Keeping Up with Ed Emberley

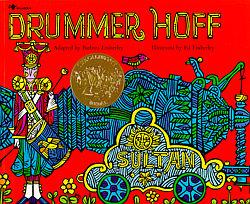

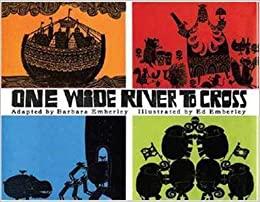

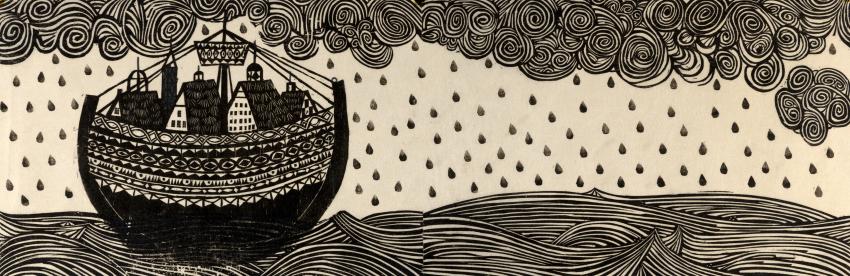

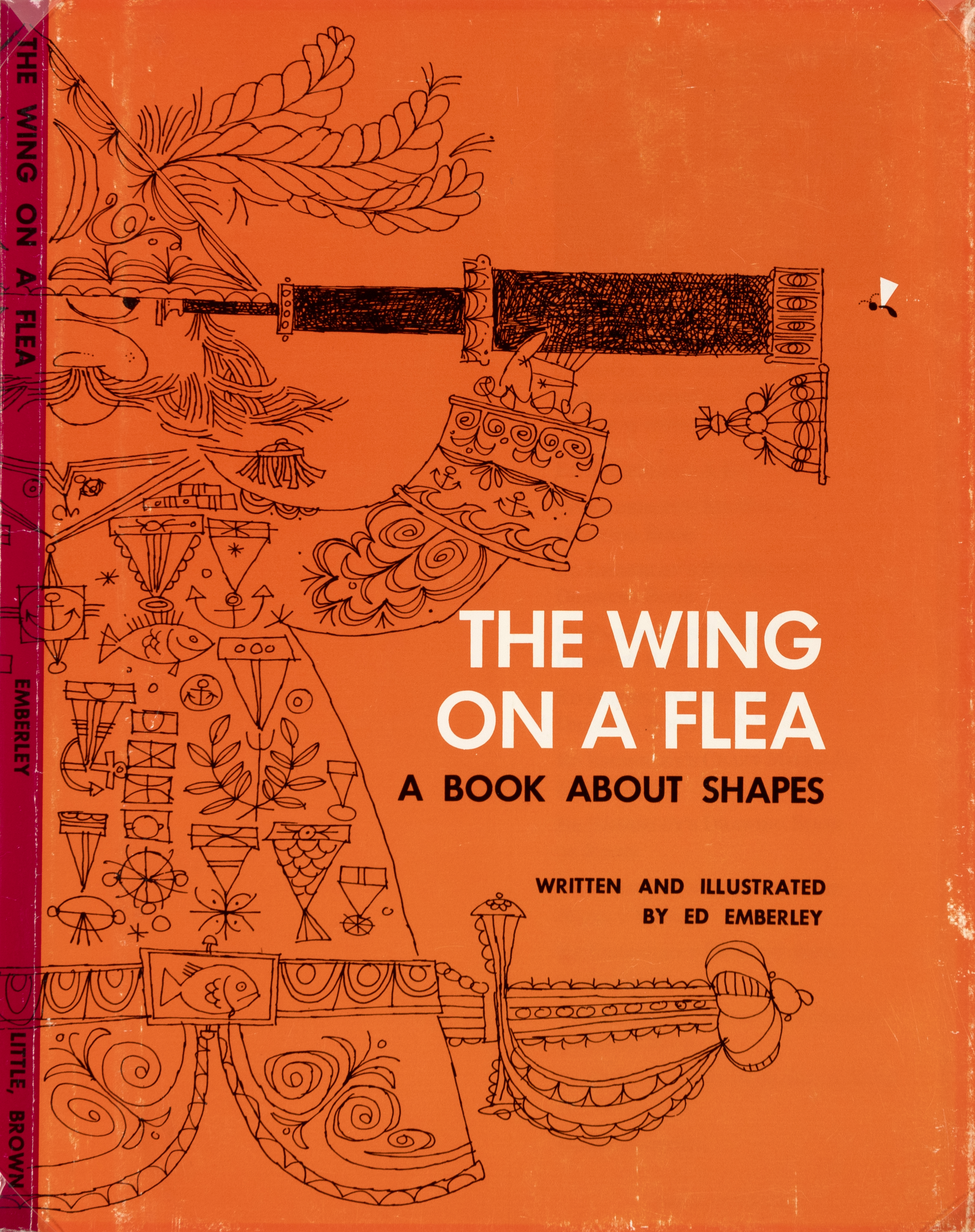

Ed Emberley knows his artistic limitation is boredom. “I love Peanuts and Charles Schulz,” he’s told me many times, “but I just couldn’t imagine sitting there and drawing Charlie Brown 10,000 times.” Emberley knew this about himself early on: he could draw all day long, but repeating himself drove him crazy. From the outset of his career in 1961, he has made children’s books in a variety of different styles and media. His first decade of bookmaking featured a scratchy line–drawing style with screen printing effects (The Wing on a Flea and The Parade Book). Then he explored woodcuts (Paul Bunyan, One Wide River to Cross, and Drummer Hoff), followed by a series with a formal historical style of drawing. He made books on a letterpress (Cock-a-Doodle-Doo), and others using improvised printing blocks (Simon’s Song). And more.

Emberley lives with the insecurity that his artistic detractors would say “he’s just looking for a style.” But once you observe the variety of his work, you will be glad that Emberley bores easily, because he’ll never bore you. Come see this exhibition (and bring friends!), or trawl the rare-book seas to track down as many of his 100+ books as you can (good luck!). You can even get yourself a copy of the big coffee table book, Ed Emberley, that Todd Oldham and I did a few years ago (it’s very nice!). The hardest part about being an Emberley fan is keeping up with him.

Emberley was born in 1931 and grew up in Cambridge in a working-class family with two brothers. His father was a carpenter and handyman who occasionally painted signs, and his mother worked in retail stores. Young Emberley played with the carpenter’s off-cut triangles as blocks and watched his dad draw letters using a grid. There were always pencils and paper around, and Emberley had a knack for drawing. Though there were books around the house, Ed never read much until a copy of The Wizard of Oz in the Cambridge Public Library sparked a love of reading. He attended what is now the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, where he met his life partner, Barbara, who was a fashion design major. He served for a couple of years in the U.S. Army, where he used his sign painting skills to get himself reassigned from digging ditches and other grunt work.

Emberley’s first job was in advertising, which was good practice, but he hated that it was disposable work, quickly glanced at and tossed. Ultimately, he said, “The audience was the trash can.” He decided to freelance and published his first book, The Wing on a Flea, in 1961. While it did well, he realized he couldn’t get by on a $200 book deal each year, so he used his natural creative restlessness to his advantage. While a publisher might print only one book per year, if Emberley switched up his artistic style from book to book and illustrated manuscripts by other authors, he could produce more books per year.

About half of Emberley’s books were written by other people, including adaptations by Barbara. Despite having written so many, he says very little about the process of writing; Barbara had a strong role in that process. Children’s books quickly became a family business. Barbara did the bookkeeping and administrative work—they never used an agent—and she worked directly with her husband in the unseen-but-holy-moly-it-had-to-have-taken-forever work of preparing color separations for press. Their children, Rebecca and Michael, both pitched in and later became children’s book authors and artists themselves. Rebecca was a frequent co-author with her father.

I first met Ed and Barbara Emberley when I interviewed Ed for a magazine article in early 2008. I went to their red house along the tidal shores of the Ipswich River in Massachusetts where they have lived since 1962. The house dates to the late 1600s. (Emberley likes to joke that even George Washington would have thought it was old.) The beautiful original beams in the main “Keeping Room” display the adze marks where they were hand-hewn centuries ago. I banged my head on them, while Emberley kept his head at just the right downward angle. He led me up to his studio, a small front room that in most homes would be a child’s bedroom. And in that room was nearly everything he’d ever made.

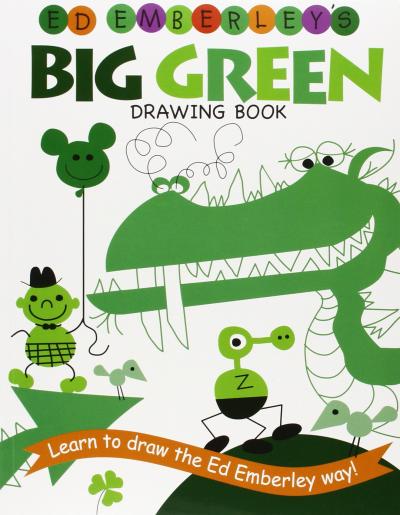

At the time, I only knew of Ed Emberley’s Big Green (or Purple, or Orange, or Red) Drawing Book. Their ‘alphabet’ of shapes and lines were foundational to me as a child. With Emberley’s simple drawing recipes, everyone could draw a dog or haunted house or an alien or alligator. I wasn’t that kid in class who would draw Spiderman. When you draw Spiderman, anything that deviates from the Stan Lee way of doing Spiderman was wrong and everyone could see it. But Emberley’s drawing books don’t privilege flawless reproduction. Everyone—you, me, and Emberley, it turns out—can draw his recipes differently every single time. And they look better that way.

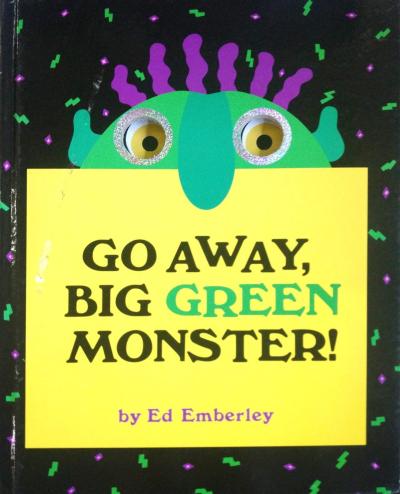

Most of the time, a magazine interview ends with a thank you and a hope to stay in touch, but with Emberley, there was something that called me back. I kept returning to dig through more and more boxes of book artwork and process materials in his small studio room. Gradually I awoke to what made Emberley so unusual and special. While Gen Xers like me grew up thinking the name Ed Emberley was synonymous with his 1970s and 80s Drawing Book series, people a decade older knew him for his 1967 anti-war, Caldecott Medal book Drummer Hoff. And millennials knew Emberley for his 1992 die-cut drama, Go Away, Big Green Monster. Three different best sellers over four decades in three completely different styles and media. Yet, for every one of those books still in print, there are a dozen long forgotten but just as interesting titles, unique in approach and potentially childhood-changing but for the vagaries of the book market.

It must have been a maddening process. Emberley worked on each of his books with diligence, soul, and genuine care. He designed his own books whenever possible, employing beautiful, hand-drawn endpapers, dust jacket end flaps, and hand-lettered his text, glyph cues, colophons, and so on. After he submitted the work, however, it was just a roll of the dice. Publishers could fail him by cutting down on production and printing costs, or the book might not get reviewed or gain traction with libraries, or it may have been so different from other Emberley books that readers would turn up their noses. Ten thousand copies and six months later, some of Emberley’s favorite picture books were out of print, and good luck to anyone wanting to find them again.

Sometimes, though, that disappointing process led to good things. Emberley’s follow up to his Caldecott Medal winner Drummer Hoff was Suppose You Met a Witch. Emberley labored on this incredible guitar solo of a book for years, even making trips to England to draw the landscape—old bridges, stone walls, and bushes—and get it just right. In the meantime, to appease his publisher’s desire for a new title, he knocked out Ed Emberley’s Drawing Book of Animals in a couple of months. You can guess the rest: Suppose You Met a Witch quickly went out of print and you’ve probably never heard of it, while you were likely one of the millions of children who had and loved Drawing Book of Animals.

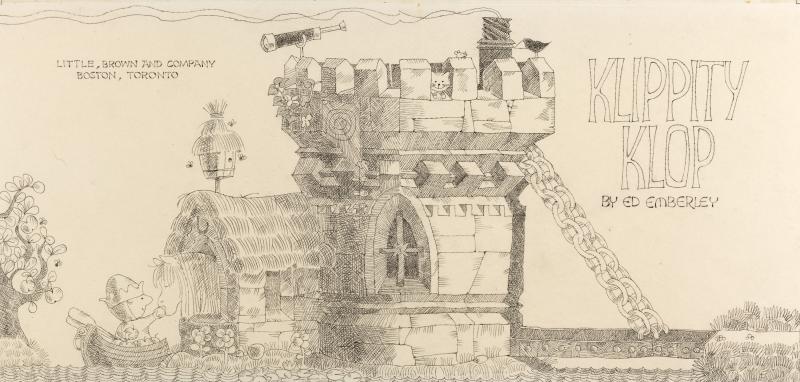

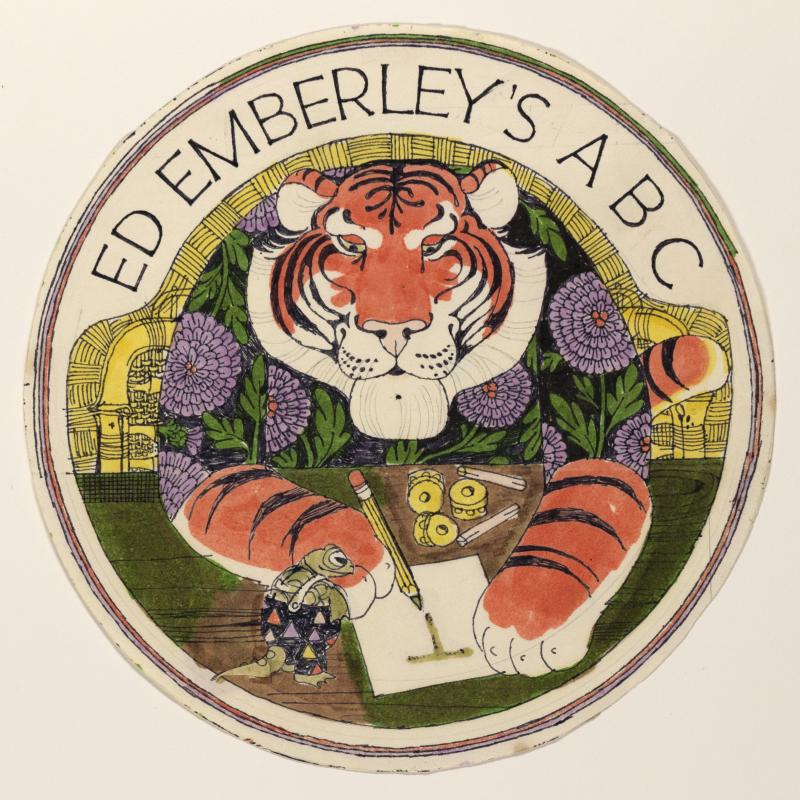

It was a rhythm that shaped Emberley’s approach to his career and his work. If a book sold well, his publisher would ask him for another in the same style, and he would oblige. The Drawing Book of Animals spawned Make a World, Drawing Book of Faces, and on and on. If the book didn’t sell, Emberley moved on to a new book with a new technique, look, and approach. While his drawing books were selling well, he made very different books with lovely line drawings (Klippity Klop and Krispin’s Fair), the stunning optical art masterpiece The Wizard of Op, and a magnificently illustrated version of a classic ABC book. Sometimes, he had to abandon a book he had made substantial progress on (Space City and Get Up and Shut the Door), which seems to have hurt him the most.

When a finished book came back from the publisher, along with a package of its production artwork, Emberley filed the material in a box on a rack in the studio and didn’t look back. The healthy thing for him to do, of course, was to keep his eyes looking forward to the next project, next book, next technique, and to keep a sense of work-life balance, even though he worked from home. Outside of Emberley’s studio, the house didn’t obviously belong to an artist or children’s book author. Copies of Emberley’s books occupied no particular place of pride. There are no framed artworks or photographs from his career, nor much in the way of artwork or books at all. The Caldecott Medal is kept in a drawer.

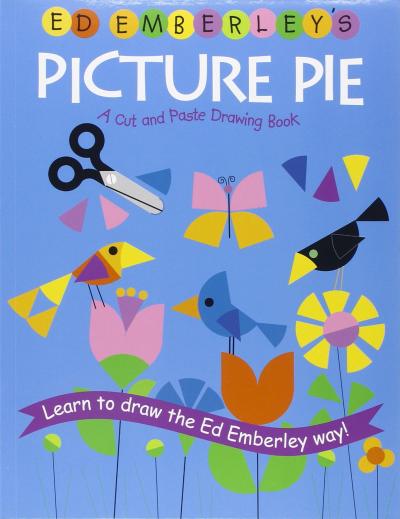

In the 1980s, Emberley undertook a project illustrating a set of computer literacy books by Seymour Simon. They’re hilariously outdated now—explaining terms like a cursor, mouse, and so on—but they demonstrate Emberley’s eagerness to learn and employ new ways of making books. Soon he was trying to complete entire books digitally, in fact, he had hoped to do so for his 1992 bestseller Go Away, Big Green Monster. He was ahead of the industry, but publishers and printers weren’t ready to go there yet, and if you’re old enough to have worked on computers in the early 1990s, you’ll understand! By 1996, for his second Picture Pie book, Emberley went entirely digital and didn’t look back.

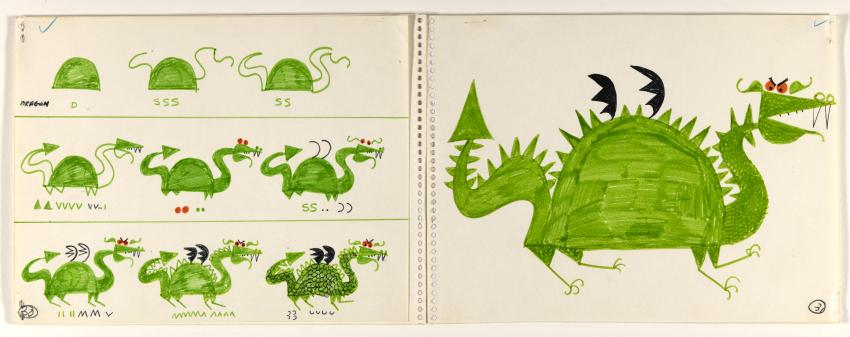

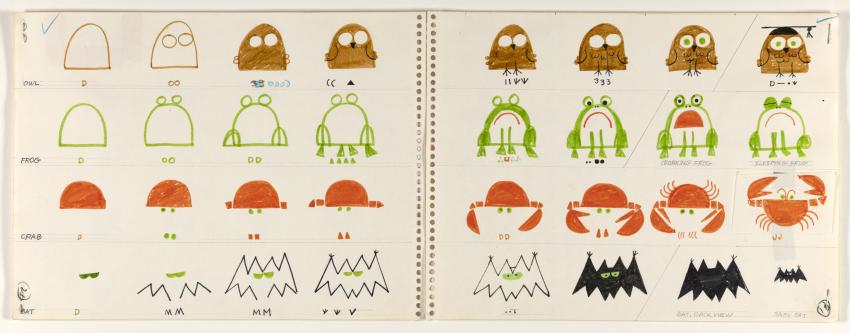

In many ways, Emberley’s drawing books are about knocking the concept of “Art” off its big perch. The books show ways to draw, not ways to be an artist. In fact, the words “art” or “artist” are nowhere to be found in the Drawing Book series, save for Emberley’s hand-lettered Library of Congress shelving notes in the colophon. When he gives talks for young people, Emberley likes to say that he “draws pictures for a living.” In his drawing books, he wasn’t out to spawn legions of artists, he wanted to give kids a tickle of fun and success at drawing something they might not have thought they could draw. “Not everyone needs to be an artist,” he says, “but everyone needs to feel good about themselves.” And it’s key to Emberley’s world view that one have fun drawing without the burdensome idea of being an “artist” —just as one can have fun playing catch or shooting baskets without thinking of one’s self as an athlete. Emberley constructs his images from patterned triangles, parallel lines, circles, dots and scribbles. “This kind of copying,” he smiles, “I shouldn’t tell you this, but this is the whole secret—this is an alphabet. We can write so easily because we have an alphabet with a small number of letters. Everything is made of that small number of letters. The same is true of imaging. If you can reduce things to a simple alphabet, then all you do is take those ‘letters’ and put them together.”

So why do so many schools fail to provide artistic instruction like they do with reading and writing? Why is it that when you ask a classroom full of six-year-olds to draw “wind,” their hands fly into motion, while if you ask the same class the same question six years later, all but two kids freeze? “Kids get swept away by their drawings,” says Emberley. “They’re there. They’re making a world, and if you encourage them, all kids are creative, at least until they go to school, where they are taught out of it by frowns from teachers and frowns from parents and frowns from their peers. Most children are at least as creative as adult artists until they get to first or second grade. Your job is to bring them back in.” It’s that role—gently telling kids to keep trying while managing to make it fun—that Emberley fills so brilliantly. Like landing a kickflip on a skateboard, putting a golf ball into a hole, mastering a video game level, memorizing a dance step, or any of the million other activities that bridge the mind and body, breaking an activity into tickles of fun and moments of success gives young people the enjoyment of being in their own bodies.

“It makes kids feel good,” Emberley explains, “The most important thing for me when I made a book is that you, the reader, would succeed, get a habit of success. And with success sometimes there’s a click. That ‘click’ that happens when you go as a kid from not knowing how to do something to knowing how to do something. Like riding a bike, you go from not knowing to knowing, and you can’t go back. I think that’s something that makes us human beings—you get that little electrochemical jolt that’s probably built into us, that little tiny eureka! And what I try to do with these books is take kids by the hand through that jolt—and it’s that breaking through that you suddenly start to crave. That’s the point, not to turn you into an artist, but to give you the habit of success.”