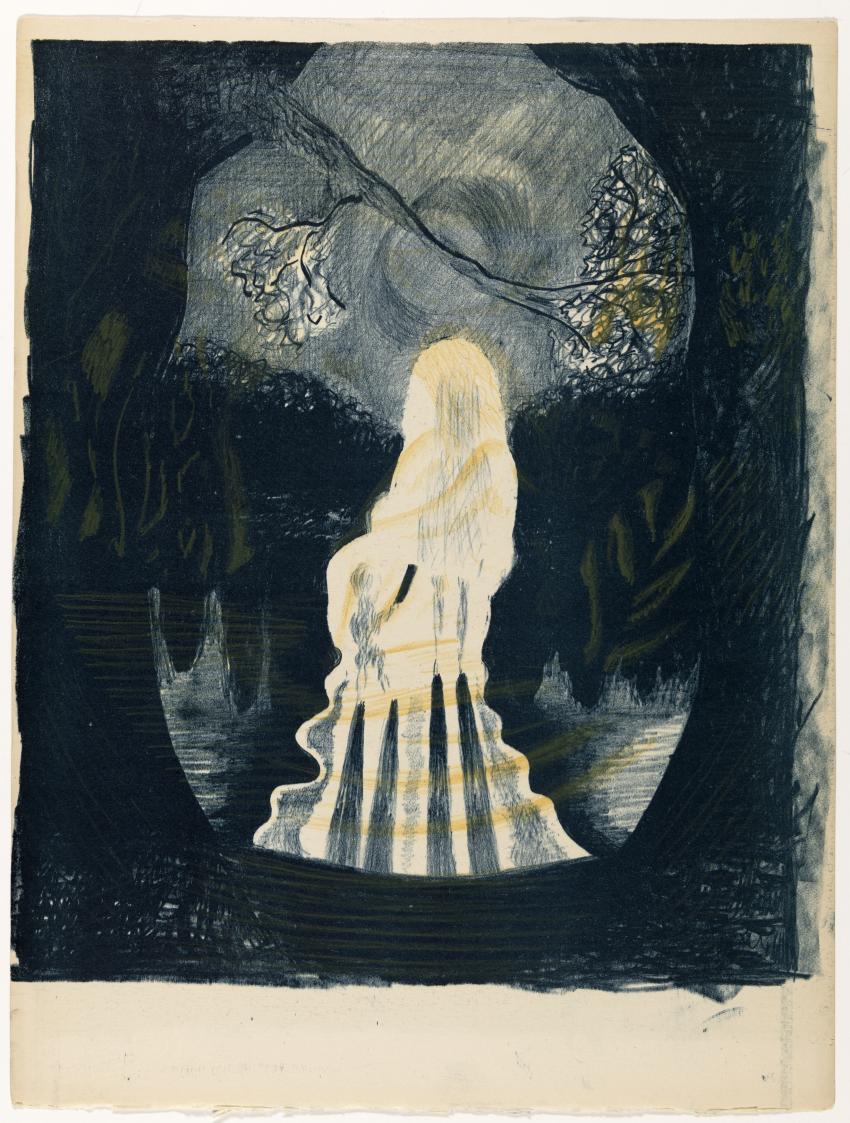

Nura continued to employ color lithography and provides a departure from her previous efforts in its painterly execution and broad palette ranging from delicate pastel hues to darker, more foreboding colors. Also, the rendering of the figures stray from Nura’s predilection for gentle distortion and reinforce the veracity of the narrative. And yet, enigma permeates, and recalls artists such as Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon, who were part of the Symbolist movement of the late 19th century. Poverty and hardscrabble survival vie with the mysterious sense of hope embedded in the motif of the silver bridge. Is it a conduit to the resolution of dreams and fulfilled aspirations, or is it a glorious pathway to “the promised land?” The concluding image of chapter three depicts Rose, the eldest child, and her youngest sister Tulip entering the river in a delineation that closely captures the text, and, to Rose’s astonishment, the infant Violet can walk on her own. The aureole of golden light and shadow that encase the two girls underscores the sense of mystery and ambiguity. Despite the long shadows their legs cast, a duality between the two– and three-dimensional persists, providing a measure of abstraction, literal and figurative. Any sense of release or earthly salvation is compromised by the final sentence of the chapter, where baby Violet in her tiny voice assures her sister, “Rose is my shepherd, I shall not want.” This paraphrase of the 23rd Psalm signifies the verse as a staple of funerals and memorial services.

One unnamed critic commented on the high standards and sophistication of Nura’s books observing, “She writes, illustrates, designs and publishes her own books, which are chiefly for the libraries of collectors and art museums,”16 while the reviewer for Parnassus continued his praise of, “another item in a brave and charming series,” and extolled not just the color illustrations but the typography, “original but in excellent style,” and concluded, “the book is likely to be purchased by collectors two copies at a time, one for pleasure and one for profit.”17 Nura must have appreciated the praise and sense of promise, but likely remained equally frustrated by the lack of commercial success.

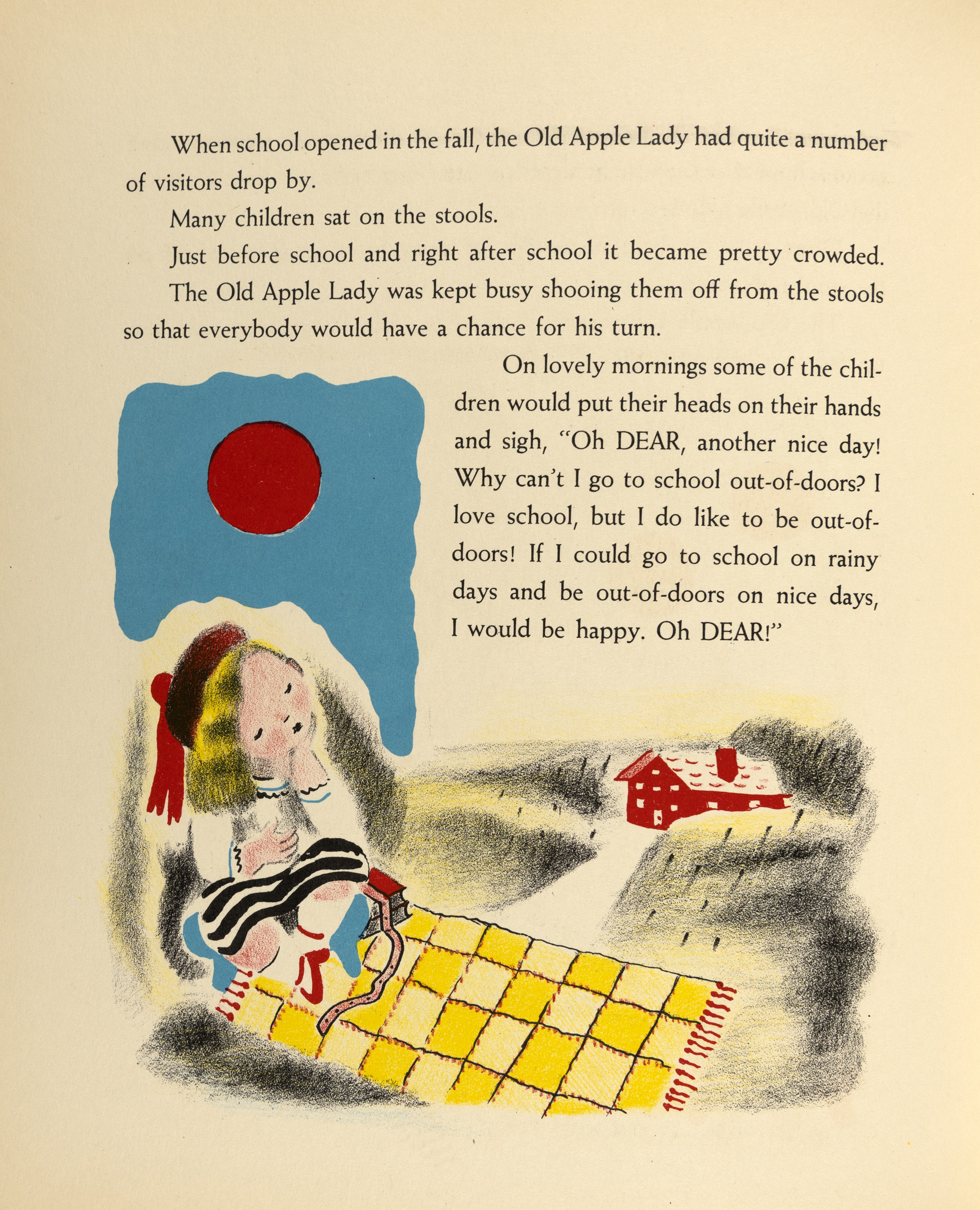

A six-year hiatus ensued in Nura’s children’s book ventures, and when she resumed, she had attracted a publisher, Studio Publications, Inc., a relatively new enterprise focused on the arts and demonstrating high production values. Nura also pivoted to more accessible content for young children. Nura’s Children Go Visiting (1943) recounts the story of a lonely grandfather who invites all twenty-six of his grandchildren to visit, and, to his astonishment, they all accept. The artist creates less stylized figures, making the settings more plausible to the youthful eye, and employs a delicate, soft, granular texture that was in favor at the time.

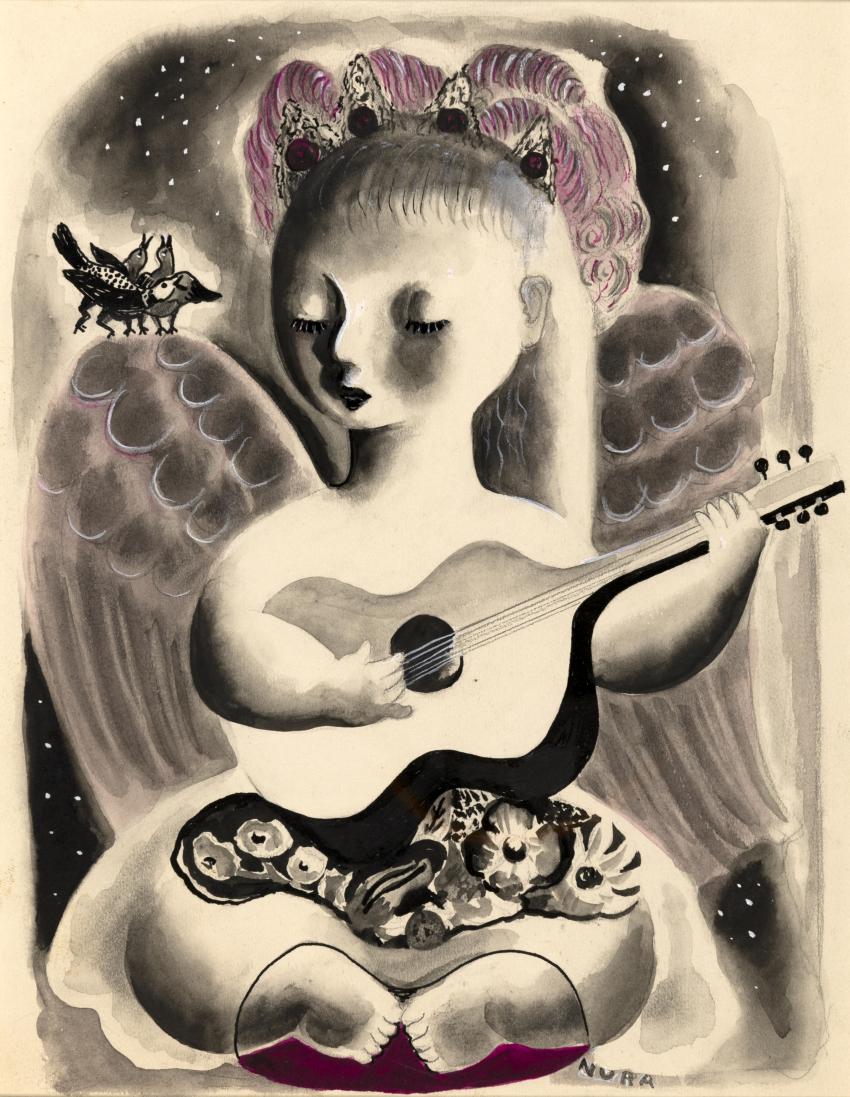

The American Artists Group also commissioned artists to design Christmas cards, for which Nura created Harmony in 1941. The depiction of a celestial angel playing a guitar accompanied by a chorus of small birds constituted a slight variation of an even earlier watercolor Nura had exhibited in 1935.19 The artist tightened her free handling to enhance the legibility of the card. In the final iteration for the book, she made further, subtle, and not-so subtle refinements, most notably the color scheme, which morphed from purples and black of nighttime to more joyous pinks, yellows, and reds, juxtaposed with the cerulean blue sky of daytime. The uplifting result underscores Grandfather Brown’s happiness at no longer being lonely.

Newspapers around the country continued to comment on Nura’s activities, including assessments of her books. These articles were invariably complimentary and often noted that many of the images from the books were available as original works available for purchase. Several persisted in touting Nura’s bright future as a highly desirable artist to be collected.

Studio Publications was sufficiently pleased with Nura’s Children Go Visiting that they agreed to publish her next book, All Aboard We Are Off (1944) the following year and affirmed this decision with a commitment to a generous use of color illustrations. According to the copyright page, Nura lithographed the drawings directly on the stone which were then printed in four colors by the expert printer George C. Miller—signaling an ongoing premium on quality.

Nura, in the art and format of All Aboard, continued to gravitate towards the mainstream of convention. The story, while fanciful, is readily comprehensible, and the illustrations avoid the otherworldly. Significantly, Nura begins to integrate image and text in the design of the book. It graced several recommended lists and was judged in one review as “another of Nura’s rollicking books in which a large group of children have marvelous adventures in pleasant text and marvelous illustrations.”20 Of equal import, the Montclair, New Jersey paper reported that Nura was leaving her teaching position at the Montclair Art Museum because of extensive work commitments in New York. This would suggest Nura had achieved a degree of financial stability to warrant giving up the security of a paid job.

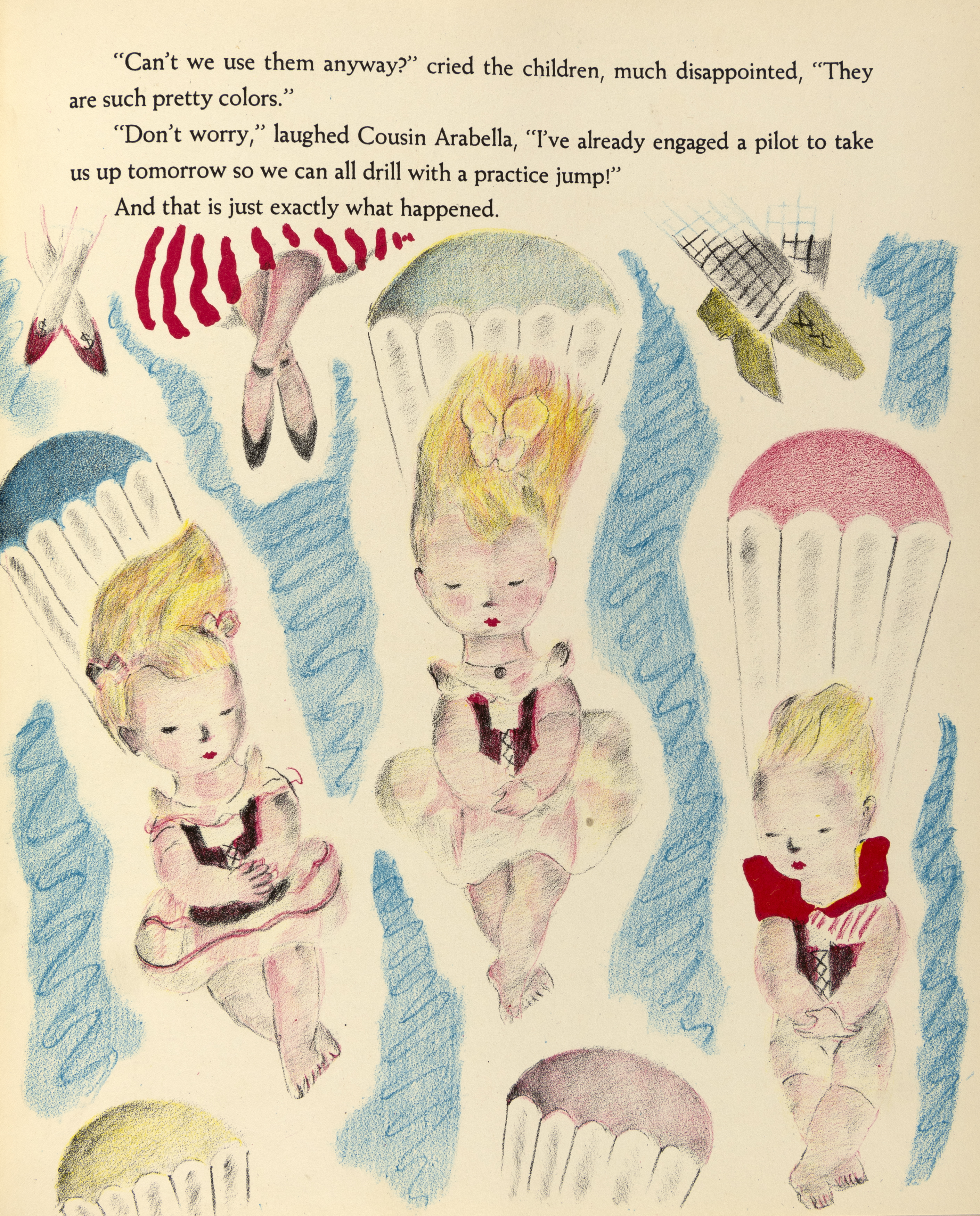

Belt-tightening still cast a shadow over the post-War euphoria where the nuclear family was paramount. In The Mitty Children Fix Things (1946), Nura spins a tale of the Worthington Mitty family (is this a sly reference to James Thurber’s “Walter Mitty” of 1939?) who confront the dilemma of tolerating a wealthy but critical cousin, Arabella, for financial support. As the story unfolds, the five Worthington children demonstrate sufficient initiative and self-reliance to persuade Arabella that the family merits her generosity. Arabella concurs and, in an acknowledgement of female independence, takes the children up in her airplane (think Bessie Coleman, Amelia Earhart, and other adventurous women). In the concluding episode, she hires a pilot, so that she and all the Mittys can have a parachuting experience considered by one reviewer, “a perfect ending to a good story.”21

In ongoing recognition of Nura’s reputation, The Junior Literary Guild and American Studio Books published The Mitty Children Fix Things and, as with All Aboard, Nura continued to integrate text and image, employing both black-and-white and color illustrations. As with her previous book, the drawings were lithographed directly on the stone and again printed by George C. Miller. Nura continued with a soft, granular quality resonant with such contemporary illustrators as Virginia Lee Burton, Ruth Chrisman Gannett, William Pène du Bois, and Lois Lenski.

Not only were the reviews for The Mitty Children Fix Things universally positive, but at least two were in major New York publications—the New York Herald Tribune Weekly Book Review and The Saturday Review. The reviewer for the Herald Tribune called the book “charming,” and the writing filled with “fancy and humor.”22 Mary Gould Davis, writing for The Saturday Review, judged it a “big beautiful picture book,” observing, “Only Nura could have written it and drawn the enchanting pictures.”23 Assuredly, Nura was finally gaining her bona fides as an established author-illustrator.

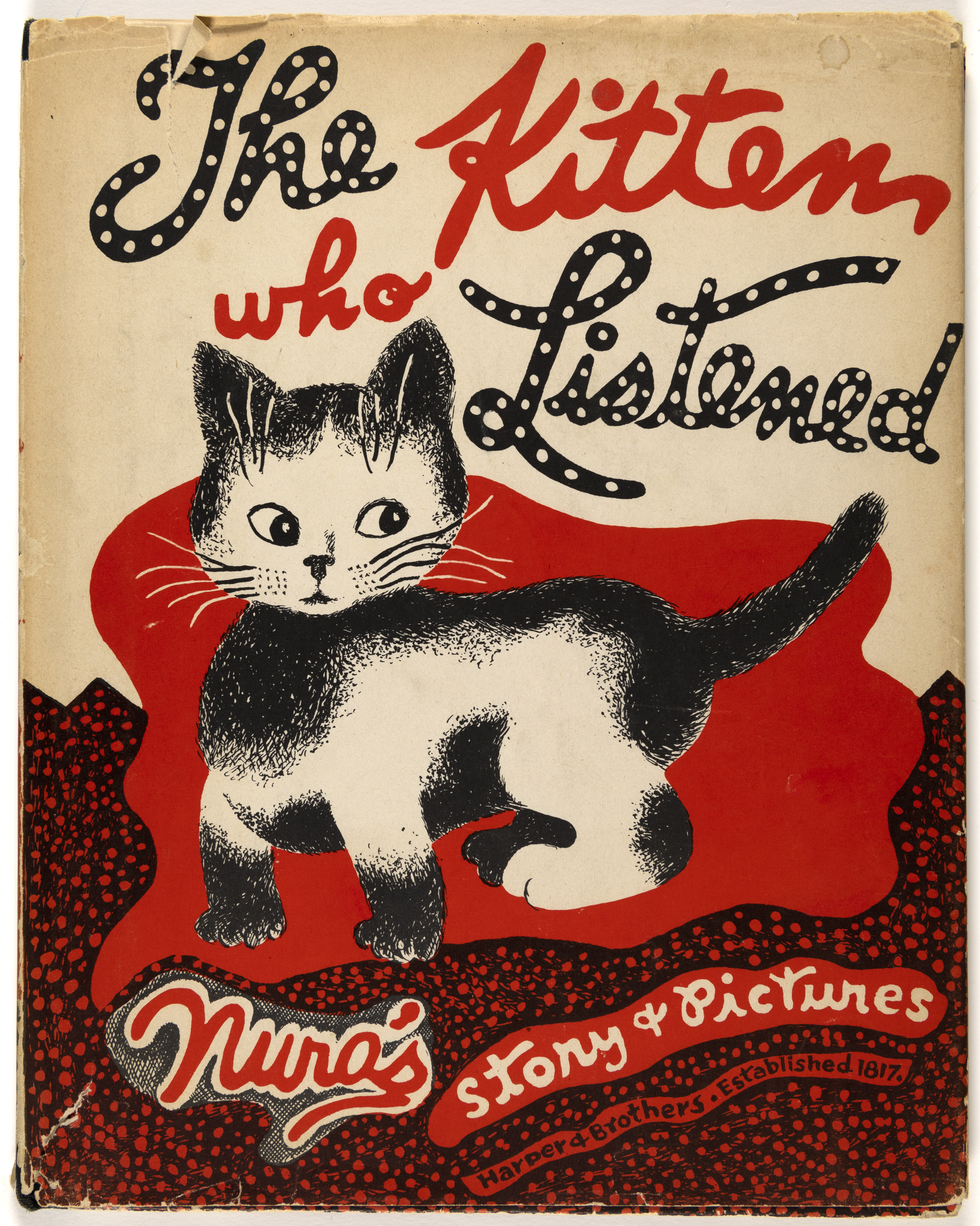

This burgeoning recognition resulted in the legendary publisher Harper & Brothers accepting her manuscript for The Kitten Who Listened, published in 1950. Tragically, this would be Nura’s last book due to her death in the fall of that year. Right from the cover, with its eye-catching image and playful script, the book exudes whimsicality. For the first time, decorative endpapers appear, reflecting Nura’s sustained love of pattern and design. The narrative embraces the “chain” or cumulative format—in this instance what the orphaned cat should be called—and builds in complexity reminiscent of such durable nursery rhymes as The House That Jack Built. Each protagonist, from the colossal Mr. Levering, a coal miner, to the “angry neighbor Brown” has a strong opinion about the cat’s name. Each announces their idea to no response from the cat, and it is only when Cousin Emma strings them all together—eight separate names in ninety-three letters—that the kitten finally responds.

Stylistically, Nura shifts from the soft-focus, granular approach of her previous books to a denser, more dramatic shading where she defines the figures and accessories with an agitated yet precisely rendered black-ink line. She accords each character three-quarters of a page of text set over a descriptive vignette with a full-length portrait on the facing page.

Nura continued to garner critical praise for all aspects of her art, especially her decorative-arts efforts and books. The fall brought notice for The Kitten Who Listened from the influential Horn Book Magazine that called it “amusingly original” with “distinguished pictures in black and red,” making it “a treasure both for children and for Nura collectors.”24 This prestigious arbiter of children’s literature subsequently selected it as one of the best books of 1950.25 Equally prominent, The Chicago Tribune published a review just three days before Nura’s death that lauded its “hilarious solution [that] pleases everyone, including the ageless audience for this beguiling picture story by the talented Nura. Cat lovers from four on up indefinitely [sic] will have to add this to their cat bookshelf.”26

Fate dealt Nura a cruel hand when she died on October 25, 1950, after a lengthy illness. There were prominent obituaries in The New York Times and The Art Digest, but perhaps most eloquent and touching were the words written by Buk in a letter to his family, “Nura was blessed with many friends and was a great gift from God. She had a gift for creative expression that was divine, more than most people know. To our human sense we wish she could have continued with us.”27

Nura was clearly on a path to greater success and prominence as an artist and creator of children’s books. She shrewdly grasped the forces of the market and altered her approach to one that was more readily grasped by young audiences and, of course, parents. The decade of the 1950s brought renewed prosperity to America, and one can only wonder how Nura would have fared in this improved climate. Unquestionably, the advent of Abstract Expressionism and other radical artistic approaches dealt a serious blow to the practitioners of representational art. Sadly, Nura was one of these casualties, and it is appropriate that after more than seventy years she gain some of the respect she is due.

1 Meredith Mendelsohn, “Doris Lee, Unjustly Forgotten, Gets a Belated but Full Blown Tribute, The New York Times, January 2, 2022, p. AR15.

2 Ruth Harris Green, “Autumn Activities in the Paris Art Galleries,” The New York Times, November 21, 1926, p.?

3 Anon., “Talented Unknowns,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 11, 1927, p. 64.

4 Ibid.

5 Anon., “News and Views on Current Art, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 18, 1927, p. 6E.

6 Cynthia Fowler, Hooked Rugs, Encounters in American Modern Art, Craft and Design [Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, Limited, 2013].

7 Anon., “Nura’s Naïve Kiddies,” The Los Angeles Times, November 30, 1930, p. 41.

8 Anon., “Beaux Arts,” The San Francisco Examiner, November 30, 1930, p. 55.

9 Elizabeth Seaton et al., Art for Every Home, American Associated Artists, 1934-2000 [New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015]. This organization should not be confused with the American Artists Group established around the same time and with which Nura was also connected—especially her Christmas cards.

10 Margaret Lowengrund, “Nura’s Present World”, The Art Digest, Vol. 23, No. 15, May 1, 1940, Cover and p. 15.

11 Jane Corby, “IT TOOK AN AMERICAN WOMAN TO THINK OF THIS,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 15, 1932, p. 12.

12 Anon, “Art: Buttermilk Tree,” Time, Vol. 24, No. 11, September 10, 1934, p. 34.

13 Nura to Sue Moody White, undated [ca. 1935], typed letter, Kendra and Allan Daniel Collection.[tk]

14 Philip A. McMahon, “Nura’s Garden of Betty and Booth,” Parnassus, Vol. 7, No. 6, November 1, 1935, p. 30.

15 E. C. Sherburne, “Recent Work by ‘Nura,” The Christian Science Monitor, December 17, 1935, p. 12. This article was a review of Nura’s exhibition at The Arden Gallery in New York, a display of oils, watercolors, and sculpture.

16 Anon., “In the Gallery: News and Views of the Week in Art,” The Kansas City Star, September 17, 1937, p. 28. On the occasion of Nura publishing her 4th book.

17 Philip A. McMahon, “The Silver Bridge,” Parnassus, Vol. 10, No. 4, April 1, 1935, p. 36.

18 Anon., “Works of Art on View During the Current Week,” The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 18, 1927, p. 6E.

19 Anon., “`Childhood Spirit,’ Nura’s Exhibition Theme,” The Art Digest, December 15, 1935, p. 11.

20 Wilma K. McFarland, “Christmas Books Have Titles for Tots, Teen-Agers,” The Knoxville Journal, December 3, 1944, p. 35.

21 Mary Gould Davis, “Books For Young People, Advice from Dr. Newbery: The Five J’s,” The Saturday Review, June 15, 1946, p. 42.

22 Anon., “Tales With Pictures and Songs: The Mitty Children Fix Things,” New York Herald Tribune Weekly Book Review, May 19, 1946, p. VII 10.

23 Davis, “The Five J’s, The Saturday Review, p. 46.

24 Anon., “Nura, Author-Illustrator, The Kitten Who Listened,” The Horn Book Magazine, Vol. XXVI, September 1950, pp. 370-71.

25 “Horn Book Fanfare,” The Horn Book Magazine, Vol. XXVII, July-August, 1951, p. 244.

26 Polly Goodwin, “The Kitten Who Listened, by Nura,” the Chicago Tribune, October 22, 1950, p. 222.

27 Katherine Burkhardt, “Edouard Ulreich: A Retrospective, The Evolution of a Modernist,” unpublished paper, 2004, p. 24